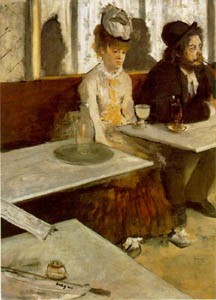

Painting by Edgar Degas

Liquid Dreams

Chasing Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, and other dead devotees in Barcelona’s bohemian barrio

By Taras Grescoe

IT DROVE BAUDELAIRE to Belgium, then to an early grave; it left Paul Verlaine a hollow-eyed wreck, wandering from bar to bar in Paris’ Latin Quarter accompanied by a misshapen shoeshine boy named Bibi-la-Purée. The deaths of Vincent Van Gogh, Oscar Wilde, and poet Alfred de Musset were hastened by their inordinate love for this poison, long since banned by the thinking men of all civilized nations.

Except, of course, in death-defying, devil-may-care Spain, where 136-proof absinthe is about as common as orange Fanta.

I’d come to Europe determined to uncork the liquid muse of the avant garde, the licorice-flavored, high-octane herbal alcohol popularized by a French doctor in 1792. I’d discovered that in the nation of his birth, absinthe’s sale had been strictly prohibited since World War I, but that in Spain, absinthe is considered just another aperitif, as familiar as vermouth and Campari. I’d found what the Spanish call Absenta in liquor stores in Madrid and in just about every bar in Catalonia; hell, I’d even found liter bottles of the stuff in the window of Can Canesa, the great grilled-sandwich shop in Barcelona’s Plaça Sant Jaume.

And now I was in Barcelona’s Barrio Chino–the infamous warren of narrow streets where Jean Genet set A Thief’s Journal and the Divine Dalí went slumming–finally face to face with my own glass of La Fée Verte, the 19th-century hallucinogen that, in its time, had ruined more lives than cocaine.

To tell the truth, I had been a little worried about my date with the Green Fairy. Before my trip, the only two people I’d met who’d actually tried absinthe–both mild-mannered Canadians–had gotten into fistfights after only a couple of glasses of the stuff. With this in mind, I’d chosen my drinking companions carefully: Mary, a Scottish painter who’d fallen in love with Barcelona in the ’80s and stayed on through the booming ’90s; and Henri, a gaunt Belgian pastrymaker with the sideburns of a rockabilly singer from Memphis. He’d left Ghent only two days before, using a Renault truck to transport 55-pound blocks of chocolate across France at a top speed of about 45 miles per hour, to fulfill his longtime dream of becoming the first trufflemaker for the sugar-loving citizens of Barcelona.

As drinking partners, Mary and Henri may not have been Sarah Bernhardt and Arthur Rimbaud, but they had forged their friendship over countless glasses of absinthe and knew its rituals. What’s more, under their tutelage, I was pretty sure that I wouldn’t finish the night in jail.

We had started the evening at midnight (this being Spain, after all) in the Bar Marsella, which, though recently purchased by two hefty Anglo-Saxons, has been preserved intact as a kind of monument to the fast-fading bohemia of the Barrio Chino. In the Marsella, yellowing posters for long-forgotten aperitifs curl on the walls, the paint peels suggestively, and half a dozen different tile patterns jockey for space on the undulating floor.

A young waiter had brought us small brandy glasses full of clear, oily-looking absinthe, along with all the attendant paraphernalia: a bottle of water, paper-wrapped lumps of sugar, and a three-tined trowel. In the classic version, one sets the trowel on the rim of the glass and slowly strains the water through the sugar cube into the absinthe until it dissolves. (Water wasn’t the only mixer for absinthe, however: singer Aristide Bruant drank it with red wine, and Edgar Allan Poe took his with brandy–and died, incidentally, at the age of 40 of a heart attack after a prolonged drinking binge.)

Mary introduces me to a local variation: I allow a sugar cube, squeezed between forefinger and thumb, to soak up the absinthe, which is 68 percent alcohol. Then, placing the cube on the trowel, I light it on fire until the alcohol burns off. After stirring the dissolving cube into the absinthe, I fill the glass three-quarters full with water, provoking a remarkable transformation. The liquid turns milky green–a color Oscar Wilde described as opaline, though to my eyes it looks more like a happy marriage of crème de menthe and whipped cream. In the murky half-light of the Bar Marsella, my glass of absinthe appears to be glowing from within.

I PAUSE before imbibing. Everything about absinthe, after all, is sinister. It proved the undoing of so many artists and writers that the best book on the subject–Barnaby Conrad III’s excellent 1995 work, Absinthe: History in a Bottle–eventually starts to read like an obituary page. It’s distilled from the grayish-green leaves of a shrub called wormwood–in Russia, the plant is ominously called chernobyl–and in large doses, its active ingredient, thujone, is a convulsive poison.

Even absinthe’s Greek name, apsinthion, means “undrinkable.” However, it was also one of the most popular aperitifs in fin-de-siècle France, the subject of a painting by Manet, a sculpture by Picasso, and innumerable anecdotes by Hemingway. A favorite among the women at Parisian bars such as the Nouvelle-Athènes and the Café du Rat Mort, absinthe even made it to the New World, where Mark Twain and Walt Whitman drank it in New Orleans’ Old Absinthe House. But the dead-eyed regard of actress Ellen Andrée, the barfly in Degas’ 1876 painting L’Absinthe, had always haunted me, and the more I look, the more the small groups huddled conspiratorially around the other tables at the Marsella resemble the doomed characters out of Emile Zola’s L’Assomoir.”

I imagine myself embarking on a long slide into debauchery, followed by months of hydrotherapy–a belle époque cure for alcoholics, which consisted of purges and a half-hourly soaking with cold water–in some Gothic asylum.

Suppressing a sensation of vertigo, I drink. And then I smile. Not at all bad–reminiscent of pastis, the licorice-flavored French aperitif, but with a slightly bitter undertone. Loosening up, I start trading anecdotes with my drinking companions about our worst debauches. The Belgian wins hands down–naturally–with his sad saga of three bottles of red wine, abrupt eviction from the restaurant where he’d consumed them, and his subsequent awakening to a curious sound: the slick hiss of car tires whipping past his ear in the gutter he’d chosen for his bed. Mary looks at the rapidly dwindling level of my glass and says with some concern: “You might want to slow down. This is brain-damage stuff.”

I, however, am eager to test Wilde’s description of absinthe’s effects: “After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second glass, you see things as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

In fact, as I finish my glass, the Bar Marsella is suddenly looking like the most wonderful place on God’s earth. When I walked in, I had been pretty sure that I was surrounded by nothing more than particularly hip backpackers, but suddenly the people at the next table begin to look strangely fascinating. They must be artists, I think to myself. And, as I work on another glass, the second phase of Wilde’s dictum begins to kick in: I start to see things as they aren’t. Isn’t that woman–the one with her arm around the red-headed guy with the goatee–staring at me through her half-lidded eyes?

My eyes, too, are playing tricks on me: When I focus on an ashtray or a beer spigot, the center of my field of vision becomes unusually clear, but the periphery looks watery, indistinct. Objects seem to be surrounded by yellowish haloes, as in a Van Gogh painting (the Dutch artist was on an absinthe bender for much of his career, including the binge in which he ran at Paul Gauguin with a razor and then cut off the tip of his own ear).

The overall effect is of wearing a pair of ill-fitting goggles in the bottom of a filthy–but surprisingly comfortable–aquarium.

However, remembering my Canadian friends’ warning about absinthe’s tendency to lead to fistfights–and noticing that the woman at the next table has somehow vaporized–I instead suggest to Mary and Henri that we take our custom elsewhere.

HENRI BEGS OFF, the combined effects of hard liquor and two days of driving with the French having taken their toll, but Mary and I continue our crawl through the Barrio Chino. Most of the rest of the madrugada (not surprisingly, the Spanish have a single word for the early hours of the morning) is a blur. We wander past the Franco-era prostitutes of Carrer d’en Robador, anarchist cafes, and the inevitable piles of street-corner refuse giving off fascinating, unidentifiable odors.

We stop at a nightclub called El Cangrejo, where a transvestite of the stature of the late Divine is performing beneath a sheep dog-sized wig. We poke our heads into the Bar Pastís, a temple of francophilia where the jukebox has been playing Edith Piaf since the ’40s; the London Bar, where people come to worship swinging England; and finally the Bar Kentucky, which is what an American tavern might look like if Antonio Gaudí was hired as a decorator. A barman who calls himself Pinocchio–he explains his sobriquet with a gesture to his bent nose–serves us our last absinthes of the night, and Mary and I ferry our drinks to the end of the mobile home-length bar.

As taxi drivers and prostitutes squeeze past us, we clink glasses, toasting what’s left of Barcelona’s rapidly gentrifying Barrio Chino. On this night, I won’t make it to Wilde’s ultimate phase of absinthism (it would take at least five more glasses), the one in which one’s surroundings reveal themselves in all their horror. In the Kentucky, on the contrary, the seediness continues to look glamorous.

I remember all those who had succumbed to the allure of the Green Fairy: among them, Toulouse-Lautrec, who carried absinthe around Montmartre cabarets in a hollow cane; and Alfred Jarry, the playwright who dyed his face and hands green, toted pistols on his absinthe binges, and died at the age of 34. With the opaline, nerve-damaging muse in hand, I drink to squandered talent and beautiful corpses.

But I’m really drinking to danger–and to the grateful realization that, in this world in which people are increasingly protected from themselves, there are still places left where we are free to choose our own poison.

Taras Grescoe has written for numerous publications, including ‘Wired,’ ‘Islands,’ ‘Saveur,’ the ‘Independent,’ and the ‘Times’ of London.

He lives in Montreal. This article first appeared on Salon.com.

From the June 14-20, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.