‘Drop City’ by T. Coraghessan Boyle.

Photograph by Pablo Campos

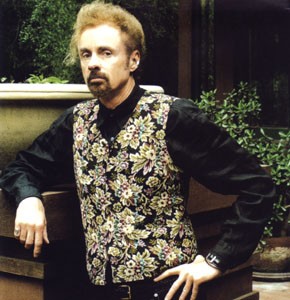

Under Fire: Commune-goers have had dramatic reactions against T. C. Boyle’s ‘Drop City,’ but Boyle reserves the right to fictionalize historical events.

Good Old Daze

Were Sonoma County communes better than T. C. Boyle’s ‘Drop City’ might have you believe?

By Gretchen Giles

What if you owned a clean, easy stretch of land encompassing hundreds of green acres, sweet-water creeks, plenty of fruit trees, fertile soil, and a clear road to town? You’d open it to every comer, no questions asked, and deny its use to no single person even if, say, 400 strangers ended up building 100 shacks upon it with no ready sanitation, electricity, or running water–wouldn’t you? Furthermore, if the legal fees to defend such extravagant personal benevolence ran into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, you’d still do it–right?

Nearly shocking to contemplate some 30 years later, that’s exactly what Occidental painter William Wheeler did in fact do. It cost him his inheritance, lost him 20 years of his artistic career, and he would never ever do it again. But was it fun?

“Oh, yeah,” he laughs with a thick drawl. Wheeler’s Ranch, as his 320 acres of hillside ocean view is known, and the nearby former community of Morning Star Ranch find themselves newly fictionalized in author T. Coraghessan Boyle’s 15th novel, Drop City. Boyle’s single, smaller 47-acre parcel Drop City exists near Occidental in the ether of the author’s mind as a commune of the unwashed and underemployed who, in 1970, drop out of society and onto the land of Norm Sender.

Adopting Morning Star owner Lou Gottlieb’s own motto–Land Access to Which Is Denied No One (LATWIDNO)–the fictional Sender tells Marco, a hitchhiker he’s picked up on the road from Bolinas, “You want to come to Drop City, you want to turn on, tune in, drop out, and just live there on the land doing your own thing, whether that’s milking the goats or working the kitchen or the garden or doing repairs or skewering mule deer or just staring at the sky in all your contentment–and I don’t care who you are–you’re welcome, hello, everybody. . . .”

And so into Norm’s welcoming arms come hippies from the Haight-Ashbury, cool-cat “spades” who do nothing but drink wine all day, stoners, freaks, bikers, draft dodgers, runaways, aimless travelers with no destination in mind–the whole stinking drug-addled panoply of a suburban mother’s Nixon-era nightmare. Human feces coil behind every rock, toddlers are casually dosed with acid, a teenaged girl is raped to mild community consternation, the brown-rice mush is endless, and the Man just won’t leave them alone, man.

When the bulldozers finally arrive with warrants to tear down the temporary shacks, Quonset huts, tree houses, and lean-tos that compose Drop City’s rural metropolis, the denizens crowd into a bus and head north to Alaska, where fattened salmon and abundant blueberries encourage them to wreak chemically enhanced havoc upon the Promised Land and themselves. The book’s focus then shifts to Boyle’s imaginary town of Boynton, Alaska, and the steaming morass of Sonoma County’s Drop City is left far–and untidily–behind.

Ah, fiction. Were it only so simple. Were it only so crude.

Were it only just fiction.

Just the Facts

Writers are a treacherous lot, and the admonition to write about what you know often results in a print depiction of a real Molly transformed into a fictional Polly. Novelists’ family members grow gradually resigned to seeing that their relative’s latest work is more a veiled piece of intimate history than a work of imagination.

Boyle hardly bothers with the veil. Drop City was the name of a real commune in Colorado, and its North Bay location is an amalgam of Wheeler’s Ranch and Morning Star. He takes the interviewer’s loophole when asked if it’s merely a coincidence that the fictional Drop City patriarch Norm Sender’s surname is the same as Morning Star cofounder and actual person Ramon Sender’s.

“It’s more of a metaphoric choice than others,” Boyle assures by phone from his Santa Barbara home. He says that he’s spent “many summers up on the Russian River” and in fact hopes to spend a good, long, hot stretch of this coming summer here. Furthermore, Drop City is not the first work he’s set in this area. Budding Prospects, his third novel, is placed in the marijuana economy of Willits in Mendocino County.

But he doesn’t rely solely on outside inspiration. One of the novel’s two couples, Pan and Starr, hail from Peekskill, N.Y., as does Boyle. And he supplies the delicious–to hard-core fans–device of not only reintroducing his imaginary Alaskan town of Boynton, but of having his other couple, Pam and Suss, meet there in a kind of high-north wife auction, as in “Termination Dust,” the lead short story in his latest collection, After the Plague.

Drop City North, as the Boynton enclave is known, is founded just before the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, in the last year allowing for that good old-fashioned homesteading, which is no longer legal. In an interview with the Columbus, Ohio, paper ThisWeek, Boyle mused, “You know, it’s just remarkable that such a thing ended in our time.”

What is perhaps as equally remarkable is that one generation of people was there to witness, participate in, and explode nearly every societal norm of the mid-20th century in just a few short years.

The Sweet Life: Sonoma County commune gurus Bill Wheeler (left) and Lou Gottlieb in a former incarnation.

Recent History

According to Ramon Sender, who is a composer and author as well as the administrator of the Noe Valley Ministry, the Virgin herself prompted the naming and founding of Morning Star Ranch. Lou Gottlieb, who died in 1996 and whom Sender describes as the “the standup bass funny guy” of the folk group the Limeliters, bought Morning Star from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s great-grandson, the poet John Beecher.

Beecher was a devout Catholic who lent the land for religious retreats, and the monks one day put all the many names of the Virgin into a bowl, intending to pull one out to name the land. Morning Star was the random pick, and Sender avers that the presence of the Virgin has informed the place ever since. He moved up there in the “apple blossom time of ’66.” By summer, Gottlieb and six others had joined him.

“What if you owned a piece of land and it suddenly became Lourdes?” Sender asks rhetorically. “How do you stem the flow, how do you deal with it?”

Sender himself tried to deal with it by posting such rules as “yoga at 8am, meditation at 9,” only to be laughably ignored by the growing procession of people who, alerted to Morning Star’s newly established community by the San Francisco-based group the Diggers, a coalition devoted to making food and housing free to everyone, began arriving each day on Gottlieb’s land.

“That whole summer of ’67 came down on us and it became obvious that it was going to be hard to control the flow of people,” Sender remembers. Gottlieb paid over $15,000 in fines (and that’s 1960s dollars) defending his right to welcome all comers, depleted his Limeliter royalties, and devoted almost more time to court appearances than idling away sunny afternoons in his orchard, including losing his bid to tithe the place to God. As the commune grew, sheriffs and health and building inspectors became as ubiquitous at Morning Star as the hippies themselves.

“We had some families with kids, but the environment became less and less conducive, especially because of the police, and the toilet situation was just out of control,” Sender says. “On that level, perhaps exaggerated by Boyle, he had a point.”

With county officials increasing their pressure on the Morning Star community, Bill Wheeler found himself called into history, stepping in to open his land when Morning Star faltered. “The reason that I did that was because I felt that it was the spirit of my generation, and I could not turn my back on what was happening, even though it created a certain amount of vulnerability for me,” he says by cell phone from his ranch, where he continues to live off the grid.

“The open-land movement was an aberration of those years and the Vietnam War and the craziness of our society back then,” Wheeler continues. “It was just crazy, there’s no way that it could continue to manifest itself. It worked in those days because there were so many people who were idealistic and loving, but there is so much criminality now that it would outweigh any kind of idealism and it would be impossible to do what we did back then now.

“But it was a lot of fun, and what was important to us was that there was a lot of art, there was a lot of music, and there was a lot of creativity.”

Musician and author Alicia Bay Laurel was among those whose youth, creativity, and idealism led her to Wheeler Ranch. Arriving as an established working ceramicist at age 19, Laurel blesses Wheeler for teaching her to garden, a skill that figures mightily in her hand-written and hand-drawn bestselling 1971 book, Living on the Earth.

Featured in the March 9 issue of the New York Times Magazine, updated for Y2K, and poised to be reissued this fall by Gibbs Smith publishers, Living on the Earth was written, Laurel says from her Hawaiian home, “because there was so much we didn’t know. Some of the things I learned from Wheeler Ranch, and some of it I learned at the public library. I felt that people should know how to garden, how to make our clothes.

“Most of us had just walked out of a life living in the city,” Laurel adds. “What we were was an outdoor crash pad, and a lot of us knew zip about living outdoors and zip about having babies without a hospital. There were a lot of mistakes of that kind.”

Drop Reading

Neither Wheeler nor Laurel has read Drop City, but Sender most emphatically has. As the editor of the online Home Free Home, a nonfiction history of the Morning Star and Wheeler ranches, and as the host of the MOST Post, an online forum for those communes’ alumni, he is nonplussed.

“I just had to push myself to finish the book,” he says. “I didn’t find any of the characters to be developed with depth; I thought that they were very flat in a kind of Zap Comic-y type of way. Furthermore, I didn’t recognize anyone I knew. I felt that Boyle took a couple of tragic incidents that occurred and kind of threw them all in to portray the worst of the times.”

In Drop City, a horse is fatally mauled in an auto accident, and one of the resident’s children almost drowns in the greasy muck of the swimming pool. In reality, a horse tethered near the temporary Marin commune of Olompali did escape to be killed on Highway 101, and a child tragically died there when who-knows-who wasn’t paying enough attention.

Boyle, who has corresponded with Sender about these complaints and who recently addressed his reservations live on the KQED 88.5 FM call-in show Forum, remains available to discuss such concerns but steadfastly defends his depiction.

“I’m not political, I’m not trying to dis communes,” he told Sender. “I’m just a fiction writer. As a free agent in society, I’m allowed to reflect on things in society which may not be the way that others do.”

Reminded of this radio exchange, Boyle reflects, “One of the nice things [about his recent book tour] was to be in contact with Ramon and others from the movement. My intention was not to glorify or vilify or even reminisce about it. I’m not writing a history of communes; I’m writing a piece of fiction for my own purposes.”

Boyle, who says that his research for Drop City stemmed almost entirely from Richard Fairfield’s 1972 book, Communes USA, agrees that “the whole concept of going back to the land and not being caught up in consumer society was good. I regret the passing of that. The Bay Area, with its dotcomdom and yuppiedom has become particularly bereft. In this overpopulated world, I don’t think that it’s possible to ever drop out in that way again.”

Boyle says that the main criticisms of his novel have been that it is either not sociological enough or that he focused too broadly on the negative. He dismisses the first complaint with the reminder that it’s fiction and addresses the latter by saying flatly, “I didn’t focus on the negative. In fact, I think that the book in the end becomes a celebration of community. I didn’t plan it that way; it’s just the way it came out.

“[Conflict] makes for a better story, it makes it more interesting. If everyone is perfectly content, it makes for a kind of dull read. In George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, when [protagonist] Jack Tanner goes to heaven, he realizes that it’s utterly boring.”

It Takes a Village

As with Morning Star, authorities also shut down Wheeler’s Ranch. With its 100 outbuildings bulldozed and burned in 1973, the commune closed. Wheeler’s daughter–born Raspberry Sundown Hummingbird, a name she shed in adolescence for the more practical Jessica–was one of eight babies born there.

The commune had been featured in the July 7, 1967, issue of Time magazine and its demise shown on the evening news. Walter Cronkite shook his head over the images of the downed, flaming buildings and proclaimed it “a damned shame.” Wheeler’s fortune, derived from a great-grandfather’s invention of a type of sewing machine, was shot.

Less dramatically, Boyle leaves his characters in their commune on Christmas night in Alaska. They still have six full months of dark and cold to endure, and their future is unclear. “The ending invites you the reader to supply the events,” he says. “Will Norm [who has decamped with his girlfriend] come back the following summer? Who are the people who belong, and who doesn’t? If I had written another hundred pages, it would just be more of the same. It could be another thousand pages, but for my purposes, the artistic vision that I had is complete.

“All of my historical novels have a coda that bring you up to date on the characters; in this one, I thought it would be detrimental.”

Detrimental, perhaps, because all of us can look back down the winding narrow tube of 30 years and see how it all turned out. The sixties, some posit, blew all of the rules apart but didn’t replace them with anything.

Sender is more pragmatic. “Whatever the hippies discovered, we are now the beneficiaries of. Health food, the ecology movement, the Green Party–so much of what was discovered then has become part of the mainstream culture now,” he says. “Certainly, much of it has been co-opted, changed, and corrupted, but the impulse to nurture Mother Earth, to return to her, and to reinvoke the tribal remain.

“Although we’re going through a kind of a strange time now, I hope that it’s a last hurrah of a fundamentalist right-wing orthodox wave of things. Maybe out of this,” he says hopefully, “will come a whole new movement of people.”

Bill Wheeler is content to exhibit his plein air landscapes at San Francisco’s George Krevsky Gallery, live peacefully, and throw his annual May Day party, when the ranch again becomes a place of communal gathering. “When it came to an end, it came to an end, so be it,” he says philosophically. “I still think that community is the healthiest way to live, because people take care of each other and there’s less crime and mental illness and the alienation that people feel.”

Alicia Bay Laurel becomes almost dreamy when asked if it was all worth it. “I don’t know if the word is nostalgic or if the word is envious, but I could do it,” she says, “all over again.”

From the May 15-21, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.