An earthworm moves through the soil with its mouth agape like a whale gulping seawater for krill. But instead of tiny crustaceans, the toothless worm eats microorganisms and bits of dirt, leaves and food waste.

That’s where things start to get interesting.

Once those microorganisms enter the worm’s gut, they meet an even greater number of micro flora, and create an exponentially greater number of micronutrients. Garbage may go in, but it’s not garbage that comes out. It’s black gold for soil health and farmers who want to boost the vitality of their crops.

And it’s gold for Sonoma worm farmer Jack Chambers.

After a career as a commercial airline pilot, peering out the cockpit with the world rushing by 30,000 feet below, Chambers now lives life much closer to the ground. He became an avid gardener and 23 years ago that interest took him even deeper into soil under his feet.

“I had a big garden in town and a friend said I should come out and see the worm farm,” he said. “I came out a bought a five-gallon bucket of worms and I took it and put it into my compost pile. I went on a five-day trip and a when I got back the compost pile had been transformed by these worms.”

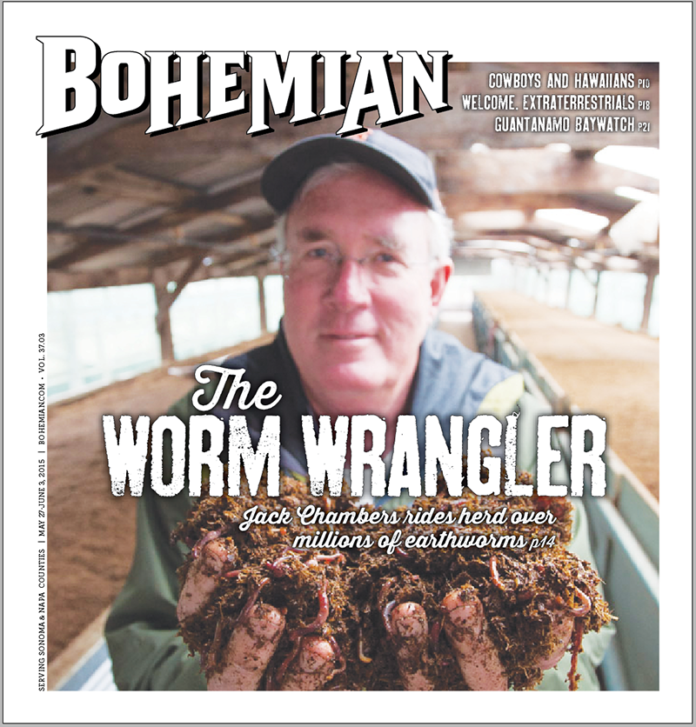

Chambers, 62, is an affable man with a bemused expression and a deliberate manner of speaking. As he says the word “transformed” he waves his hands as if he were performing some kind of sleight of hand. Two decades in, he still regards worms with wonder. He was so impressed by the transformation of his compost pile that he came back to the farm and asked the elderly owner if he could work with him. A few months later he asked if he could buy the place.

“Two weeks later he said yes and three days later we sold our house and we had a worm farm.”

At Sonoma Valley Worm Farm, Chambers raises worms by the millions. But unlike raising cattle for beef, he husbands the worms for what they leave behind: castings, better known as worm poop.

When raising chickens or cattle, what you feed the animals goes a long way to dictate the quality of the final product. It’s the same with worms. There are about 10,000 species of earthworms, but only four in the U.S. are suitable for vermiculture. The worm of choice is Eisenia fetida, known to savvy farmers and trout fishermen everywhere as the red wiggler.

The red wiggler is particularly suited to vermiculture because unlike other earthworms, they live close to the surface and eat decaying organic material like cow manure, leaves and food scraps. They’re nature’s decomposers. Turn over a rock or a bucket that’s been sitting outside for some time and you’ll probably find a few red wigglers in the soil. Red wigglers also don’t mind being crowded. When food is abundant they live and reproduce in dense masses of squirming worminess. Rapid reproduction is helped by the fact that the worms are hermaphroditic so they don’t spend much time looking for a mate.

“Once you get bit by it and have the worms and see what they do—” says Chambers. “I love them but people are either with you or they’re not.”

He tells the story of a vineyard manager who got grossed out when Chambers reached into a worm bed to show him a fistful of his writhing beauties. Others dig right in with him to hold a handful for themselves.

Chambers is motivated by a desire to move away from so-called “conventional agriculture,” a practice he says is better called “chemical farming” because of the many synthetic inputs it requires. But people are finding that method of agriculture doesn’t work so well over the long term, he says. Worms, he believes, can be part of the solution.

“It’s all about food, actually. It’s helping people grow better food. It’s a think-globally-act-locally kind of deal.”

Chambers gets praise from farmers and vermiculture experts alike for the quality and consistency of his product. Cannabis growers also like his stuff.

“He’s one of the more advanced operators in the industry,” says Rhonda Sherman, extension advisor at North Carolina State University and an internationally known worm expert. She founded the university’s annual conference on large-scale vermicomposting, the only gathering of its kind. “He’s not just slapping this stuff together.”

Chambers trucks in organic dairy manure mixed with straw from West County farms and composts it in steamy piles that reach temperature of 140 degrees or more. Composting kills pathogens and weeds and leaves the manure smelling sweet and earthy. It’s also irresistible to the millions of worms living in the dozen 130-foot-long beds nearby.

Red worms eat nearly three times their body weigh each week. Chambers and his crews sprinkle a layer of the compost on of the beds and the worms worm their way up to eat it and turn the reddish-brown compost black.

That’s what Chambers and his customers are after—worm compost.

In a device of Chambers’ own design, a breaker bar sweeps under the beds to shave off a layer of the material, which has the consistency of fine coffee grinds. The stuff is then sifted and bagged. Farmers, mainly winegrowers at nearby wineries, anxiously seek it out. He produces about 2,000 yards of worm compost each year.

“All of our material is spoken for,” he says. “Demand is ahead of supply.”

While worm castings add fertility to the soil in the form of nitrogen, its real value is the boost in vitality it gives to crops.

“There is something special going on inside the worms,” says Sherman. “What comes out the other end is teeming with microorganisms. The beauty of vermicompost is it has plant hormones. They have a real effect on seedling emergence and plant growth.”

Worm compost helps suppress plant diseases and pests and produce crops with higher yields, she says.

As far as farming goes, the worms do most of the work as long as they stay fed and comfortable. They are a hearty worm, but sensitive to temperature extremes. In the summer when temperatures reach 100 degrees, Chambers says the worms climb on top of their beds to cool off en masse. They emit an eerie sound like a million faintly smacking lips.

“It is important to realize the power of nature,” says Chambers. “It’s so simple but it’s so complex. If you can mimic and help that along that’s what we’re trying to do. Feed the soil and let the soil feed the plants. That’s what we’re all about.”