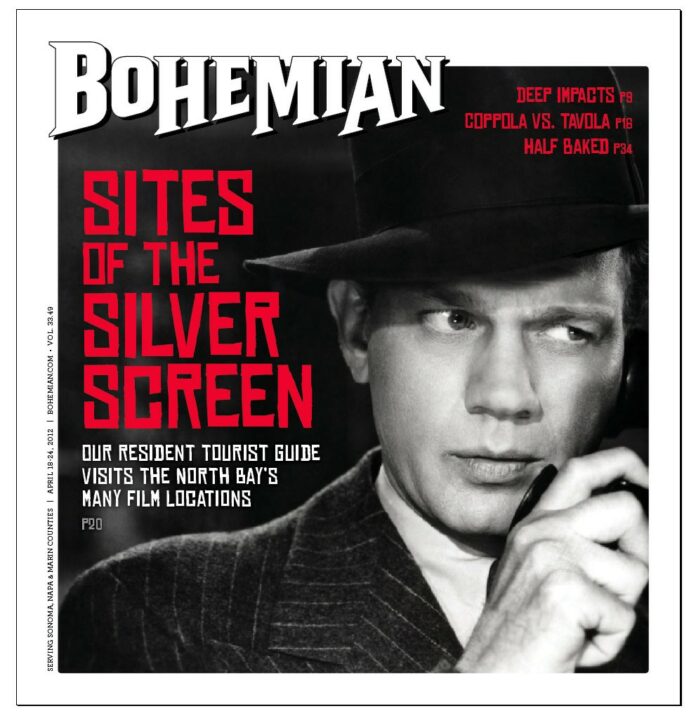

We in the North Bay love visiting historic sites. Not just important locations in classroom history, either. We like to drive by a place and say things like “That’s where Lance Armstrong ate when he was in town,” “Barbra Streisand stayed at this hotel in the 1970s,” and—perhaps with a tone of caution—”These are the mountain bike trails once rode upon by George W. Bush.”

And there’s no local quip like a movie-related local quip.

The North Bay has had an up-and-down relationship with Hollywood filmmaking, from Hitchcock’s The Birds and Shadow of a Doubt and the presence of icons like Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas to one of the biggest Hollywood battles in local history.

Scream, the 1996 Wes Craven horror film that went on to make $173 million at the box office, was originally set to be filmed at Santa Rosa High School. But parents were worried about glorifying violence on a school campus, and after months of the school board delaying filming, Craven was forced to film in Sonoma instead and kill off his big star, Drew Barrymore, within the first 12 minutes of the movie. He famously retaliated in the film’s closing credits: “No thanks whatsoever to the Santa Rosa City School District Governing Board.”

The controversy was not without precedent. One rallying cry among concerned parents around the Scream brouhaha was “We don’t want another Smile, do we?” Smile, a brilliant satire of small-town beauty pageants, was also filmed and set in Santa Rosa in 1975. But the film’s irreverent skewering hit a little too close to home for residents, whose excitement turned to scorn upon its release.

Since, we’ve been a too-cautious bunch toward Hollywood, and vice-versa. Five years after the Scream debacle, when the Coen brothers made The Man Who Wasn’t There—their declared homage to Shadow of a Doubt—they set the story in Santa Rosa but tellingly filmed it elsewhere, in Orange County. Just this month, George Lucas bitterly shelved plans to build a movie studio in Marin over protests by homeowners in nearby upscale Lucas Valley Estates, and vowed instead to sell the land for low-income housing.

Still, there’s nothing like watching a movie and then visiting the places where it was filmed. Our resident tourist guide this year is meant to inspire day trips to those very movie locations, and we’ve included directions and street addresses to the more un-Googleable spots. (Please, do not disturb private residences.)

There are dozens of films we coudn’t fit here—Bottle Shock, Phenomenon, A Walk in the Clouds, All My Sons, Inventing the Abbots, Impact, Happy Land and so many more. But we’ve also tried to dig a little deeper beyond the usual suspects of locally shot films, and hope you’ll learn more about Hollywood history in the North Bay.

Aaaaaaannnnd—action!

‘Shadow of a Doubt’

The ultimate Santa Rosa movie, Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Shadow of a Doubt’ (1946) contains vivid scenery and small-town charm galore. Hitchcock himself called it his favorite of his films, and though Joseph Cotten and Teresa Wright are the film’s top two stars, third billing would have to go to 1940s Santa Rosa itself for providing a perfect setting of quaint innocence for the story’s sinister undercurrent.

Cotten’s dark nature is foreshadowed as his train pulls into the Santa Rosa train station, emitting a huge cloud of black smoke—a pure Hitchcock touch. The depot is still there today at Fourth and Wilson, as is the Western Hotel, seen in the background (it’s now Flying Goat Coffee), and Hotel La Rose.

The Shadow of a Doubt house is at 904 McDonald Ave., and it’s instantly recognizable from the front. The wrap-around porch, the wrought-iron railing above the porch roof, the split walkway—it’s all there. The scenes “inside” the house were filmed on a Los Angeles set, and the back-door exterior staircase was also a set construction. But walk around on Fourteenth Street and you’ll find the garage, the site of a terrifying scene late in the film. (The original double doors, important to the action, have been upgraded.)

Sadly, almost all of Santa Rosa’s downtown today is unrecognizable from the film. The towering courthouse was torn down in 1966. The ivy-covered Carnegie library, where young Charlie asks for a newspaper late at night, was demolished in 1964. The American Trust building where Uncle Charlie makes a deposit, also gone, and the Tower Theater, where young Charlie runs into some friends, torn down. The Til-Two bar, once at the southwest corner of Third and Santa Rosa Avenue, is an empty commercial building. The white church at the close of the film is now a concrete parking garage.

However, a few features remain. Scenes of a policeman directing traffic on Fourth Street show the Empire Building and its still-working clock tower. On her way to the library, young Charlie walks by Arrigoni’s Market, on Fourth and D—squint and you can see the sign—which is still there. The Rosenberg Building at Fourth and Mendocino is still the same, now home to Pete Mogannam’s Fourth Street Market. And when Uncle Charlie leaves Santa Rosa, in the background is a vaguely Spanish-style building, which still stands as Chevy’s restaurant.

Since it release, Shadow of a Doubt has given generations of Santa Rosans a new appreciation of their city. But during the funeral scene at the film’s end, it’s hard not to feel an extra eulogy for the city depicted in the movie—the Santa Rosa that once was.—Gabe Meline

‘Smile’

When director Michael Ritchie included a scene filmed at Santa Rosa’s Howarth Park in the 1972 Robert Redford vehicle The Candidate, he took note of the city as a perfect backdrop for small-town dysfunction. A few years later, in 1975, ‘Smile’ took advantage of the all-American town gone awry: the cops are horny, the parents are drunk and Santa Rosa is a barren wasteland. Locals hated Smile upon its release, but there’s a lot to love in the film’s very funny, insightful skewering of young-miss beauty pageants, with performances by Bruce Dern and, in an early role as a beauty contestant, Melanie Griffith. Anyone who lives in Santa Rosa should seek it out.

Watch for the opening montage with scenes of Highway 101, Coddingtown, Denny’s and the Journey’s End mobile home park. Most of the film is shot at the Veterans Memorial Building on Maple Avenue, across from the fairgrounds, where all the beauty-pageant action takes place. Certain scenes were filmed on Stevenson Street, behind the Vets Building.

Bruce Dern’s car lot is on Corby Avenue (you can see the Chevrolet sign in the background), and at one point he takes his son to Community Hospital on Chanate Road. There’s also a bizarre fraternal-club initiation in Howarth Park, which is changed to “Ripley Park” in the film.

The line that always has residents howling in theaters—on the rare occasion that the film is screened locally—comes when a boy trying to buy film discovers the camera shop doesn’t have it in stock. He turns away from the counter, and mutters, “Santa Rosa sucks.” The camera shop’s location was part of the 12 square blocks that were razed to build the Santa Rosa Plaza, and is no longer there. It calls to mind another line in the film: “Santa Rosa is so beautiful,” says a blank-eyed, perpetually smiling pageant contestant. “I mean, I thought the shopping mall in Anaheim was great, until I saw yours!”—Gabe Meline

‘Smooth Talk’

A disturbing coming-of-age drama, ‘Smooth Talk’ stars Laura Dern as a bored yet sexually aroused 15-year-old, and Treat Williams as a smooth-talking sexual predator—and was filmed, in 1985, largely at a Sebastopol Victorian home and two shopping malls in Santa Rosa. In the movie, the vintage home at 2074 Pleasant Hill Road where Connie and her family live is being painted white by Connie’s mother (Mary Kay Place).

Today, the house is pink and can be seen from the road through the filter of the same apple trees, but now boasts a renovated front porch, landscaped flower gardens and a paved driveway. The current owners who moved there in 1995 recall being told about the movie by local apple farm workers, who said the house was chosen because it was so run-down.

For fun, Connie and her friends go shopping at Santa Rosa Plaza, in downtown Santa Rosa, and are dropped off in front of the now-defunct Mervyn’s (now it’s Forever 21). Inside, the girls come down the escalator with Macy’s visible in the background, but then a strange change occurs that only locals would notice—they’re suddenly in the Coddingtown Mall instead. They follow some guys into a clothing store, currently the location of Work World Clothing, inside the mall across from Macy’s. And later that night, Connie gets stranded in the mall parking lot, lit by the neon of the old JC Penney’s sign.—Suzanne Daly

‘Storm Center’

For decades, those enamored of Shadow of a Doubt have long missed the opportunity to see another black-and-white film shot on location in Santa Rosa: ‘Storm Center’ (1956), starring the great Bette Davis. In it, Davis plays a librarian who refuses to remove a book, The Communist Dream, from the downtown library. She is fired by the city council and her alleged red ties are scapegoated to advance the campaign of a local politician. The film had been unavailable on VHS, and then DVD, for years. In 2010, Sony finally released a master on DVD.

That may be because it’s not a very good film. It tries and ultimately fails to make an emotional connection, although it deserves credit as the first movie out of Hollywood to bravely take McCarthyism head on. Not only is Davis’ character scorned in the film, but according to Turner Classic Movies, “during the shooting of the film in Santa Rosa, local women’s groups harassed Davis with letters warning her of the film’s dangerously subversive content.” Davis didn’t land a major feature role for another five years.

Storm Center takes place mostly at the beautiful old Carnegie library on Fourth and E, where only a cornerstone remains—it was torn down in 1964. There’s a town meeting at a recognizable hall that’s now the Masonic Lodge on Seventh and Beaver, and quick scenes in front of the old courthouse, now torn down. Watch for a scene where Davis is chatting with local children—she walks down the 700 block of Fourth Street, and you can make out the storefronts of what used to be Sawyer’s News and the Last Record Store (it’s now Simply Chic).

Businessmen and city workers conduct casual business in a restaurant, Morrissey’s, which no longer exists. Local resident Steve Shirrell, whose parents were extras in Storm Center, says later scenes inside a bar were filmed at the old Santa Rosa Golf & Country Club off Highway 12 near Los Alamos Road. The movie is so dear to Shirrell—”the old library scenes are just precious,” he says—that he’s donated a copy of the film to Video Droid in Santa Rosa. Shirrell’s brother Robert notes that even though Storm Center‘s theme was serious, the mood on the set among the extras was convivial. During filming of the terrifying final fire, “mom got a little too drunk and was laughing,” he says, laughing himself, “and the director had to cut the scene.”—Gabe Meline

[page]

‘Stop or My Mom Will Shoot’

If you’ve ever wanted to see Sylvester Stallone in nothing but a dress shirt and giant cloth diaper, ‘Stop or My Mom Will Shoot’ is for you. If you’re a Sonoma County resident and you find that mental image more confusingly horrific than Justin Bieber fathering a child, there’s another reason to watch this D-grade classic: it was filmed at the Santa Rosa Air Center.

Posing as the Brunswick Air Strip, this one-hanger landing field off Wright Road sets the film’s climactic showdown, in which Stallone chases a cargo plane down the runway in a detached semi. He finally grounds the plane, but things look bleak until his frail mother (Estelle Getty) saves the day with a stolen gun, a wicker handbag and the line “Nobody hurts my baby!”

The final scenes of Stop or My Mom Will Shoot were shot over a period of several weeks, though by the film’s 1992 release, the small airport had closed. It was built in the early ’40s as a Naval auxiliary landing field where fighters, bombers and torpedo pilots were trained, and transitioned to a civilian airport in the mid-’60s, eventually ceasing operations in ’91. It’s now an empty field, with some barracks doubling as artist studios, near Wright Road at Finley Avenue.

Of course, if panoramic sweeps of the Santa Rosa hills shot from a speeding semi aren’t your thing, this cult flick is a treasure trove of other Stallonian nuggets. You can listen to him refer to love as “the feeling stuff.” You can revel in the classic wit of lines like “I give you an inch and you take an entire New Jersey turnpike.” You can watch him shake a terrier named Pixie. And there’s always that diaper—complete with a giant safety pin and strategically draped flap—that will haunt you for the rest of your days.—Rachel Dovey

‘True Crime’

Seen from a ferry boat on San Francisco Bay and beautifully lit by the setting sun, the view of San Quentin prison makes one wonder at the value of this astounding piece of Marin County property. Thus opens ‘True Crime,‘ a 1999 murder mystery set in the greater Bay Area, which focuses on a San Quentin death-row murder case. Produced and directed by Clint Eastwood, the film follows the downward arc of Steve Everett (Eastwood), a has-been Oakland Tribune journalist and serial womanizer.

Viewers find a 69-year-old Everett at Petaluma’s Washoe House (2840 Stony Point Road), trying to work his magic on a 23-year-old co-worker, Michelle (Mary McCormack). An exterior shot of the 1859 roadhouse appears to be taken from across the street, the neon sign rosily glowing through the rain and fog. Inside, Everett and Michelle are enjoying drinks, sitting at the far end of the brightly lit bar, which in reality is quite dim. You can park your buns in the same seat as Clint; just turn the corner of the bar so you’re seated facing the door. In the movie, a white Stroh’s sign hangs over the door; it’s now replaced with a green and white Beck’s sign.

Everett, unsuccessfully making a pass at Michelle, watches her weave her way out the door to her car, illegal in today’s world. Michelle turns right onto Roblar Road, guns the engine while playing with the radio and crashes on “Dead Man’s Curve,” a non-existent feature of this road. After Michelle’s death, Everett picks up the case she was working on, and returns to the Washoe House.

The hundreds of dollars pinned to the ceiling are unchanged since the movie’s filming, according to waitress Addie Clementino, who has worked there for 29 years. Clementino adds that Eastwood found the location when he stopped in one day with a few of his Bohemian Grove friends. Although she waited on Eastwood during subsequent visits, Clementino and the staff weren’t allowed to work during filming. They were, however, paid for their time off.—Suzanne Daly

‘Scream’

This horror classic is a treasure chest of local scenery, but due to conservative concerns over the violent nature of the film, as mentioned, ‘Scream’ (1996) couldn’t be filmed at Santa Rosa High School. Its replacement as the film’s Woodsboro High was the Sonoma Community Center at 276 E. Napa St. in Sonoma, still standing and looking exactly the same. Interestingly, in Craven’s cameo scene as a janitor, there’s a hanging banner in the hall reading “Panthers,” the mascot for Santa Rosa High School. Other hallway scenes were filmed at the abandoned Yeager & Kirk lumberyard on Santa Rosa Avenue, now demolished.

Many scenes of Woodsboro were filmed in Healdsburg, especially in the Healdsburg Plaza, right downtown, and in front of buildings on Center Street. The Woodsboro police station was the old Healdsburg police station at Center and Matheson, which is now Oakville Grocery and looks completely different. The grocery store scene was filmed at Pacific Market, on Town & Country Drive in Santa Rosa, still there and largely the same. And the video store scene was filmed at Bradley Video, in the shopping center at 3080 Marlow Road, which is now closed.

Scenes at Tatum and Dewey’s house were filmed at 824 McDonald Ave. in Santa Rosa, which is the most accessible Scream house to view from the street—you can still see the wraparound porch where Neve Campbell sat in the film. Casey’s house, where Drew Barrymore is killed, is on Sonoma Mountain Road in Glen Ellen near Enterprise Road, but it’s gated and set far back from the road. Sidney’s house is at 1820 Calistoga Road, but it, too, is set off from the road and has been remodeled since the film. The final party-scene house is in Tomales, at the very end of a long driveway marked 3871 Tomales-Petaluma Road. Caution: it’s a private drive.—Gabe Meline

‘Mumford’

The 1999 film ‘Mumford’ begins with an old-timey shot of Tomales and the voiced-over line “I got out of the truck in this two-bit town.” But though the idyllic, fictional town of the movie’s title is actually a mashup of nearly every Sonoma County city, the West Marin hamlet isn’t among them. Instead, Tomales forms the backdrop to a minor character’s twisted fantasies, filled with obliging landladies, their even more obliging teenage daughters and nurses who know tricks “they didn’t teach in nursing school.”

Out of creepdom and in Mumford’s “real” setting, a variety of local landmarks can be spied by the watchful resident eye. The main character, a supposed therapist also named Mumford (Loren Dean), and his friend/client, techy wunderkind Skip Skipperton (Jason Lee), sit down for a drink at Old Main Street Saloon in Sebastopol. Mumford goes home to a Petaluma house, eats lunch in Healdsburg, visits a client in Sonoma and routinely hikes up to vantage point overlooking his piecemeal town in Calistoga. Analy High School was used for several scenes in the film, as well.

Dave Wiseman, now a manager at Video Droid, was an extra in the film. You can see him sitting in an alley next to Zooey Deschanel’s character in a montage scene near the end of Mumford, wearing a generic shirt (he’d worn one with his band logo on it, to hopefully show it off in the film but was told he had to change). The alley that they’re sitting in connects Kentucky and Keller streets in Petaluma, by the Phoenix Theater. In addition to getting $50 for his day of work, he and his friends were given free packs of cigarettes. Deschanel played a chain-smoking, magazine-obsessed high schooler, but in reality, the wide-eyed actress didn’t smoke, and she looked unnatural with her cigarettes, Wiseman recalls, so the director told her to watch and learn from the cast of local extras.

Wiseman had another interaction with the now-well-known actress: he asked her out on a date. “She politely said she was too busy,” he recalls. “But I asked. She’s super-famous now, but she wasn’t at the time. For years, every time she’d be in a movie, I’d get more excited, because more people would know who she was when I told the story.”—Rachel Dovey

‘Thieves’ Highway’

Before he was exiled to France on a Hollywood blacklist for alleged communist ties, the great director Jules Dassin filmed ‘Thieves’ Highway‘ (1949), a masterful story set inside the fruit-trucking industry. Though most of the film takes place in and around the Ferry Building in San Francisco, key early scenes at an apple orchard were filmed at George F. Ramondo’s orchard at 595 Gold Ridge Road in Sebastopol. Ramondo’s daughter Cheri Marcucci was only five years old when movie crews visited her home, but she still lives in the area and says that Dassin even borrowed some of Ramondo’s trucks for the filming. The property was sold long ago, but go there today and there’s still an old apple orchard off the side of the road; it’s between Roberts Orchard and Devoto Gardens, both with gated driveways.

In the opening exposition scene of a small town where Richard Conte’s character visits his family, locals will notice a familiar structure in the distance—it’s the Petaluma Grain Mill on Copeland Street. In the foreground is the old Petaluma Junior High School.

The long trucking episodes in Thieves’ Highway feature not only the most incredible tire-changing scene in the history of cinema, but also an epic crash that kills Millard Mitchell and sends apples flying across a field. Long thought to have been filmed on Highway 1 along the Sonoma Coast, the scene was actually shot at a hairpin turn on Highway 29, a mile from Old Faithful Geyser, just north of Calistoga. Take Highway 29 out of town, and right when it crosses Tubbs Lane and hits a tight, 180-degree turn, that’s the spot. If you don’t want to end up like Mitchell does in the movie, drive slowly.—Gabe Meline

[page]

‘The Birds’

Here’s a fun game for Santa Rosa residents: rent Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘The Birds’ and each time they mention Santa Rosa, scream loud and wave your hands over your head like you’re fighting off devil birds. It never fails to entertain. In 2012, it’s difficult to retrace the exact traces of the film’s shooting locations, since the town in the movie is actually a composite of Bodega, Bodega Bay and studio sets—but it’s not impossible. One thing: don’t go searching for the Tides Restaurant, featured so prominently throughout the film, since the original location of the restaurant burned down, just as it did in that great dramatic scene where the gas station blows up.

After The Birds was released in 1963, the Tides has been rebuilt twice; the original location was actually on the driveway leading up to the current restaurant, gift store and fish market. Fortunately, according to the book Footsteps in the Fog: Alfred Hitchcock’s San Francisco, the wharf where Tippi Hedren first sets sail to deliver the lovebirds to Kathy Brenner still exists. Other landmarks to look for: the Casino restaurant on Bodega Highway, where cast and crew ate meals during filming, and where chef Mark Malicki cooks his gourmet, locally sourced meals today; and the Potter Schoolhouse, up near the St. Teresa de Avila church in the actual town of Bodega (though don’t look for Annie Hayworth’s cottage next to the schoolhouse, as that was a false front made for the film).

The schoolhouse is a private residence, but don’t let that stop you from taking photos of yourself screaming in front of the grand, old white building on Bodega Lane. You also might want to recreate the scene where the schoolchildren run away from the schoolhouse as birds peck away at them, so head for Taylor Street Hill in Bodega Bay, and run and scream loud on your way down.

The Brenner Farm across the bay, where the final standoff with the birds occurs, was the home of Rose Gaffney, the woman behind the successful campaign to prevent PG&E from building a nuclear power plant on Bodega Head in the 1960s. Hitchcock transformed her broken-down ranch into the little farmhouse where Mitch Brenner lived with his mother and sister. To find it, drive down Westshore Road toward Bodega Head and look for a sign that says “Restricted Access-Bodega Marin Laboratory Housing” and a grove of cypress trees. Make sure to scream in terror when you get there.—Leilani Clark

‘Cheaper by the Dozen’

The opening credits for ‘Cheaper By the Dozen’ (2003), a schmaltzy family flick that Steve Martin fans should stay as far away from as possible, features a montage that could only be true in Hollywood. The film begins with shots of Martin jogging through the green hills of Petaluma—it’s supposed to be the middle west town of “Midland”—past sleepy cows and countryside, when suddenly he’s running down a small-town block and waving to neighbors, then just as quickly he’s back to the countryside, running up the porch of a farmhouse in the middle of nowhere.

Well, that small-town block is none other than Santa Rosa’s Railroad Square. In the clip, you can see Chevy’s in the background, and the buildings that currently house Furniture Depot, Old Town Furniture and Sacks Thrift Store. In a shot filmed through the window of Omelette Express, you can see the storefront across the street that’s now home to Jack and Tony’s Whiskey Bar and Cast Away Knit Shop.

Of course the farmhouse where Martin lives with his wife and 12 children isn’t in the Midwest either. The big, white Victorian is actually located on Two Rock Ranch at 1051 Walker Road in Petaluma. It’s a private home, owned by the Tresch family, and home to an organic dairy and an apple orchard.

Santa Rosa makes a reappearance at the end of the film when Martin and his son return to “Midland” by Amtrak. The station that they come home to is none other than the Railroad Square Train Depot—soon to be home to the SMART train. As the family hugs and makes nice, you can see the building where Flying Goat Coffee now resides, in the background, and a little bit of A’ Roma Roasters when the camera angle changes. One word of recommendation: there’s nothing wrong with watching the beginning and the end of this film and fast-forwarding straight through the middle. Your precious life span will thank you later.—Leilani Clark

‘Bandits’

Starring Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton and Cate Blanchett, ‘Bandits’ is both the true story of a bank-robber love triangle gone wrong and a tour of the North Bay’s funkiest hotels. First, there’s Mill Valley’s Fireside Inn, the white, freeway-side icon that’s been converted into apartments since the film’s 2001 release. After yet another successful heist, bandits Joe (Willis) and Terry (Thornton) and their all-too willing hostage (Blanchett) crash at the inn and gaze out over the marsh and freeway from its Colonial-style porch.

Then there’s Santa Rosa’s classic dive-mansion, the Flamingo Hotel. After an unlucky encounter with a Clover dairy truck (sporting the motto “Here’s lickin’ at you, kid”), Terry and Blanchett hide out at the hotel (2777 Fourth St., Santa Rosa) during a cosmetic convention. Forced to bunk together in a pink-and-white wallpapered room, the pair become intimate, sharing their secret fears (black-and-white movies, antique furniture), eating takeout and giving each other facials.

Finally, there’s Nick’s Cove (23240 Hwy. 1, Marshall). In Bandits, it looks like little more than a roadside biker bar, with a neon blue sign advertising “music and mollusks.” The trio finally falls apart at this West Marin destination (which has undergone significant remodels since 2001). They order whiskey and warm milk, Terry hyperventilates and collapses on the dance floor and the men brawl, crash through a coastal window and fall to the ground outside. Heartbroken and declaring that the male duo together make up “the perfect man,” Blanchett leaves her bank robbers, forcing them to head down the coast to the film’s final setting in Southern California.—Rachel Dovey

‘Peggy Sue Got Married’

‘Peggy Sue Got Married,’ Francis Ford Coppola’s 1986 film about a woman who travels back in time only to realize that she doesn’t want to change a thing, is chock-full of Santa Rosa and Petaluma sightings. When Peggy Sue travels back to 1960, she wakes in the Santa Rosa High School gym. In the next scene, the front of the school on Mendocino Avenue is featured in all its retro-glory. Later, Peggy and her friends drive through the streets of downtown Petaluma. They cruise past the classic iron-front buildings on Western Avenue, between Petaluma Boulevard and Kentucky Street, and the historic Lan-Mart building at 10 Kentucky St., now home to restaurants, a hair salon and a spa.

A grand building adorned with a stylized Carithers sign is at 101 Kentucky—it’s now a furniture store. Peggy’s family lives in a lovely white Victorian on the edge of Petaluma, located at 226 Liberty St., used for both interior and exterior scenes. It’s across the street from a house that was used in the filming of Mumford, and it recently was available for rent on Craigslist. Peggy visits her future husband Charlie (Nicolas Cage, weird as ever) at his home, located at 1006 D St., but don’t look for it; it was torn down over 10 years ago.

One of the coolest buildings in the movie is “the Donut Hole Cafe,” which was actually Millie’s Chili Bar at 600 Petaluma Blvd. S. A brownie-gift shop for a bit, it currently sits empty. Later in the film, Peggy Sue and her beatnik boyfriend head to Lena’s Restaurant in Santa Rosa. Lena’s, once the oldest restaurant in Santa Rosa, was razed in the ’90s; Chop’s Teen Club was built in its place at 509 Adams St. in Railroad Square. If you look carefully, down the street you can see the neon sign for Michele’s restaurant, now Stark’s Steakhouse. Unlike Kathleen Turner and Nick Cage, that building has aged relatively well.—Leilani Clark

‘Howard the Duck’

Is it legal to hunt ducks on the Petaluma River? If the duck in question is named Howard, it should be. Nine times out of 10, I have no idea what is going on in George Lucas’ 1987 disasterpiece ‘Howard the Duck.‘ But I do know the brown, lazy Petaluma River when I see it, and that police car taking a dive might have been the most sanitary thing to fall into it.

Should it prove too tempting to skip the foul-mouthed, raunchy, duck-from-another-world blockbuster, know that there are a few scenes shot in Petaluma. Western Avenue is featured, the aforementioned river and a glimpse of the Petaluma Bridge during Howard’s scamper away from law enforcement (they should have just let him go) in a small-engine glider. That’s it.

Maybe the short screen-time is why Petaluma officials and residents don’t exactly boast about being in the movie. Or maybe it’s Lea Thompson’s line, “I just can’t resist your intense animal magnetism,” while she and Howard are snuggling up to watch late-night television.—Nicolas Grizzle

[page]

‘The Village of the Damned’ and ‘The Fog’

In 1980, horror flick maestro John Carpenter filmed the fishing-town-leper-zombie massacre flick ‘The Fog’ around Inverness and the Point Reyes Lighthouse. It’s at the creepy, wind-swept lighthouse that ’80s film star Adrienne Barbeau, as small-town radio DJ Stevie Wayne, first has to defend herself from the dooms-bearing killer fog. Carpenter liked West Marin so much that he ended up buying a house in Inverness, and 15 years later again chose the area as a film location for the 1995 remake of ‘Village of the Damned.‘ (Later, a Point Reyes local told the San Francisco Chronicle that the filmmakers treatment of locals was “really, really rude and harsh.”)

The film, like it’s predecessor, features long, dramatic shots of waves crashing against the Point Reyes Seashore. Christopher Reeve, in his last role before being paralyzed in a horse-riding accident, tutors the evil, white-haired children in the red schoolhouse that’s still home to Nicasio Elementary School located at 5555 Nicasio Valley Road. The white-and-green-shingled house where Reeve lives with his doomed-to-suicide wife is in Chimney Rock, just above Drake’s Estuary. To get there, head west on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, through Inverness, until you get to the Chimney Rock turn off; walk about a mile down the trail to see the house, now used as a residence for the park staff.

Other locations in Nicasio are prominently featured, including the town’s main square, baseball field, and reservoir. The red barn where the children start their malevolent commune is actually owned by the federal park district and was used for storage at the time of filming. With all this in mind, West Marin might just be the perfect spot for a John Carpenter film tour, eh? —Leilani Clark

‘American Graffiti’

Filmed in the summer of 1972, George Lucas’ coming-of-age classic ‘American Graffiti’ pays tribute to the groovin’ tunes and stylin’ rides that defined his adolescence while cruising the strip—then Highway 99—in Modesto, Calif., during 1962. To capture the true experience of “the strip” in its heyday, Lucas selected San Rafael as the film’s central location for its then-authentic sixties-era look and feel. But after neighborhood residents barraged the set with noise complaints, the cast and crew hurriedly relocated to downtown Petaluma, known by the movie’s fans today as “Graffiti Town.”

Once every year in May, American Graffiti enthusiasts prowl the streets in their candy-colored classic cars, groove to live rock ‘n’ roll and revisit some of the film’s moviemaking history. Among the neighborhood blocks and streets captured in the movie—Petaluma Boulevard, D Street and Washington Street (the main drag for cruisers)—film watchers can also catch some of Petaluma’s architectural history.

In front of the old opera house (149 Kentucky St.) Curt Henderson, played by Richard Dreyfuss, is connived into joining the Pharaohs gang; today the opera house is occupied by law offices and an Irish pub, but on the outside, the building remains unchanged. Fans will also recognize the used car lot right next to the McNear Building (15–23 Petaluma Blvd. N.) where Henderson manacles the axle of a police car to a metal pole. Today, the lot remains as a small enclave for parking cars, but next door, then the State Movie Theater, is the Mystic Theatre.—Michael Shufro

‘Gattaca’

On watching ‘Gattaca’ again for the first time since 1997, I am reminded of two things: first, how bad of an actor Ethan Hawke really is, and second, how cute Jude Law was when he still had all of his hair. For those who haven’t seen it, the film tells the story of Vincent, who is born naturally to love-struck parents sometime in the “not too distant future,” at a time when most babies are formulated for genetic perfection at birth. Naturally, Vincent is born with a heart condition, one that banishes him to a life of low-wage, manual labor, when all he wants to do is fly to the stars. He comes up with a plot that allows him access to the elite Gattaca Space Center, working his way up to a space trip as a “borrowed ladder.”

The scenes at the neo-futuristic headquarters were actually filmed at the Marin Civic Center; it was used for both exterior and interior shots, including some really gorgeous images of the building from a distance at night. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1957, the large, sand-colored architectural wonder can’t be missed from its perch above Highway 101. It can’t be missed in the movie either, appearing so much that it’s practically another character. At one point, Vincent cleans the 80-foot central dome, which is home to the central branch of the Marin County Library. In another scene, rocket ships fly in the sky beyond the massive skylights that line the ceiling of the upper floor.

For those who want to recreate their favorite Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke scenes from the film, the Marin Civic Center is free to enter on most weekdays. One-hour long docent tours are offered on Wednesdays at 10:30am for $5, no reservations required. And since NASA recently declared Gattaca to be the most plausible science-fiction movie ever made, maybe someday soon genetically modified humans will be running the Marin Civic Center instead of regular, gene-flawed politicians.—Leilani Clark

‘Pollyanna’

Set in turn-of-the-century Smalltown, U.S.A., Disney’s ‘Pollyanna’ prominently features Santa Rosa’s famed McDonald Mansion at 1015 McDonald Ave. as the home of the main characters. There are plenty of great shots of the three-story home, but when you see it today—it’s in the final stages of a complete restoration—keep in mind that a false facade was added by Disney to make it look more like New England.

The gated driveways on the gem of McDonald Avenue give view to a stellar garden and the half-faux Victorian architecture. And if you’re looking for the tree that Pollyanna uses trying to sneak back inside after a late night out, you won’t find it—that was a set, too. The film features scenery from other areas of Sonoma and Napa counties, and reportedly cast members stayed at the Flamingo Hotel during shooting in 1959. The movie didn’t live up to box-office expectations, at the time earning only half of the projected $6 million.—Nicolas Grizzle

‘This Earth Is Mine’

‘This Earth Is Mine’ opens with a close-up of grapes, a shot of Rock Hudson in a cowboy hat and a gorgeous, sweeping view of Inglenook Winery. And the film, dear reader, goes downhill from there. Shot on location in the Napa Valley, the film offers fine vineyard scenery and the inclusion of Claude Rains and Jean Simmons. But the movie drags, despite the best intentions of the screenwriters. The plot centers around two winemaking families struggling to get by during Prohibition. Bootleggers want to buy their wares, but only one, Hudson, is willing to sell. He also knocks up a vineyard worker—a “common, scheming trollop”—and courts Simmons, who is unimpressed with winery life. “Do you like our valley?” she’s asked upon arrival. “It’s very large,” she sighs.

Shots of barrels containing 1927 Cabernet aren’t the only fun props here. Period-era cars and dialogue featuring the real-life Stag’s Leap pepper the film, and an old depot—Yountville? Rutherford?—figures into several scenes.

Fun trivia: In one scene, Rock Hudson needs to perform a chip bud graft, and local resident Jim Pavon not only taught Rock how to bud, but loaned his budding box and knife for shooting.—Gabe Meline

[page]

‘The Lady from Shanghai’

Quintessentially, ‘The Lady from Shanghai’ (1947) is a San Francisco film, but there’s a wonderful scene in Sausalito where Rita Hayworth arrives in town on a boat and is met by Orson Welles on the pier. The cove is Whaler’s Cove, right in front of the old Valhalla bar and restaurant, owned by the infamous madam Sally Stanford (in the film, the building says “Walhalla”). The building is still there, at 201 Bridgeway on the end of Main Street, though it’s been built out to extend into the bay a bit. The long wooden boardwalk where Welles and Hayworth meet is still there, as is a noticeably towering house with a corner turret in the background; Jack London is rumored to have written Sea Wolf while staying there. A bus drives along a road in the background—that’s Bridgeway—and views of the Sausalito hillside evince a small town over 60 years ago.—Gabe Meline

‘Indiana Jones and Temple of Doom’

One of the many trademark George Lucas Films, ‘Indiana Jones & the Temple of Doom’ (1984) is one of those Harrison Ford classics that will not be forgotten. What many aren’t aware of is how close some of the filming locations actually were in comparison to how far around the globe Indy traveled in his adventures. For example, the beginning scene of the film takes place in China, where a simple exchange between Indy and some Chinese gangsters turns into gunplay and a chase scene. When they end up at the Shanghai Airport, however, it’s actually the old Hamilton Air Force Base in Novato.

The base is long gone now, replaced by new development. If you’re feeling up for the quest to see if there is any resemblance left there, feel free to take a look. After that, head north on 101 and take the Lucas Valley Road exit. Go east to 5858 Lucas Valley Road, and there you will see parts of the Nicasio location of Skywalker ranch. Around here is also where things start to look familiar from the end of Indiana Jones, when Indy comes back to the Mayapor Village. The exact location isn’t known, and since Skywalker Ranch is private enough itself, you probably don’t want to sit around outside long enough to be asked by authorities to beat it. However, we do know that this particular ending scene was shot on a hill above the ranch, while the upper half was a matte painting.—Jennifer Cuddy

‘I Know What You Did Last Summer’

Originally set to be completely filmed in North Carolina, ‘I Know What You Did Last Summer’ (1997) opens with shots from Sonoma coastlines. Back in the ’90s prime “horror-thriller” films, this movie showed that you just don’t hit someone with your car and dump them into the ocean, because they probably will come back to stalk and kill you.

In the beginning of the movie we see a beautiful ocean scene with four naive college-bound students driving along the coast. This is Highway 1, the Pacific Coast Highway north of Fort Ross. The teens are also shown having a typical bonfire on the beach at Schoolhouse Beach, south of Jenner. As they continue their careless joyride along the coast, we also see shots of Campbell Cove in Bodega Bay and Fort Ross. Rumor has it that the filmmakers wanted to build a bridge at Fort Ross, but the waves were too choppy so they had to move to Kolmer Cove instead. Either way, the drive from Bodega up to Fort Ross should look familiar in an eerie way. Watch out for limping fishermen on the road at night, and try not to hang out of the moon roof of your car—that’s just not smart to do.—Jennifer Cuddy

‘Dirty Harry’

Filmed mostly in San Francisco, 1971’s ‘Dirty Harry’ tells the story of one notorious cop that doesn’t take crap from anyone, even his superiors at the SFPD.

The infamous ending scene takes place in Larkspur, near the Sir Francis Drake Boulevard exit. These days, when heading out in this direction there’s a shopping mall, parking lots and a Marriott hotel in place of the quarry where it used to be a less developed area. The Corte Madera Creek railway bridge that Harry jumps off of and onto the school bus has now been mostly demolished in order to widen the roads. Fortunately, there is still a part of the bridge left located at 12 East Sir Francis Drake Boulevard.

When following down the road, the scenery of Mount Tam in the background still stands boldly just like in 1971. The location of the final showdown between Harry, Scorpio and the .44 Magnum doesn’t exist anymore, but there’s a convenient ferry station to take you back to the city to explore more Dirty Harry locations downtown.—Jennifer Cuddy