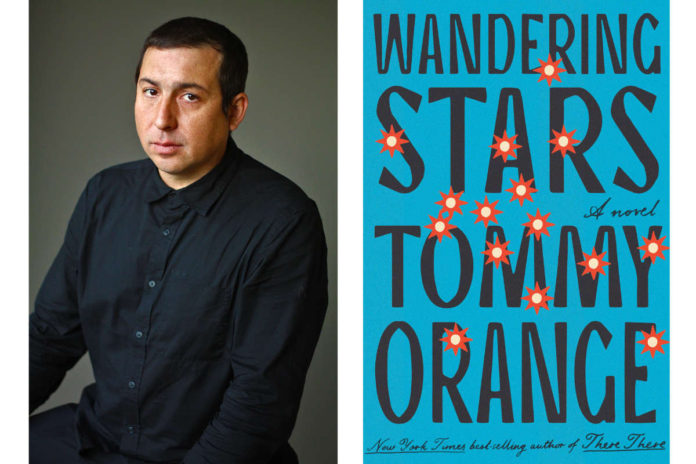

The difficulty in beginning a conversation with Oakland-based, New York Times best-selling novelist and writer Tommy Orange is deciding which direction to go.

We could shift into reverse and march through his earliest years, being born and raised in the Dimond District by his parents, his father Cheyenne, his mother white and a Christian; playing roller hockey and noodling on his guitar during adolescence; graduating from college with a degree in sound engineering before working at San Leandro’s Gray Wolf Books and wondering what to do with his life. Beginning to write and investigate his Cheyenne and Arapaho of Oklahoma tribal identity and citizenship, he pursued and earned a master’s in fine arts from the Institute of American Indian Arts.

Or, is it best to plunge into the more recent here-and-now? After all, there’s the irresistible magnetism of Orange’s fascinating short stories. Published in literary magazines such as McSweeney’s and Zyzzyva, he nudged and eventually pushed hard against Native American tropes and misrepresentations—such as the iconic, mythical, stoic images of Indians as somehow immune from the brutal violence practiced against them throughout American history.

Ultimately, Orange’s literary energy culminated and was mirrored in the momentous reception to his debut novel, There There (2018). Awards stacked themselves into towers surrounding his first work of fiction, which places as its centerpiece a powwow that attracts—for different reasons—members of a multigenerational, urban Native American family. There There was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize and received in 2019 the American Book Award and the PEN/Hemingway Award.

Orange was suddenly and overwhelmingly heralded as a new voice in Indian literature and the visibility was widespread, resulting in demand for public appearances as a Native American thought leader. More honors, including nominations for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, the Audie Award for Multi-voiced Performance, and two Goodreads Choice Awards: Best Fiction and Best Debut Goodreads Author, also came his way.

All of this is ripe material for discussion, but instead there is the immediate moment and future—which is where the focus should begin.

Orange’s sophomore book, Wandering Stars (Alfred A. Knopf, March 2024), is already attracting starred reviews and notable buzz in the industry and with the general public. His second novel is in some ways a sequel to his first book and follows three generations of the Red Feather family with a story that begins by leaping back to the family’s pre-Oakland history in Colorado, where the Sand Creek Massacre destroys an Indian community and sends a young survivor, Jude Star, to the Fort Marion Prison Castle in Florida.

For three years Star, along with other young Indian children, is essentially imprisoned and must learn English and practice Christianity—all actions meant to erase her Native history and culture, and any traces of Indian identity. The narrative follows Star’s descendants, who end up in Oakland struggling with mixed success through the legacy of annihilation and trauma by white America: bias, prejudice, PTSD, opiate addiction, school shootings and more.

“With There There I could point at any character and give you the difficulty number,” says Orange. “With writing Wandering Stars, the whole thing was just hard. They talk about sophomore albums being difficult, and especially when you’re having success, you’re having to prove that you can still do it, or top it, or people just wanna see you fall from a height, because that’s a spectacle. There was weird pressure.”

Orange found writing during Covid severely challenging. He’s never aspired to write historical fiction because he feels it’s been overdone in Native American literature, but the story about the boarding school had reached a deep place in his soul that compelled him to persist. In part, his Southern Cheyenne tribe is at the story’s heart, and he recognized that the real-life facts and events represented a wrenching origin story that held within it the assimilation, relocation and dislocation that urban Natives experience.

While writing early scenes featuring Star, he researched intensely, changed tense back and forth, rewrote sections and cut out entire episodes as if, having stared into history’s bright lights, he was determined to chase and capture the afterimages. A sense of place had formed the foundation of There There, and the Red Feather family was firmly established, providing structure for Wandering Stars and allowing him to delve deep into character.

“It’s a more interior book, and that’s something I like to do in writing in general,” he says. “It’s where I started and where my characters begin. Fiction can do it in a way that other forms cannot. There’s an over-emphasized voice that says writing is about scene. But we have TV and movies; they’ll always be better than description of scene.”

Orange tried to bring back all of the characters from There There. “When I first started, I picked up right after the powwow,” he says. “In collaboration with my editor, we wanted it to be a standalone and not redundant. I fought to the end to keep the filmmaker character from There There and recently cannibalized some of that writing for my next book. I’ll get his stuff in somehow.”

Although Orange doesn’t keep lists, several of his characters do. The character Lony composes lists that he considers puzzles. “He wasn’t going to be a writer, but it was a way for him to collect information because he’s so curious,” Orange says. “It was a way for him to express that without him having a narrative voice.”

Another list serves a profound purpose and appears from a meditation by Orvil, Lony’s older brother. “He lists the names of tribes, reads them aloud and speaks them into existence,” Orange says. “He felt shame—and this is also my shame in not having the Ohlone people mentioned the way I should have in There There—about not knowing the names of the [nearly 200] tribes in California. I was happy because these are unknown, hard-to-say names that have been reduced to Indian or Native American. With the names of each tribe comes a ton of language, worldview and creation stories.”

Wandering Stars is written with Orange’s natural musicality and instinctive humor. Before becoming a writer, he says he was “a fully failed musician,” and music was his first art form. As a writer, he reads his words aloud; even recording other people reading his words to better hear the cadences, rhythms and sentence structures. He’s considering releasing compositions he’s written that might have been what Orvil, also a songwriter, would have written.

Orange is pleased to be asked about the humor in his work. “It’s rarely mentioned, even in my inner circles, but it was [John Kennedy Toole’s] Confederacy of Dunces that first made me want to write a novel,” he says. “I didn’t know books could make you laugh but also be sad and dark. I don’t try to be funny, but it’s important to render life and lively dialogue, to balance heavy matter, release tension, and provide payoff and lift for the reader having to sit with heaviness. In my family, I was the one cracking a joke during something super intense.”

Inevitably, the conversation wraps up with future thoughts, plans and dreams. Orange is astonished that half the country thinks Donald Trump is a hero instead of a person he says is “brazenly stupid and lacking in humanity, humor, taste—and a despicable human,” whose re-election as president would leave us doomed. On a more upbeat note, he’s thrilled Lily Gladstone won Golden Globe’s Best Female Actor and that Native American television shows, books and across-the-spectrum output from Native artists is thriving. “I just hope it’s a sustaining energy for our representation,” he says. “I believe art can change lives.”

He’s sold his third novel, which leaves behind the characters in his first two novels with a book full of dark humor, the world of Pretendians—ethnic fraud—run rampant and contemporary voices. Meanwhile, There There is being adapted for television, and he says the all-Native American cast it will showcase will raise the visibility of Indigenous people. He’s also writing and hoping to have produced a screenplay, and he laughs—but only lightly—at a suggestion he might compose the film score.

Limitless possibility is the perfect note upon which the conversation reaches its end.