Josh Churchman is a West Marin resident who runs his small commercial fishing boats out of the Bolinas Lagoon and Bodega Bay in Sonoma County. He’s 67 and has been fishing his whole life. ‘The Whale That Lit the World’ (Hidden City Press; $12) is his first book. Here are some excerpts.

The Fishing Disease

. . . To this day, whenever I see a new body of water, I wonder what kind of fish might be living in it. I wonder what I could use to catch some of them. My mom taught me not to keep fish I wasn’t planning to eat, but she didn’t kill my love of fish or fishing.

Fishermen are a strange breed of people. It is almost like we have some kind of ancient disease. The disease is strikingly different for each individual it infects. For some it is a freshwater disease that takes a fisherman to rivers and lakes. For others, it involves an ocean.

The disease may come on suddenly, later in life, or it may be present at birth and follow the fisherman to his grave. Some people have it strong in their life, and then it just vanishes. Some people can be cured, but not very many.

Of all the diseases mankind faces in this world, it is far from the worst affliction someone could encounter. Water is most of what we are, and what is a fish if it is not all about the water? Wondering what lives in that water, and how to catch it, defines a fisherman. Turning it all into a profession is just one of the more advanced symptoms of a deeply infected individual.

People who love to fish dream of finding a really good spot and having it to themselves. Secrecy is just one of the many idiosyncrasies that go along with living with the disease. A close friend will ask you where you caught those fish, and your gut instinct will be to evade without really lying, to minimize and deflect an open, honest answer.

It has been said that ninety percent of the fish are caught by ten percent of the fishermen. I do believe that this is true. However, the ten percent is never the same ten percent year after year. Some guys get hot, and then they are not. Some people improve with age, and some do not.

People will say fishing is all about luck, but luck is such an elusive creature. Bad luck is just as common as good luck.

If you are lucky enough to find an exceptional spot, you would be a fool to show it to very many people. An older frustrated fisherman once told me, “What takes years to learn takes minutes to copy.” He was surrounded by other boats.

For the past thirty years, I have been a very lucky fisherman. I didn’t feel particularly lucky at the time, but in hindsight, I was living the “good old days” and did not recognize it for what it truly was. I had a lot of fun making money catching fish. Having fun and making money do not combine very often.

Fishing is a hard way to make a living, or it can be a way to not make a living. Fishing can put you in some of the most beautiful surroundings this world has to offer, or it can put you in places that are so dangerous that you have to be lucky to survive. . . .

The Cordell Bank

Cordell Bank, located fifty miles west of San Francisco, is part of an underwater mountain range that sits perched on the edge of the continental shelf. The top of the bank lies 120 feet from the surface. A mile west of that high spot, it drops off the continental shelf to six thousand feet deep.

Eleven thousand years ago, the Cordell Bank was oceanfront property. Sea levels have risen 340 feet since then. The Golden Gate Bridge would have been built over an immense river rather than ocean. This ancient river system mave have helped carve the deep Bodega Canyon that bends around the western edge of the Cordell Bank.

Mysterious things live around the Cordell. It is not only fish and birds and whales and dolphins that like this spot. Drifting in a boat, with the engines off, there are shadows under the surface that can’t be clearly seen. More creatures live here than any other place I have ever been. You can’t see what the shadows are, but they are certainly felt in your sensory soul.

I often feel I am being watched when I fish the bank, watched by intelligent life forms that are curious about me and why I am there. I sense their demand for a certain amount of respect. I am a visitor, not a local boy.

It would be ridiculous to try to pretend that these feelings do not exist. It is as though the spot is sacred and protected by the guardians of the deep. I have seen white sharks here that rival, in size, the model they used in the movie Jaws. I have seen several blue whales that might have set world records for size. Eighty or one hundred feet long and weighing two hundred tons each. I saw a white sperm whale at the bank that could have been related to Moby Dick. It is the creatures I haven’t seen that scare me the most.

[page]

Part of me knows that there are not “mysterious creatures” that lurk in the deep waters, eluding human contact. Part of me hopes there are unseen and intelligent creatures that have avoided human contact. This is another example of a dialectic born at sea: It is a big ocean, and we haven’t seen all there is to see.

One thing is for sure, there are creatures out there that can and will eat you. There are whales so big that a flick of their tail would sink my little boat. . . .

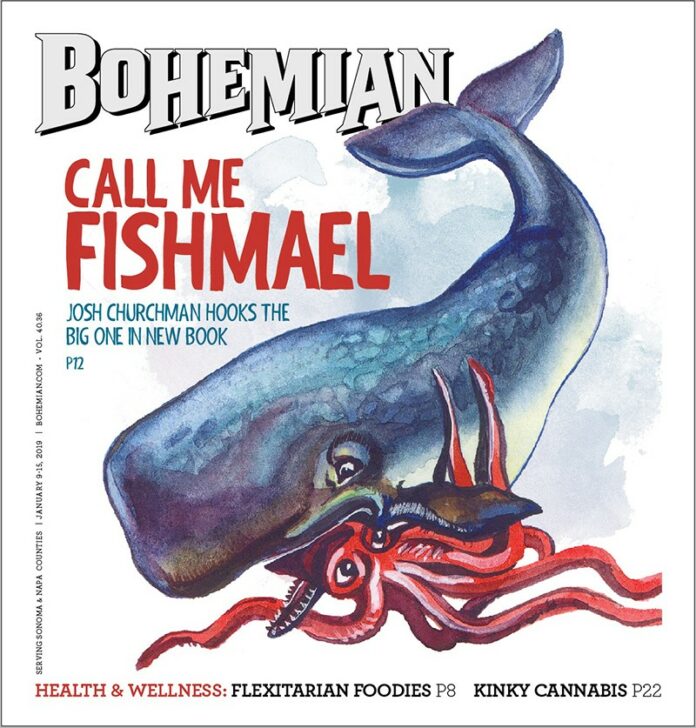

Call Me Fishmael

The first sperm whale I ever saw was also my first white whale spotting. It was one of those “unforgettable” moments. Somehow or somewhere I had placed the existence of a white whale in the “mythical” category. Not true or impossible, just unlikely.

It was in the late 1970s, when my boat was still fairly new. I had been venturing farther and farther out looking for new spots to fish. . . .

It was one of those clear calm days that do not happen many times during a year of fishing. We had traveled far from shore, and we kept on going further out because the fish would not bite our hooks in all the usual spots.

By early afternoon, we were so far out that the curve of the Earth masked the land thirty miles away. We had finally reached a place we call the Buffalo Grounds. It was one of my secret spots located twelve miles west of the Farallon Islands and twenty miles short of the Cordell Bank, along the edge of the continental shelf, due west from San Francisco.

This particular spot was once a well-kept secret and an oasis of life on most days. This was not one of those oasis days. The fish were not in the mood to bite our hooks, no matter where we went.

There are very few places left in any of the great oceans that man has not plundered. The Buffalo Grounds are not “virgin” by any stretch of the imagination, but by virtue of its remote location and unique topography it remains one of the “secret spots” to this day. It does not appear on any chart.

If you are going to bump into something unusual in the ocean, it will probably be at a spot like the Buffalo Grounds. It may be a secret spot to mankind, but the creatures who live in the area know all about it.

On this day, and on most of the days I spend at sea, I was with my friend Kenny. We have fished together for many years, and we have seen a wide variety of marine life in our travels together. Whales and dolphins had always been a highlight for us on any trip offshore.

The whale first surfaced a mile or so to the west of us, took a few breaths of air or “blows,” then disappeared. It was a white whale, and I remember feeling excited that there actually were white whales after all. We had no idea what kind of whale it was, but we agree it had been large and it was white.

This was a lonely day for our little boat. We had not seen another vessel all day long. No other boats, no dolphins, not many fish, and no other whales; we were thirty miles from the nearest land in a homemade boat. Naturally we were elated to see the first whale, and it was a white one. Things were looking up.

The most famous whale of all time was a white sperm whale like this one. The whale haunted the very soul of another fisherman named Captain Ahab. In the story of Moby Dick, Herman Melville had the whale eventually sinking Ahab’s ship, killing all but one, Ishmael, who lived to tell the tale. But that was just a story, and this was real. . . .

We were drifting with the motors off, quiet and peaceful. The view from the deck of a boat that is out past the sight of land is a bit unnerving. All directions are as one, the rolling swells being the only constant reference. The swells passing under the boat are like waves of thought drifting through your mind. At first you see a pattern to both the thoughts and the swell, but patterns shift and uncertainty replaces certainty. Without a compass to guide us home, we would surely circle back upon ourselves, hopelessly lost.

Watching for whales is a game of patience. Looking out, you see nothing but sky and water when the whale is down. When they do come up for a breath, it is not for long. They blow out, then take air in, and they are gone again. You can usually tell which direction they are traveling, but that is about all you get.

A few minutes later, it resurfaced a half mile away. It was actually more tan than pure white upon closer inspection. When we first saw it, the whale was heading west-south-west on its way to sunny Hawaii. Now it had changed course. Apparently, this whale had echo-located our little boat. We were the only boat in this vast expanse of the sea and somehow this whale figured out we were there. Instead of heading in the direction of Hawaii, it was now heading right for us. We were going to be checked out. . . .

[page]

At a quarter mile, Kenny and I could both agree that this was our first sperm whale. The narrow head, the wrinkled skin, the forward slant to its blow, it had all the defining characteristics that distinguish this whale from the rest. It was quite a sight to see it glowing, tannish-white under the surface of the clear blue green of the Pacific.

Kenny is a very patient man. He is tall, has dark hair and eyes, and he can fix anything anywhere at any time. We have fished together for over twenty years and in all that time I have only seen him truly alarmed once. This was not that one time, but it was close.

At three hundred yards, it was clear that we were in this whale’s way. It became vividly clear that the size of the whale had increased as the distance between us decreased. We saw that our boat was less than half the size of the whale. Interest had turned to amazement, amazement had turned to alarm. Obviously one of us had to move out of the other’s way.

Banging on the side of the boat with our wooden gaffs and yelling at the whale seem like dumb things in retrospect, but so many things we do in life seem dumb when we have had time to think them over. All of this is happening faster than I can tell the story, so there was little time for reflective thinking. Both of us stood there banging on the boat and yelling at that big old white sperm whale as he advanced upon us. The whale was not impressed.

At fifty yards, I had a wave of inspiration. Start my motors and prepare for evasive action. My homemade boat is equipped with two powerful outboard motors, and it can literally jump to twenty miles an hour when we are not loaded down with fish. The problem was the fact that our fishing lines were still down and they both had fish on them, and the water was six hundred feet deep. There was no time to reel in the lines.

The thought of cutting off my rigs never even entered my mind. I don’t think either of us was concerned for our safety; we were just stunned and amazed. Of all the whales over all the years, not one had ever tried to ram the boat.

At twenty yards, the size and majesty of our white whale was very impressive, and the memory has remained clear over the years. The glow of its huge near-white body a few feet under the surface of the sea, no more than twenty yards away, was beauty with a twist.

This was a real sea monster. Everything about this whale exuded power. Fearless is an understatement. This whale had no rivals, and it knew it. One slap from this whale’s tail would crush my boat and kill us both.

I put the boat in gear and moved out of its way. The whale never turned. It passed the spot where we had been just moments before and began a slow descent into the depths. The glow of its powerful body gradually diminished, and finally faded away. We never saw it again.

Squid Vicious

I think I do need sea monsters to believe in. Somewhere in our psyche, there may be the hope, and the fear, that there is life on this planet that is smart and dangerous and elusive, and we haven’t seen it yet.

The giant squid is the ultimate lurker. It will see you long before you will see it. I am so glad there is a creature like this, and at the same time, I hope I never see one from the deck of my little boat.

It is a sign of intelligence for the squid to have avoided contact with humans? Or is it simply the fact that the squid live in an area that is difficult for humans to visit? Is it a conscious choice or pure luck that they have eluded mankind for hundreds of years?

Does the whale eat the giant squid, or does the squid eat the whale? Most squid swim in packs. Do giant squid swim in packs, too? Could a whale defend itself against a group of thirty giant squid?

One solitary giant squid is one thing; a school of them is an entirely different scenario. Would the mighty sperm whale stand a chance against [a] pack of two hundred hungry squid? The whale is on a time schedule, and the squid is not. At the end of a dive, the whale needs air, and this is when I would attack a whale if I were a squid. If we can just keep him from reaching the surface, he will weaken quickly.

If squid only live four or five years, how do they get enough food to grow to be fifty feet long? Eating a whale would help. Squid have a system that literally grinds up the food they eat before it reaches their stomach. This makes it very hard to analyze the stomach contents. Nobody really knows what the squid are eating. No scientists have ever seen a squid capture a whale, and they probably never will. Does this mean it never happens?