Not long ago, a Colorado-born farm boy named Verlyn Klinkenborg wrote a book titled Making Hay, which made him famous in certain literary circles. Klinkenborg went on to write and publish several other books that made him even more famous, including More Scenes from the Rural Life. He also became a columnist for the New York Times.

Not surprisingly, Making Hay didn’t make hay itself famous. (For those who don’t know, hay is a cured grass not a grain, and it’s not straw either; it’s a many splendored thing unto itself.) Thirty-one years after Klinkenborg’s first book was published, the complex art of making hay is still largely a secret known only to those who actually practice it.

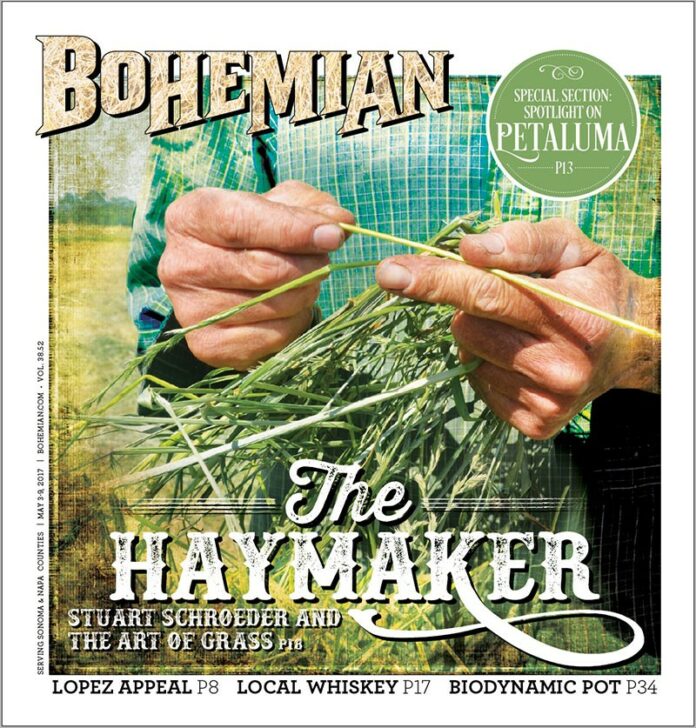

Doug Mosel knows almost all of the secrets. Born in Nebraska in 1943, he came to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1994 and settled in Ukiah in 1999, where he founded the Mendocino Grain Project in 2009. More about Mosel at a later date. Here the focus is on his friend and partner Stuart Schroeder, who lives in Sonoma County, and who has never written a book about hay or about the rural life, though he could write volumes about both topics.

Schroeder grew up on a farm in the Midwest, where he was born in 1960 and where his family raised cattle, chickens and pigs. They also grew soybeans, corn, oats, sunflowers, alfalfa and tons of hay. All across Iowa and Nebraska, diversified farming of that sort is now mostly a thing of the past. These days, corn and soybeans are the big commercial crops.

Schroeder left home many years ago to seek his fortune and explore the world beyond the Midwest, taking a few farming skills with him. Now, with his wife, Denise Cadman, he grows all kinds of heirloom beans and grains, along with organic melons, potatoes, tomatoes and broccoli at Stone Horse, a beautiful farm on the outskirts of Sebastopol and on the edge of the Laguna de Santa Rosa.

Schroeder grows hay by the ton. Indeed, one might describe him as a hay maven and a kind of hay apostle. “Making hay was a giant step forward in human history,” he says on an overcast spring morning. “It made the domestication of animals possible and provided a way to feed cows, sheep and goats during winter months when plants are dormant and grazing in fields isn’t possible.”

Not surprisingly, Schroeder encourages young farmers to grow hay and learn to love it as he does. Perhaps more to the point, he feeds his hay to his three workhorses—Ben, Bonnie and Baron—that he uses to plow and cultivate his fields. The hay that he grows also helps with soil conservation, no small matter on a parcel of land that slopes and where erosion can be a problem when there’s heavy rain and run-off, as was the case this winter.

All across northern California hay crops tend to be grown in winter when they don’t need irrigation. If a farmer wants a second or, rarely, a third cutting, then irrigation is usually necessary.

Schroeder keeps a close eye on changing weather patterns and on the ever-shifting shape of the land. “If I see even a little soil moving, it freaks me out,” he says. “Not on my soil! That’s my goal.”

Schroeder sells his melons and his vegetables at the Sebastopol Farmers Market, and he shows up at social functions in the county and drinks wine, mixes with the crowds and makes polite conversation. But he’d rather be on the farm making hay or tinkering with his tedder, a kind of mechanized pitchfork that allows cut hay to cure effectively and to look and smell much better than hay that develops mold. His goal is to make a palatable and nutritious product and to enjoy the whole haymaking process.

“The fact is, I don’t like to leave the farm,” Schroeder says. “If I have my druthers, I’d rather not be out and about.”

One of the unsung heroes of Sonoma County agriculture, Schroeder doesn’t advertise his farm and doesn’t want it to be a destination for tourists from the city. He’s also a Jack of nearly all trades who has dozens of tools used to repair much of the farm machinery that he always keeps in good running condition. Schroeder buys old, discarded equipment, fixes it and puts it to work. Yes, he uses a tractor—an old International—as well as his three horses, whom he treats like members of the family. The tractor saves time, but it’s noisy. With the horses, he can hear the birds sing.

[page]

“I’m the welfare agent for my horses,” Schroeder says. “They get dental and medical attention and pedicures, too.” He added, “Horses like to eat and go, and eat and go day and night. I supply that psychological need.”

Primitive agriculture of the sort that the pioneers practiced isn’t for Schroeder, though he likes to keep farming simple, to stay close to the earth and maintain what he calls a “quiet profile.” But every now and then he enjoys going public and talking about hay, which rarely if ever receives as much attention as those two high-profile crops, grapes and marijuana.

Hay plays a big part in Sonoma County agriculture. Indeed, it’s a major crop all the way from Sears Point to Petaluma and Healdsburg, and from Valley Ford to the outskirts of Santa Rosa. Haymakers like Schroeder labor long hours in the hot sun and on windy, chilly days, too, especially when the skies threaten rain. They’re a kind of tribe known mostly to one another.

At 57, Schroeder still works like a man of 27. He and his fellow haymakers plant, cultivate, harvest, bale and then stack 50-pound bales in barns that provide habitat for owls. On big farms, stacking machinery does the work quickly and efficiently. Schroeder, Doug Mosel and their friends don’t ask for applause, though the work they do ought to be applauded.

“Oh, goodness—any place you see livestock, you know that hay will be grown,” Mosel says. “It’s almost everywhere.”

Schroeder sells a good part of the hay he grows. It’s a good source of income. “People with horses always want good, clean, weed-free hay,” he says, adding, “I like to think I grow good hay.” Indeed, Mosel gives Schroeder’s hay the highest marks.

Standing in a field that he’s recently seeded, Schroeder gazes at the red-winged black birds that dart overhead. He wears a red cap, a red jacket, jeans and high boots, and he looks as though he could be cast as the iconic farmer in a Hollywood movie about a heroic haymaker who battles the elements, survives floods and droughts, and comes out ahead of the game.

“Not everyone makes good hay,” Schroeder says without sounding competitive or boastful. “You need to have the right balance of air and moisture. You need to know when to plant and when to harvest. You don’t want the hay to become brittle and dry out. When you open a bale, you want to see green inside.”

In Ukiah, 70 or so miles north of Schroeder’s Stone Horse Farm, Mosel adds his own observations. “To grow good hay, you have to be a keen observer and read the fields,” he says. “You have to know grasses and harvest them when they’re young and tender and not tall and stemmy.” Mosel harvests most of the hay in Anderson Valley. “I also put almost all of it up,” he says. “I cut it, rake it and bail it. Then the ranchers pick it up and store it.”

Not all of the hay that’s sold in Sonoma County is grown here, though it’s often advertised as Sonoma hay. There’s just not enough land here to grow the quantities of hay needed to support the livestock population, so much of the horse hay sold in Sonoma County comes from the Central Valley and Scott Valley in Siskiyou County.

In fall when he’s harvesting, and in spring when he’s planting, Schroeder’s life gets hectic and even a bit crazy both outdoors and indoors. He and his wife do a huge amount of canning, bottling, preserving and pickling.

“A farmer eats what he can’t sell and a gardener sells what he can’t eat,” Schroeder says. He and Denise do a bit of both.

There’s almost nothing that feels better to him than a barn full of hay.

“It’s my larder,” Schroeder says. ‘It gives me a tremendous sense of security to see all those bales under my roof.”

The bales might also make Schroeder’s workhorses feel secure knowing they won’t go hungry in winter.

Jonah Raskin is the author of ‘Field Days: A Year of Farming, Eating and Drinking Wine in California.’