Jeremy Nichols is a board member of the nonprofit Bird Rescue Center that serves Sonoma County, and he is troubled. The county is kicking the bird hospital out of its Quonset hut in the middle of 82 acres of public property known as Chanate.

Forested hills straddle Chanate Road as it winds through eastern Santa Rosa toward the ashes of Fountaingrove. The county has promised the land to William Gallaher, a local banker who develops senior living communities and single-family homes.

Gallaher’s partner in the deal, Komron Shahhosseini, is a planning commissioner for Sonoma County—a relationship which may pose a conflict of interest, according to a Haas School of Business ethics expert who reviewed details of the deal.

Hundreds of Santa Rosans, including Nichols, have mobilized to stop the sale, objecting to its terms at public meetings, in letters to the editor and in a lawsuit that went to trial in Superior Court last Friday in front of Judge René Auguste Chouteau. The trial took three hours, and the judge is expected to rule within 30 days on whether the development deal can go forward.

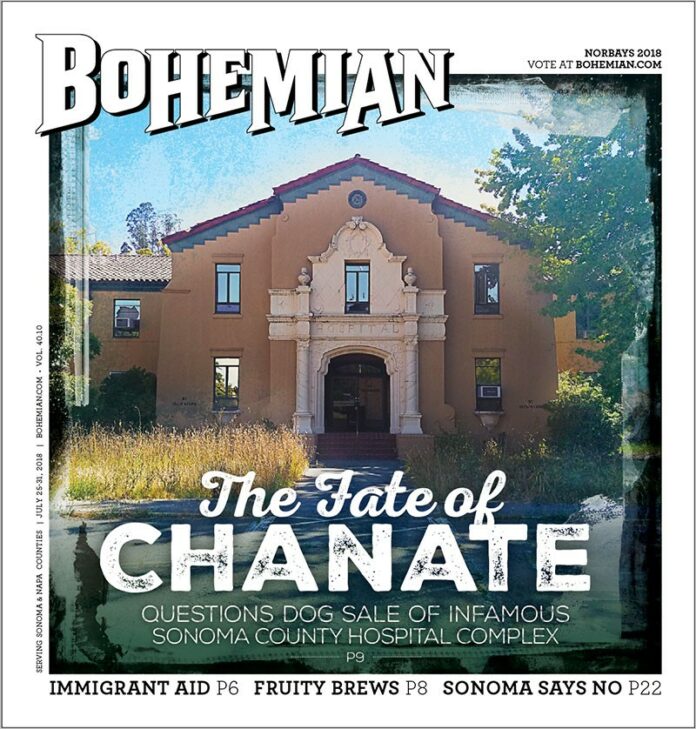

In early July, Nichols and two members of the activist group Friends of Chanate took me on a walking tour. Since the 1870s, the Chanate property has been the dumping ground for the county’s social and medical ills. It was originally the site of a work farm for low-income residents, then a public hospital complex. Now it’s ragged and falling down.

In the cemetery where the county used to bury indigents rests Walter F. McCoy. His suicide in 1934 was headlined by the

Press Democrat, “Dying Man Slashes Throat to Avoid Entering Hospital Here,” notes Nichols, who restored the graveyard.

We stroll past abandoned, rotting medical buildings that served the leprous, the insane and the penniless. As we skirt a plywood-sealed juvenile jail, a line from Bob Dylan floats by: “And the only sound that’s left after the ambulances go / Cinderella sweeping up on Desolation Row.”

There are some signs of human activity. There’s a public health laboratory, a psychiatric clinic that processes the involuntarily committed. The unexpectedly dead of Santa Rosa await their autopsies, shelved in cardboard boxes inside an old boiler and laundry building repurposed as the city morgue.

We circumvent bottle-strewn homeless encampments. A pond stagnates, its outflow blocked by graffiti-swirled concrete. There is the tangy smell of nearby cannabis gardens.

For the Friends, Chanate is a historical treasure, a wildlife preserve, a public resource awaiting reassignment for social good. And for them that future is threatened by Gallaher, who they believe is being allowed to develop Chanate in violation of environmental regulations, open-meeting laws and on the cheap.

Last August, the Friends hired former State Sen. Noreen Evans of O’Brien Watters & Davis LLP to sue Sonoma County and Gallaher’s Chanate Community Development Partners LLC. The arc of the case highlights the county’s dire need for affordable housing, community-based healthcare services and, it must be said, smarter governance.

Gallaher proposes to construct up to 860 homes and apartment units with recreational facilities and a shopping center. The Friends of Chanate favor building fewer than 400 units and want to scale back any commercial development. They fear more activity will overwhelm traffic, water and educational infrastructures. And they are particularly concerned about traffic gridlock if future wildfires compel area residents to evacuate, as happened last fall.

Safety concerns aside, the Friends want Gallaher to pay market value for Chanate. They fear he will flip it to another developer for a quick profit. And they do not trust local officials to look after the public’s interest. Our tour guide, Carol Vellutini, is not joking when she says she will lay down in front of the bulldozers should the lawsuit fail.

THE BACKSTORY

In 2014, Sonoma County supervisors closed down the heart of Chanate, its public hospital, which had last been upgraded in the 1970s. They said it cost too much to seismically retrofit. Despite pleas from scores of medical professionals to keep the facilities operational, the supervisors put Chanate up for sale as a housing development at a minimum price of $15 million.

A nationwide request for proposals required that 20 percent of the homes be affordable to families with very low incomes. It required the developer to demolish buildings. Because the land is inside city limits, its building permits and zoning and environmental authorizations, called entitlements, must be approved by Santa Rosa’s council and planners.

Entitling a big development project is not a slam dunk, especially when there is substantial public resistance. Non-local developers were wary of becoming embroiled in a community slugfest. Two local builders found the moxie to push ahead.

Petaluma-based Curt Johansen spent $100,000 researching how to build 400 homes with sustainable bells and energy-saving whistles. He offered to pay whatever the fair market value of the land turned out to be after the entitlement process solidified development costs.

Sonoma County records show that only two supervisors perused Johansen’s proposal before the board rejected it, mostly sight unseen. Johansen blames the slight on his lack of participation in local politics, noting that he has never made a campaign donation to a Sonoma County politician.

In February 2017, the county’s real estate planners and lawyers began negotiating behind closed doors with the Gallaher-Shahhosseini partnership. The board of supervisors discussed the value of the project in closed sessions, the content of which remains secret.

Gallaher’s proposal was championed by supervisor Shirlee Zane, who had appointed Shahhosseini to the planning commission in 2009. It is worth noting that Zane has received $63,000 in campaign contributions from Gallaher, who is a prolific funder of local politicians. Zane declined to comment for this story.

[page]

In June 2017, the supervisors approved a Disposition and Development Agreement (DDA) with Gallaher and Shahhosseini. The property is priced substantially less than the market value of Chanate as appraised by the county. The supervisors accepted Gallaher’s offer of between $6 million and $12.5 million. The final amount is contingent upon the number of homes eventually permitted by Santa Rosa as the project drills through a mountain of red tape.

The supervisors also appropriated $300,000 to subsidize Gallaher and Shahhosseini’s quest to get the project entitled by Santa Rosa.

The Friends then filed a lawsuit to terminate the agreement, contending that the market

value of Chanate is more than

$30 million and that the county is not allowed to sell it for less.

How much is Chanate worth?

The value of Chanate partly depends on whether the land is sliced by earthquake faults. At present, there are two expert opinions: one says there might be fractures; the other, there might not be fractures. Nobody knows. The supervisors decided to value the land as if there are active earthquake faults, which made it cheaper, since fault-zones are harder to develop.

The value of the land also depends upon the value of the proposed improvements. And that value is contingent upon the development being green-lighted by county, city and state planning, permitting and environmental agencies. The county hired an appraiser. In July 2016, the Ward Levy Appraisal Group of Santa Rosa valued a “hypothetically” developed Chanate at

$30.64 million, assuming the existence of earthquake faults.

The appraisal assumed that permission would be granted to construct 600 units of housing and 33,000 square feet of commercial space. It calculated the value of a finished project similar to that later proposed by Gallaher and Shahhosseini at $275 million.

Appraisals are based on formulas that consider shifting market conditions and construction costs. Residential land is typically valued at

10 percent of the cost of building, so $30 million is a reasonable projection for 600 homes worth more than a quarter billion dollars. Increasing the number of the homes increases the fair market value of the land, of course.

The Ward Levy appraisal assumes that the hospital buildings would be demolished by the developer at a cost of $6 million. With a credit for demolition costs, the market value of the land for 600 units pencils to roughly $24 million. Adding 260 more units for a total of 860, as Gallaher has proposed, brings the bottom line land value to $34 million.

That amount is nearly three times Gallaher’s offer.

To recap: In 2015, the Sonoma County stated it would not accept less than $15 million for the property. During a series of

closed meetings, the price fell to $12.5 million for 860 homes. If Gallaher builds 400 residences, the agreed price falls to $6 million, which is also below market value projections for the land, which Ward Levy valued at $40,000 per residential unit.

A DAY IN COURT

The Friend’s lawsuit asks the court to stop the development agreement because the below market price is an unallowable “gift of public funds” to the developer. It asks for the deal to be set aside because the supervisors allegedly violated the Brown Act, which requires timely disclosure of what is discussed in closed sessions and with whom. It argues that the agreement should be terminated because the supervisors failed to conduct an environmental review of the proposed project before approving the sale to the Gallaher-Shahhosseini partnership.

According to the lawsuit, the agreement does not prohibit Gallaher and Shahhosseini from flipping the land to another developer for a “windfall” profit, without building anything.

Attorneys for the county and the developer have filed arguments disputing the core of the Friend’s claims largely by framing the Development and Disposition Agreement as a market value sales transaction and not as a development project with environmental impacts. Gallaher’s Santa Rosa–based attorney, Tina Wallis, told me that the $6–$12.5 million price is not a gift of public funds because those amounts are the market value for an unpermitted property.

Attorney Noreen Evans argues that the property is only worth money to a developer if it is fully permitted. Why buy it otherwise?

The county’s director of general services, Caroline Judy, told the supervisors in a hearing on June 20, 2017, “The sale price is below the appraised value.” The county has projected property tax revenue from the development based on a market value of

$275 million.

Justifying the below market value offer, county officials told the supervisors that the low price is offset by social benefits to the county, including 160 units of affordable housing, which they value at $71 million.

That’s an absurd calculation, say the Friends. The developer and its nonprofit partners will make money on the affordable housing element through sales, rents and state and federal subsidies and grants. The real question is how much money can Gallaher and his partners make if they pay fair market values for fully entitled land? What is his projected profit rate?

Gallaher did not respond to repeated email and telephone requests for comment.

[page]

CONFLICTED INTEREST?

Shahhosseini referred the Bohemian to the Chanate partnership’s attorney, Wallis, who declined to reveal the names of the LLC’s investors, if there are any, or the projected rate of profit for the venture. Wallis also pushed back against any suggestion that Shahhosseini’s county position created a conflict of interest. “Mr. Shahhosseini acted as private citizen, and this matter was not before the Planning Commission,” Wallis said.

Nobody disputes that, as a developer, Shahhosseini had a leading role in negotiations with Sonoma County for the sale of Chanate. According to Gallaher’s development proposal, Shahhosseini is a “partner and co-founder” and “principal” alongside Gallaher in Chanate Community Development Partners LLC. The Disposition and Development Agreement that governs the deal names Shahhosseini as project manager; he represents the partnership in community meetings.

“Mr. Gallaher is the sole and managing member of the LLC,” Wallis said. But in an October 2016 email to the city obtained by Evans, Shahhosseini clarified, “Bill is the managing partner; I am a partner and project manager.”

As a member of the Sonoma County Planning Commission, Shahhosseini regulates planning and zoning matters in the unincorporated areas of the county that surround Santa Rosa. Briana Khan of the county administrator’s office told the Bohemian that the planning commission has not been directly involved in negotiating the Chanate deal.

The Disposition and Development Agreement prohibits county employees and officials from having a financial interest in the Chanate agreement:

6.17 CONFLICT OF INTEREST. No County Party [defined as county employees and officials] shall have any personal interest, direct or indirect, in this Agreement, nor shall any such County Party participate in any decision relating to the Agreement which affects his or her personal interests or the interests of any corporation, partnership or association in which he or she is directly or indirectly involved.

The clause is a double whammy: it forbids any county employee or official from having any personal interest in the Chanate agreement. It then states that just in case a county official has such an interest, that person is not allowed to make decisions relating to the agreement.

Shahhosseini is a county official with a personal interest in the Chanate agreement who makes decisions regarding the Chanate agreement as its project manager and a declared partner in the development company.

After reviewing the agreement and Gallaher’s proposal,

Christine M. Rosen, a professor in corporate ethics at the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, opined, “It sounds like a conflict of interest to me, and a violation of the agreement this developer and Sonoma County have signed.”

In a series of exchanges with the Bohemian, Wallis said that since Shahhosseini wielded no direct authority over the Chanate agreement as a planning commissioner, there is no conflict of interest. But the issue is not whether he acted on the agreement in his capacity as a planning commissioner, which he did not, apparently; the issue is that Shahhosseini is a county officer who has an interest in the agreement, and who makes decisions regarding it in his capacity as a developer.

Khan told the Bohemian that Shahhosseini could not have a conflict of interest because, quoting the development agreement, “as an [appointed] member of the planning commission, [Shahhosseini] is not an elected official, officer, agent, employee or representative of the County in any way.”

True, he was not elected; he was appointed. However, the planning commission’s bylaws clearly define its members as county officers and agents and representatives with official, quasi-judicial duties and as “part of the Sonoma County Planning Agency,” a government body.

Khan said that the county deliberately did not add appointed officials to the list of those who are not allowed to have an interest in the contract because no appointed official played a role in the negotiation of the development agreement. She did not respond to a query noting that the agreement was made with an appointed official in his private capacity.

Whether a conflict of interest exists is an issue that’s normally settled administratively or judicially. But is it OK for a county official, appointed, elected, or otherwise, to be awarded a county contract worth tens of millions of dollars?