Making a Connection

Janet Orsi

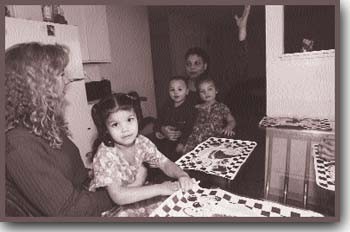

Home Team: Deanna Avery, right, and her three children are among the local homeless families being helped through an innovative case-management program.

Agency pairs homeless families, volunteers to deal with national problem

By Zack Stentz

THE CHANGE is dramatic. Tess–the thoughtful, soft-spoken college student and retail employee who sits in the Family Connection offices explaining the circumstances of her life–is a far cry from the homeless, formerly drug-addicted mother who emerged from treatment nearly two years ago in an unfamiliar county with no job, no housing, two suitcases of belongings, and three children to care for. “It was a very hard time for me,” says Tess, with a certain amount of understatement.

“I was just coming out of the Women’s Recovery Center for drugs and alcohol abuse. I had spent eight and a half months there, so we were in a tough spot, and all my family was in the East Bay. But I knew where I wanted to go with my life. I knew I wanted to stay off drugs and go in the right direction.

“In the lifestyle I had lived for six years,” she continues, “with the drugs, and the alcohol, there was no honesty, no trust–you were just out there on your own, and it’s a rough life out there.”

Headquartered in a modest building amid the cluster of homeless support organizations on Morgan Street in Santa Rosa just east of Highway 101, the Family Connection serves between 20 and 30 families at a time. And on a modest scale at least, the program seems to be successfully moving beyond short-term assistance to tackle some of the root causes behind Sonoma County’s intractable homeless problem. “Well, our better than 90 percent success ratio speaks for itself,” says Pam Fisher, Family Connection’s energetic, blunt-spoken director.

The concept behind the program sounds so simple as to seem blindingly obvious: Match homeless families with community volunteers who can then help them line up housing, child care, and employment and otherwise reintegrate into society’s mainstream.

And while the Family Connection isn’t a silver-bullet solution to all Sonoma County’s problems of poverty and homelessness, the effects of the program on individuals have been dramatic.

One of its co-founders is Michael De Vore, a local minister and advocate for the homeless who developed the program in 1988 in conjunction with Susan Marshall and several other community activists after hearing about a similar program operating in Sacramento. “The program in Sacramento was church-based, sort of a church-to-family operation,” recalls Marshall, who still works at Family Connection and pops in from an adjoining office to share her thoughts. “People here were interested in the idea, but modified it to become a team-to-family [operation], so the connections between people could be more personal.”

“This is a very unusual model,” Fisher acknowledges. “I mean, we still need the emergency shelters and standard ‘roof over head’ services, but studies have shown that the highly successful anti-poverty programs all involve the formation of real relationships over time.”

So just how real are the relationships developed and nurtured by the Family Connection? As real as any human connection one could hope for, to judge by the warm embraces exchanged by team members John and Polly Post and Leigh Ross and their assigned family of a mother, Tess, and her children Melissa, Christina, and Winslow. The adults all wax eloquently on the positive, healing nature of the program.

While some in the program opt to terminate the relationship gracefully at the end of the year, Tess and her team actually found themselves extending their commitment to each other beyond the standard duration. “They’ve been together a year and seven months,” says Linda Shoreman, the Family Connection caseworker for this particular team. And according to Fisher, the bond the volunteers feel with Tess and her children isn’t unusual among Family Connection teams and families. “Many families and at least some team members stay together indefinitely,” says Fisher.

The reason for the enduring strength of their bond goes straight to the heart of the Family Connection’s philosophy, which views the breakdown of traditional neighborhood and community-based support networks as a key cause of homelessness and vulnerability. Hillary Rodham Clinton’s famous slogan “It takes a village to raise a child” may have become a chestnut through overuse, but Fisher believes in the truth behind the cliché.

“We’re artificially creating small-scale communities and support networks for people who don’t have them,” she explains. “And there are a lot of us who don’t, these days.”

Sonoma County certainly has no shortage of families in dire need of assistance from which to choose. “Five hundred and fifty families go through the shelter system each year,” says Marshall, “but there are many more than that who are car camping, living with relatives, or otherwise aren’t eligible for the shelters.”

Once referred through the county’s shelters, the selected families are matched with the teams of volunteers. As to how families and teams are matched with one another, Fisher explains: “We look for people whose skills complement each other. Maybe one team member’s a good listener and very empathetic, while another one is a type A person, a doer.”

The volunteers are then put through a training session to make sure they are ready for the rigors of staying involved in the life of a family of strangers for a year. To facilitate an immediate bonding between the family and team members, the caseworker typically sets them to work meeting the family’s most immediate need. “That’s typically housing,” says Fisher. “So we get them started helping the family find a place. Sometimes they give them rides to look for housing, or take care of their kids, or help them deal with landlords. And then there’s the matter of finding furnishings you need to outfit an entire household.”

No small task, to judge from Tess’ case.

“When I first got out of the Women’s Recovery Center, I had two suitcases and three backpacks,” recalls Tess, who, instead of returning to the East Bay, opted to stay in Sonoma County after her treatment. “That’s all.”

“And that’s with three kids, in a place she’s never lived before,” adds Polly Post.

“No silverware, no blankets, no sheets,” the intense, 30-ish Ross enumerates. “But we all got together, and asked people we knew, and even put up flyers, and ended up getting everything we needed.”

After the initial move-in hurdles like the ones described by Ross get cleared, the support given to the family in question usually ends up being determined by what the particular team can bring to bear. “Just as every family has unique needs, each team has unique skills and talents and connections, just like any real family or circle of friends in a community does,” Fisher explains.

In some cases, the help might involve lining up child care or helping a family member brush up on job interview skills. In the case of Tess and her family, much of the help centered around Tess’ desire to continue her education. “I really wanted to go back to school,” Tess says. “And Polly, especially, really encouraged me, and John [Post] was there too.”

“And Leigh [Ross] helped her a lot with the applications and paperwork and financial aid forms,” the ever self-effacing Polly adds.

Currently holding down a job while studying toward her MFCC (“I’d really like to counsel others with substance problems,” Tess says), and with three cheerful, intelligent children and a roof over her head, Tess would seem to be a veritable Family Connection poster girl. But Fisher and the other staffers and participants admit that the road to a success like Tess’ isn’t always a smooth one.

For instance, the program’s training often doesn’t entirely prepare volunteers for the realities of working with families from radically different backgrounds. “There are chances for people to back out along the way,” Fisher says. “Team members who don’t get along with each other can be matched with other people; and families and teams who aren’t meshing can also be reassigned, though that rarely happens.”

“That 12 hours of training don’t begin to tell you what you’re getting into,” agrees Polly Post, definitely speaking with the voice of experience. “There was a lot we had to learn along the way, like the difference between caretaking and caregiving.”

That is one of Family Connection’s most vexing difficulties: how to help the group’s mostly middle-class volunteers offer practical help and support to poor families without coming across as condescending liberal do-gooders.

“It’s a major issue that we’re very aware of,” says Fisher, sharing a knowing look with fellow staffer Nancy Frank that indicates the matter has been the subject of much discussion. “Nancy and I come from backgrounds of poverty ourselves, so we’re both really aware of those issues, and can sometimes catch them. We do have working-class and poor volunteers, and we added a section into our training that deals with class-based cultural differences, which is something you very rarely see addressed in so-called diversity workshops. But despite all the training, it happens anyway.”

“The problem isn’t so much condescension as judging,” adds Frank. “You need to acknowledge the judgment and move beyond it, such as in a case when a team member doesn’t agree with a family’s decision.”

“It’s hard not to be judgmental sometimes, like with the family who called the Psychic Friends hotline for career advice,” agrees Ross, rolling her eyes in recollection of the incident.

Yet the team members, too, say they had many of their perceptions and beliefs altered by their interactions with Tess. “I’ve learned a great deal about the welfare system, and how hard the lack of affordable housing and transportation makes life for people like Tess,” says John Post. “And I’ve been so inspired by Tess’ wonderful spirit and by her family’s desire to turn their lives around.

“I’m not sure I could have done it in their shoes.”

Tess breaks eye contact and looks down at the floor, a little embarrassed but obviously moved by the compliment.

Indeed, despite their markedly different economic and racial backgrounds, as they sit around the table joking and sharing stories, the relationship between Tess, her kids, and the members of her team seems more like the bond of a close-knit extended family than the bond between a social worker and client. The casual touching on the arm, the finishing of each others’ sentences, the trotting out of oft-told stories and anecdotes–all attest to a depth and genuineness of feeling among the people in the room.

“We’re both single women in the community, so we have a lot of those issues in common,” says Ross of her kinship with Tess. “And when something terrible’s going on my life, I can call her at 11:30 at night to cry, and she can do the same with me.”

For more information on the Family Connection or to volunteer as a team member, call 579-3630.

From the December 19-25, 1996 issue of the Sonoma Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1996 Metrosa, Inc.