The Fed-Ex package delivered to Ben Kinmont’s eponymously named bookshop doesn’t look like much. It’s about the size of large sandwich. Kinmont removes the white plastic sleeve to reveal a manila envelope. Like a Russian doll, underneath that layer is another. Once he takes that off—a colorful wrapping of striped paper—a thin layer of tissue is all that remains. Obviously, someone took pains to bundle up this package.

Finally the object was revealed: a stout book with a leathery, almost waxy cover made from stiff vellum.

Vellum is made from sheepskin, and is an ancient book-cover material. The book came from a bookseller and friend of Kinmont’s in Madrid. It’s a first edition of Arte de Cozina written by Francisco Martínez Montiño, head chef for King Philip III of Spain. It was published in 1611. That’s right. It’s a 404-year-old cookbook, a piece of art and history you can make dinner from tonight.

There are only three other copies known to exist, two of which are in national libraries in Spain. The price? Twenty-five thousand dollars.

“What’s extremely sexy about this book for me is it’s the first edition of a book that went into certainly more than 50 different editions,” says Kinmont. “So to find the first edition of one these few titles is really rare and unusual.”

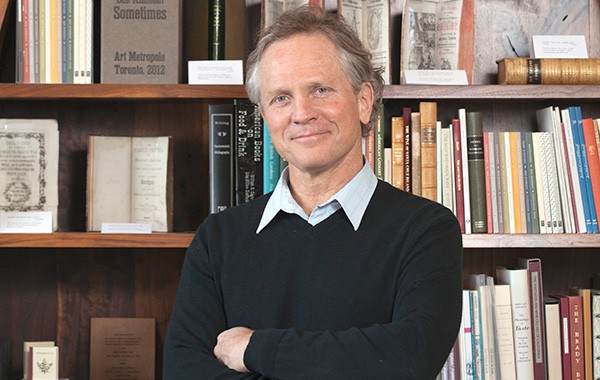

Kinmont, 51, a thin, soft-spoken man with graying hair that he tucks behind his ears, is an antiquarian bookseller who specializes in food and wine books from the 15th to the early 19th centuries. Quite the niche.

“I think the early books have a more interesting story to tell. Books prior to 1840 were better made.”

His knowledge of rare books and gastronomy make him one of the top antiquarian booksellers anywhere.

“He’s certainly the best in the world in my opinion,” says Jonathan Hill, a New York–based bookseller who specializes in antiquarian science books. First edition works from Aristotle, Copernicus, Galileo and Newton have passed through his hands. Serious books.

Hill was Kinmont’s mentor for 12 years and encouraged Kinmont to open his own bookshop. “I said, ‘You really have a gift to be a first-class bookseller on your own,'” Hill says. “And he is.”

“As a food and wine lover myself, I’ve always been drawn to Kinmont’s eye,” says Susan Benne, executive director of New York’s Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America. “He has an excellent eye.”

Kinmont acknowledges the education he got from Hill. He began by “koshering” books, checking to see if the books were complete and intact. Sometimes, facsimiles of damaged pages are sewn into the binding, dramatically diminishing their value. Kinmont also researched books to confirm what edition they were. Koshering is the heart of dealing in rare books.

“That’s how you judge one bookseller next to another, their ability to do that,” he says.

When it came time to strike out on his own, Kinmont had to choose a specialty.

“In the rare-book world, you must decide, when you leave your mentor, do you burn your bridges or continue to stay close to your mentor.”

Rather than sell rare science books and compete with Hill, Kinmont decided to focus on food and wine.

“I chose to continue to be close my mentor,” he says.

They’re still good friends today.

Kinmont notes that it was also important to choose a subject he was excited about, and clearly gastronomy is something that excites him.

“Unlike most fields in the rare-book world, when you look at a cookbook, you can actually cook from it,” he says. “There’s something wonderfully accessible about gastronomy and cookery that doesn’t exist in most subjects.” One of Kinmont’s favorite dishes is for a sweet omelet, which he cooks for his children, that he found in a 19th-century English manuscript.

As the rare-book world has become more globalized and specialized over the past 30 years, many bookshops have closed, and it’s now hard for the public to see antiquarian books. Even though few people walk in off the street to buy a $10,000 book on potato cookery, Kinmont says it’s important to have a public face. His shop (“Open by chance and appointment” reads the lettering on the glass front door) is at the Barlow in Sebastopol. However, he’s planning to leave the Barlow in the next six to 12 months because of what he says are continually escalating common area fees at the retail complex. He’ll relocate to a new shop he’s building behind his home on North Main Street.

[page]

Kinmont was interested in books at an early age. He’s the child of what he calls “hippie parents.” He’s father is a conceptual artist and his mother is a Zen Buddhist and herbologist. He’s always loved rare books. “You either have a love of rare books or you don’t,” he says. “It’s called bibliophilia.”

He got the bug early. When he was a child growing up in Sonoma County, Kinmont was given an early but tattered copy of Robinson Crusoe by a relative. “I always treasured that book and had it around,” he says.

As a student in American studies at Pomona College, Kinmont visited Oxford University on an exchange program and discovered the wide world of rare books at the Bodleian Library. He could handle any book he wanted.

“It just blew my mind,” he says. “I’d never had that experience before. It was there that I got to develop a sense of what period books I enjoyed, and what it was like to use them.”

Like his father, Kinmont is also a conceptual artist whose work has been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the SFMOMA and many other galleries and museums. His career as a bookseller actually began as an art project. Kinmont is interested in how artists make a living in different economic systems. In a capitalist system, artists sell art in galleries. But, Kinmont says, there are also gift economies, collaborative economies, maintenance economies and others.

In 1988, Kinmont created a conceptual art piece called Sometimes a Nicer Sculpture Is to be Able to Provide a Living for Your Family. This “art as idea” was the act of selling books.

“The idea of supporting the family as a sculptural act was something that interested me,” Kinmont says.

That project continues on—in the form of his bookshop. Kinmont views not only the books, but the shop itself and even the invoices as objets d’art.

In addition to koshering books, the other key part of Kinmont’s work involves matching books with collectors and institutions. The relationships he builds with buyers are long-term, and are sometimes taken up by other family members when a collector passes away.

“When you’re a bookseller, your role is finding the right collector and putting that collector with the right book,” he says.

In an age of Kindles and digitized texts, a bookstore that sells 400-year-old books isn’t exactly cutting-edge. Kinmont had long complained about “disembodied” digital texts, and finally did something about it by opening his shop.

“I really wanted to create the opportunity for the public to come by and see what a 16th-century binding looks like,” he says, “or a 19th-century manuscript, to realize that’s there’s the text you are reading, but also a reading that occurs when you look at a book as an object.”

Indeed, there is a certain thrill that comes from holding a four-century-old book. It feels heavier than it actually is.

Interest in antique books on food and wine is surging, but Kinmont says the field is still in its infancy. It was only in the 1960s, when academics began to study gastronomy for its social and political meaning, that collectors began seeking out rare books on the subject. Before that, food production wasn’t seen as a subject of much intellectual value.

“That evolution in bookselling is, of course, parallel to the evolution of cultural production at a particular time,” says Kinmont.

Cookbooks and works on agriculture provide a window into social, political and economic worlds by documenting what people ate, where food came from and how it was produced. And sometimes, Kinmont notes, this is a tough point to sell to older librarians.

“They don’t take [gastronomy] seriously,” he says. “But if it’s a younger librarian, it’s more likely I don’t need to explain how one can unlock historical issues and ideas when reading a cookbook.”

Because he sells books to private collectors and institutions, Kinmont’s shop could be anywhere, but he clearly loves Sonoma County. When he’s not in his store, you might find him surfing at Dillon Beach or Doran Park. You’ll know Kinmont spent the morning in the water when you see his wetsuit hanging on the railing in front of his shop.

But given the reverence for good food, wine, beer and coffee in Sonoma County, the location suits his business and passions well.

“My subject matter is really about the activities that this area is known for,” Kinmont says. “It’s really a very good fit.”

Ben Kinmont Bookseller, 6780 Depot St., Sebastopol. 707.829.8715.