Wag the Mob

Phil Caruso

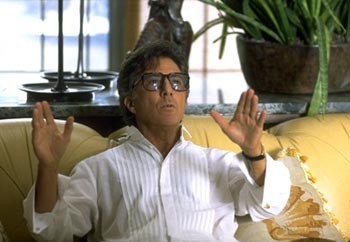

War Game: Dustin Hoffman plays a Hollywood producer who produces a war.

Activist David Harris wants you to be in the know

By David Templeton

In his ongoing quest for the ultimate post-film conversation, David Templeton met with controversial political author David Harris to see the dark-humored White House satire Wag the Dog.

FOR A MAN TOUTED AS both a larger-than-life superhero of the 1960s anti-war movement and as a brazenly demonic scourge against all that is red, white, and blue, David Harris comes off as a pretty normal guy. No horns or halo are readily apparent; he checks his watch a lot (so he won’t be late picking up his kids from school); he drinks decaf espresso. Yet few people have inspired as much saintly praise and hissing vilification as the man now sitting at a mall’s food-court table, having just seen Wag the Dog, Barry Levinson’s offbeat satire about savvy spin doctors (Robert De Niro and Dustin Hoffman) who fake a war in order to re-elect a sleazy president.

For his part, Harris has experienced enough spin for a lifetime. His book Dreams Die Hard (St. Martin’s Press, 1982) is considered a classic exploration of disillusioned idealism, and 1996’s double-whammy of Our War: What We Did in Vietnam and What It Did to Us (Timeless Books) and The Last Stand: The War Between Wall Street and Main Street over California’s Ancient Redwoods (Sierra Club Books) are still stirring up lively public discussions.

But despite a decades-long career as a journalist and author, Harris will probably always be best known as the draft-resister–once married to singer Joan Baez–whose much-televised refusal to go to Vietnam landed him in prison, galvanizing a nationwide movement against then-President Lyndon B. Johnson and the ever-escalating war. He is currently working on a book about another masterful government spin job, the audacious U.S. invasion of Panama.

“It’s a little like whistling on the deck of the Titanic, this movie,” Harris says of Wag the Dog, grinning amiably while leaning backward in his chair. “On one hand, it’s a shallow, slight little comedy, but it’s about precisely the thing that is killing us as a culture, the greatest threat to American democracy: our growing inability to claim and recognize reality, our inability to distinguish the truth from the spin.

“We’ve become a galvanic-response culture,” he continues. “If I can go on television and make your palms sweat within the first 15 seconds of my appearance, I can become the president of the United States. If I can’t, I can’t, and it doesn’t matter how smart or wise I am.

“The only weapons we have against that kind of stuff is our own capacity for perspective and self-examination, to take and examine our own response to it. And yet we are losing that ability more and more every day.”

Harris points out that the movie’s central idea–that a national emergency such as the film’s make-believe war against Albania can be whipped up and spoon-fed to a gullible populace–is nothing new.

“Go back to the Spanish-American War,” he says. “In those pre-electronic days, William Randolph Hearst started that war in order to sell papers. It’s only a half-step from there to what happened in this film.

“In fact,” he continues, “there was an incident at the beginning of the Vietnam War that was more or less manufactured. In late 1964, early 1965, after the Tonkin Gulf resolution, we made the decision to upgrade from an adviser’s war to a combat war. The Tonkin Gulf incident began it, but that incident–a supposed attack on American destroyers by North Vietnamese patrol boats–never happened. There was no attack. It was a mistake made by a confused radar operator that was capitalized on by Johnson, who was looking for a place to put his foot down. The missiles that the radar supposedly saw turned out to be the destroyer’s own wake–classic condition for radar confusion.”

Harris, leaning forward now, is warming up to the story.

“The military told Johnson to sit tight until they could find out if anything had really occurred or not,” he relates, “but Johnson said, ‘Fuck it.’ He commenced bombing raids on North Vietnam that night.

“They never bothered to figure out what really happened until after the whole goddamn war was over 10 years later,” he concludes.

“At that point, the government was just beginning to learn how to control the press,” Harris says. “By the time you get to the Gulf War, there is no independent press. The press are all waiting in some building for a guy from the government to tell them what’s going on and to distribute a video of a bomb going down a smokestack in Baghdad.”

Harris pauses. He sips his coffee, checks his watch, shrugs, and says, “The one optimistic thing about all these developments is that it still takes a lot of work and effort to make us want to go to war. It’s not natural for us to put ourselves through that, to go out and die in battle. In order to get us into that position, there has to be an extraordinary situation. You have to train people and manipulate images.

“Unfortunately, it is getting easier to do that. It’s the great irony of the information age that while huge amounts of information have now flooded into the culture through electronic media and the Internet, our grasp of the truth has gotten weaker and weaker and weaker.

“But you know what I think?”

He leans closer.

“Ultimately, it’s not the government’s job to tell the truth,” he states. “It’s not the media’s job. It’s our job.” He waves his arms to include himself and everyone else milling about the mall.

“It’s our job,” Harris repeats, “to be people who are sophisticated enough to sort out what the truth is instead of just lapping up whatever is the most comfortable story to believe.

“That’s the only antidote to what will otherwise destroy us.”

From the January 15-21, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.