Troubles Aplenty

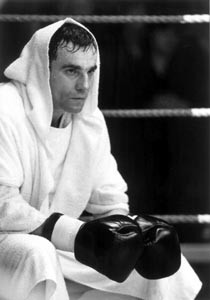

In this Corner: Daniel Day-Lewis plays a failing Irish pugilist in ‘The Boxer.’

Theologian Jim Conlon is knocked out by the ethical hits of ‘The Boxer’

By David Templeton

In his ongoing quest for the ultimate post-film conversation, David Templeton cold-calls Irish-born author/theologian Jim Conlon and winds up in a surprising discussion stemming from the troubling IRA drama The Boxer.

S URE, WE COULD DO THAT,” offers theologian Jim Conlon, somewhat tentatively, after listening to my phoned-in pitch to take him to the movies. I’ve explained that a whole spate of spiritually themed films are currently out in the theaters, including Kundun–about the early life of the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader–and Fallen, the tale of demented angels wreaking havoc on Earth.

“I should tell you, though,” Conlon says, “the movie I’ve been thinking about is The Boxer, with Daniel Day-Lewis. I saw it two nights ago, and it brought up a lot of feelings. I don’t suppose we could get together and talk about that one?”

“The Boxer. Uh . . . sure,” I reply, my words forming a kind of verbal shrug. The Boxer, already nominated for numerous film awards, is a small and powerful work of art about a troubled Catholic featherweight pugilist released after 15 years in prison for participating in an IRA bombing. Set in war-torn Dublin, it’s a stark, poetic work of art, that–on the surface–has little to do with God, religion, or spirituality.

But what the hell: If Conlon’s inner motor is revved up about this movie, who am I to argue? A former Catholic priest in Toronto and a renowned author of numerous books, including Geo-Justice: A Preferential Treatment of the Earth (Woodlake Books; 1992), Conlon is executive director of the Sophia Center, a forward-thinking theological school in the Oakland hills that emphasizes mysticism, feminism, and earth-based spirituality. He is also, it turns out, part Irish.

“Fifty percent Irish, to be exact,” he tells me the next day, waving me into a seat near the window in Sophia Center’s art-filled faculty lounge. “I guess I have a genetic connection to the film. I think it would have moved me anyway.”

A sprinkle of rain splatters softly against the window. Conlon glances out briefly, then turns to face his guest.

“I was struck by many things in the film,” he begins. “The oppressive feeling of being in Dublin, the guard towers in almost every scene, looming there over everyone. It reminded me of being in the little village of Monthill, South Arman, in 1992. They have what they call ‘Cemetery Sunday’ in Ireland–it’s a mass, a Eucharistic celebration, held in the cemetery, a very Irish thing to do. The Irish love cemeteries.

“I remember standing in that graveyard, looking up, and seeing these large turrets, several of them in all directions, with British soldiers looking down on us all. Their guns seemed to be aimed at us all the time.” He shakes his head.

“The other thing that struck me–there’s the whole Protestant vs. Catholic struggle, right?–was how religion can be such an energizer for destruction, even death,” he continues. “When I was living and working in Toronto, York University did a research project on racism. I consider the Irish question to be a matter of racism: North, South, Protestant, Catholic–it’s an issue of racism. What the research project uncovered was that the people who are the most racist are the people who are the most religious.”

Noting my unsurprised reaction, he grins, adding, “What that revealed to me was that religion can energize any perspective.

“One of the things we talk about here at Sophia,” he continues, “is the idea that everything that is created is different. There is no duplication in the universe. Thomas Aquinas said that God cannot replicate herself or himself in any one expression, because if that were true it would be God becoming God. So everything that is created is some unique expression of divinity.

“And yet humanity, as a species, has the most trouble of any species I know in accepting differences. At the root of us is this deep-seated resistance to embracing difference.”

“I’ve often wondered,” I reply, “how two people could sit in the same church, listen to the same lessons, sing the same hymns, and yet one might be inspired to an act of forgiveness while his neighbor might go out and commit some act of judgment or revenge.”

Conlon nods, stopping to consider this. “When I was in Canada,” he finally says, “there was a little town called Lucan, the home of a family called the Black Donnelleys. They would go to communion every Sunday, and they would literally hit each other on their way to church. If you go out to the cemetery there, which of course I’ve done, and you look at the graves of the family members of the Black Donnelleys, there are bullet holes in all the headstones.

“You know why?” he asks rhetorically. “They shoot at each other’s graves! Here they are, taking Holy Communion, and with the same breath they are hating one another with all their hearts.” He laughs softly. “So,” he sighs, still smiling, “I don’t know the answer to your question.”

The drizzle outside, after a brief cease fire, has resumed its attack on the window. “There’s something almost bipolar about the Irish psyche, isn’t there?” Conlon muses. “My father was a classic Irishman, in that he was that very Irish mixture of both pathos and passion. One minute, he’d be very harsh and angry, and then he’d sit and watch some sentimental movie on TV and suddenly the tears would just stream down his face.

“It’s that marriage of fierceness and pathos,” he concludes, “and it’s everywhere in Ireland. It’s imbedded in the culture, and in their lives, couched in harsh rigidity.”

From the January 22-28, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.