At some level, praising a movie for the quality of the acting alone is like praising it for its photography—it’s a way of saying it’s less than a sum of its parts—and the history of the Robert Duvall star vehicle (whether it’s called The Apostle or Assassination Tang) demonstrates why great character actors are rarely sufficient as lead actors. That same way of holding the screen in two or three small moments, the dynamics of what a character actor does, how he gets in and holds up a scene—all of that can be monotonous in a full-length film. Get Low‘s hushed direction by Aaron Schneider, which tells you This is important, this is like Faulkner, casts a spell, but it’s some kind of numbing, tranquilizing spell; the film can’t unstir itself from the level of an anecdote.

In the 1930s South, a hermit named Bush, with a beard that would do a Civil War general proud, emerges from his decades of solitude. He drives his mule cart into a nearby small town and makes plans for his funeral, the point being that he intends to have the funeral while he’s still alive. He finds no trouble with this idea from the local funeral-home director (Bill Murray), who expands on the event to bring music and a raffle; part of the draw will be Bush telling the secret that made him hide his face in the woods for so many years.

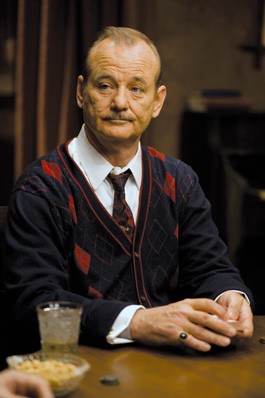

Murray, wearing a suspicious-looking mustache, fur-collared suits and a horseshoe pin, is the film’s saving grace. He has the true comedian’s solitude, and his driest lines resound like terrific jokes—the wince at boredom and a consoling flask in the pocket. One loves him and turns a blind eye to his anachronistic-as-hell dialogue as he mentors a younger salesman, Lucas Black. If it was always Gene Hackman’s aim to “play common men uncommonly,” Black gives an example of a man playing a common man commonly.

An intelligent, atmospheric Cold War thriller in the best tradition of LeCarre and Charles McCarry, and directed by Christian Carion, Farewell is based on a real-life case. Moscow, 1981: Pierre (Guillaume Canet), a French technocrat, is mistakenly approached by the gregarious Gregoriev (eminent Serbian director Emir Kusturica). This Soviet officer, sick of the hidebound government of the U.S.S.R., aims to help push it over from the inside by passing on important information to the West.

The Russian believes the Frenchman must be a spy of some sort, and is surprised to find out that Pierre has almost no connections with the secret service. Pierre’s government asks the amateur spy to carry on, and a friendship develops. Gregoriev takes his reward in Champagne and French books, and in confessional time: a spy who lies to everyone has to have someone to confide in, occasionally.

Farewell’s art direction is immaculate; Carion aims to take us on a trip to the vanished U.S.S.R., dwelling over the frightening Martian/Gothic towers and neon-green corridors. And in the rural scenes, the director proves why you could love that country while fearing its government. (The worst winters sometimes mean the best summers.)

The detours to the halls of Western power are a little more problematic. It’s a treat to see Fred Ward again. Ward’s imitative powers are so strong that his Ronald Reagan both looks right to the last twitch and is easily recognizable from across the room; however, Farewell‘s interpretation of that lucky but foolish man is fairly limited. (Perhaps it’s payback for every time we’ve Clouseauified French politicians.) Philippe Magnan’s dour Mitterand is far more knowing. A dash of Willem Dafoe, as a CIA intelligencer, ices the film nicely, and anyone who loves actors will relish the way Dafoe pronounces the phrase “serious problems.”

‘Farewell’ and ‘Get Low’ both open on Friday, Aug. 13, at the Rialto Cinemas Lakeside, 551 Summerfield Road, Santa Rosa. 707.525.4840.