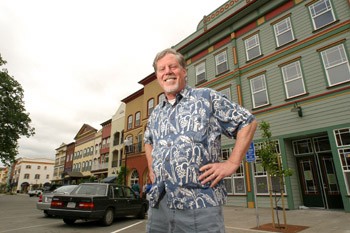

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Mr. Downtown: Developer Orrin Thiessen is changing the face of Sonoma County.

The There There

How developer Orrin Thiessen is single-handedly remaking North Bay downtowns

By Laura Hagar

The first hint that Orrin Thiessen isn’t your run-of-the-mill developer is that he describes his work by quoting Gertrude Stein. “Putting the there there,” is how Thiessen characterizes his company’s downtown redevelopment projects. He’s already remade the downtowns of Graton and Old Town Windsor, and has plans on the boards for Cotati, Occidental and the tiny West County burg of Forestville.

Skeptics say the fact that no one has raised any questions about the advisability of handing over the architectural future of Sonoma County’s collective downtowns to one man is a testament to two things: the public’s disaffection from the planning process and Thiessen’s blitzkrieg approach to redevelopment.

There is, of course, another possibility: maybe Orrin Thiessen is just the right man for the job.

I met Thiessen at his office in Old Town Windsor on one of those crystalline blue winter days that make one wince for the sheer beauty of Sonoma County. On a day like this, even Windsor–with its big-box malls, cookie-cutter subdivisions and trailer parks–looks blessed by the gods.

The phrase “Old Town Windsor” is itself a bit of a misnomer. Although there are a few old buildings left–the Presbyterian Church and a scattering of rundown 19th-century houses–Old Town is, by now, almost completely new. The heart of this new Old Town is the Windsor Town Green, a vast, mostly undeveloped expanse of grass, its young flowering plum trees and modernist fountain dwarfed by the giant heritage oak trees on the western end of the park.

The town’s unremarkable civic center–a white and beige ’70s-era police station, library and town hall that used to be a junior high–is almost invisible on the green’s northern edge. Windsor Vineyards’ equally beige corporate headquarters sits on the east side of the green. In comparison, Thiessen’s Town Green Village, with its dense and colorful faux Victorian architecture, almost vibrates on the southern and western edges.

Thiessen’s business offices are in the Town Green Village, the limited-liability partnership that runs every aspect of the Town Green Village project, located around the corner from the green in an attractive white building that looks like a late-19th-century hotel but is actually of new construction. The developer also owns Thiessen Homes, the project’s lead builder, though in typical developer style most of the work is subcontracted out.

Thiessen himself is a big man, over 6 feet tall, with a short shock of graying blond hair and the wind-burned skin of a sailor crinkling around handsome hazel-blue eyes. Walking around the development in his wraparound mirrored shades, he looks the part of the slick developer a little too well, but there’s something indefinably endearing about the man. He’s unpretentious, boyish despite the gray hair, and his enthusiasm as he shows off his massive new project is infectious.

Town Green Village is the largest mixed-use development in Sonoma County. Thiessen began the six-phase project three years ago. Phases one and two are located on the green and feature retail condominiums on the first floor and two-story residential condominiums above. Some of the later phase projects, just a block or so away, will offer professional offices below, residential housing above. A handicapped-accessible senior housing project is part of phase five. Ultimately, the entire project will create 250 new homes and 80 to 100 new businesses.

Thiessen allows no chain stores in his developments. “We want to provide an attractive alternative to mall shopping,” he says. Right now, there are several small restaurants (Vietnamese, Mexican and haute Californian), a couple of coffeehouses and home-decor stores, a children’s clothing store, a children’s bookstore, a jewelry store and a florist. The large, old-fashioned candy store, called Powell’s Sweet Shop, is a marvel and usually the busiest business on the block. The owner lives in the condo above the store.

Windsor’s Old Town began as a redevelopment project. In the mid-’90s, with an environmental majority on the city council, Windsor developed a separate general plan for its downtown. Using redevelopment and open-space monies, the city fixed the streets, put in underground utilities and built the town green. They also bought several parcels to the south of the green and started shopping around for a developer.

Under the leadership of Mayor Debora Fudge and progressive councilmembers, Windsor had a clear vision of what it wanted for its downtown: a large, mixed-use condominium project. Thiessen was one of the few developers in the area with significant experience with mixed-use and an enthusiasm for condominiums.

“It was a great relationship from the very beginning,” Fudge says. “Orrin says we made it easy for him because we knew exactly what we wanted. But he also made it easy for us because he wanted to build what we wanted to have.”

Thiessen is also an incredibly fast builder. “I think the town was amazed and pleased by how fast we were able to do this,” he says. “But part of the credit belongs to them. From the very beginning, we’d have meetings with city staff, and they’d ask, ‘How can we get out of your way?’ In some other towns, it’s like they have meetings to figure out how they can get in your way.”

In terms of scale and cost, Town Green Village is leagues beyond anything Thiessen has ever done before. “It was definitely a big step up,” he admits. “But we had a long track record of successful projects, and the city knew that. We’d done some small subdivisions. We did Graton’s downtown, and then in Windsor we did a mixed-use project called Star Station and some tract homes. The largest project we ever did before this was a 35-home subdivision in Sonoma. That was a $12 million project. Town Green Village is a $120 million [project] and counting.”

Thiessen ended up buying the parcels on the south side of the green from the city, as well as several other parcels on the surrounding blocks–23 parcels in all. “You’ve got to understand,” he says, standing at the north end of the town green, “this was a really blighted area. Right here where we’re standing was a real ghetto. It was probably one of the worst neighborhoods in Sonoma County, as far as aesthetics go. Nothing was really worth saving. We tore down the houses, built new buildings. That’s what redevelopment is designed to do.”

Thiessen isn’t deaf to the implications of such statements, which connote an “out with the poor, in with the rich” (or, in this case, “middle-class”) flavor. But philosophically, he’s got different fish to fry. He is a passionate advocate of New Urbanism, a philosophy of urban planning that emphasizes human-scale development, mixed residential and commercial areas, and walkable downtowns focused around a central plaza.

“What we’re trying to do here,” Thiessen says, “is to build a village from the bottom up, because that’s where people want to live nowadays. They don’t want to live in some vast, impersonal subdivision or some honeycomb-like apartment complex, where nobody knows their neighbors and you have to get into your car to do anything at all. They want to live in a village. If you look at Sonoma County, you’ll notice that the most popular and attractive cities, the ones where people really want to live, have real downtowns, often old Spanish plazas like in Sonoma or Healdsburg. A downtown provides a sense of coherence for the city as a whole and acts as a central gathering place.

“Another aspect of New Urbanism is smart growth,” he continues. “The reason I call it ‘smart growth’ is that I can build on 10 acres what would probably require 50 acres if you developed it using a traditional sprawl model with tract homes and shopping centers. Smart growth conserves land, our most precious resource. Urban sprawl is a big problem in California, especially in Sonoma County, and smart growth is one of the answers to urban sprawl.”

Now all the rage in urban-planning circles, New Urbanism was inspired in part by Jane Jacobs’ 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a critique of the urban-renewal schemes of the middle of the last century. Jacobs praised the close-knit, urban neighborhoods of big Eastern cities–those homely, humble places where people worked and shopped just a stone’s throw from their front door and everyone knew everyone else.

Implicit in Jacobs’ critique is a reaction against the modernist aesthetic of the mid-20th century. As a result, the architecture of many New Urbanist developments harks back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although there are New Urbanist villages with modern or postmodern architecture, many of the most famous, like Disney’s Celebration, Fla., community, are nostalgic in feel. Thiessen’s Town Green Village is a case in point.

Development on the south side of the green consists of four very large buildings, broken up into smaller visual units by the use of false fronts. Most are Victorian or late Edwardian in style, though some on small side streets feature Spanish-inspired Period Revival architecture. The choice of colors is bright yet pleasing: sunburst yellow, brick red, navy and forest green and an occasional purple.

There is, one has to admit, a certain Disneyland-like quality to the place. The newness of it all, the nostalgic architecture and the false-front design all add to this impression. From the street, and inside the stores and restaurants, the illusion of separate buildings is very real. To access the residential condominiums, however, you enter through the side of the building into a long central corridor, and from there the buildings look like what they are: big, modern structures.

There’s nothing faux Victorian about the condos. They’re modern in feel, with open kitchens dividing the large downstairs space into two separate areas. The bedrooms are upstairs. The three-bedroom unit I saw had two bedrooms in back and a large master bedroom in front, overlooking the green. The one nod to Victoriana is the New Orleans-like wrought-iron balconies looking out over the green. Large enough to fit just one person, they seem to have been made for parade viewing. One wants to stand on them and wave small flags for some obscure long-lost holiday, like Armistice Day.

Thiessen is the Town Green Village’s main designer. He designs all the buildings and chooses all the colors himself. “I’m the planner, the designer, the builder. My company is the developer, and we’re also the real estate company–everything. Total control. It would be really difficult to do this if you were a developer hiring an architect, hiring a builder. It would be hard to make any money.”

Thiessen has no formal architectural training, a fact that doesn’t worry him at all. “How much does somebody learn in a couple of years of architecture in college?” he asks. “Not very much. Where you really learn things is on the job. I’ve been designing and building buildings for 30 years. It’s just an experience thing.”

For his exterior designs, at least, Thiessen takes his inspiration from historical photos of Sonoma County. He has rebuilt several of Windsor’s long-gone historical buildings, including the Reimann House, a 19th-century hotel, and the McCracken Building, Windsor’s old general store. Another building was inspired by the Occidental Hotel, which collapsed in the 1906 earthquake. “I saw a picture of it in a book, liked it and decided to rebuild it,” Thiessen says.

“This building here,” he says, gesturing to a massive building west of the green, “is going to have Northern European-style architecture, which is something I’ve always liked.” The building has large octagonal cupolas on each corner. Their unfinished roofs sit like grounded flying saucers in a vacant lot across the street.

One hates to quibble with the architecture of a project like this, in part because Thiessen is trying to do something different and important, and also because it’s so much better than what was here before. Kent Patty, a 22-year-old Windsor resident I found lounging with friends on the green, remembers what Windsor was like before Thiessen arrived. “There was a McDonald’s and a library and a whole lot of nothing,” he says. “Before the town center was in, this was just a weedy field. I think Windsor’s town center is awesome, especially for families. It provides a real sense of community.”

Doug Eliot, president of Workforce Housing Associates, a developer of affordable housing based in Petaluma, is equally enthusiastic. His company is building affordable-housing condominiums around the corner from Town Green Village. “As a competitor of Orrin Thiessen’s who is working in the same town, I think that the guy is an absolute visionary. He’s really walking the talk. Everyone talks about in-fill and smart growth, but Orrin is actually doing it.”

Steve Orlick, chair of the department of environmental studies and planning at SSU, is guardedly optimistic about the development as well. “In a lot of respects, it’s very impressive. It’s actually a rather bold effort, considering that cities and lenders usually prefer more standard, less imaginative developments. Have I seen false-front developments that are better? Sure, I have: the Swenson Building on the square in Healdsburg is one. It fits right in with the existing surroundings and doesn’t have that sort of artificial look. You could say that’s the difference between good design and a nice effort.

“But you have to look at the larger picture. Orrin Thiessen is doing an important thing with Town Green Village. His idea of building a mixed-use development around a central plaza is consistent with New Urbanist design principles. There aren’t a lot of examples of this type of development locally, so he’s really starting a track record that, if he’s successful, others can build on.”

But does Town Green Village really work as a New Urbanist development? It’s still a little early to tell. After all, only one of the projects’ six phases has been completed. Still, Orlick has a few concerns. “One of the main ideas behind mixed-use is that people don’t have to get out of their cars to get the basic things they need everyday. They can walk to essential stores that are close by. One potential shortcoming of Town Green Village is that the kind of upscale retail development they’re promoting isn’t what people living in that neighborhood are likely to need on a daily basis. They’ve got some cafes, and that’s good, but they don’t have basic things like a grocery store or drugstore or even a real bookstore. That’s the kind of development you need close at hand to get people out of their cars.”

Getting people out of their cars is a problem that most New Urbanist developments struggle with, Orlick says. Town Green Village, situated on a major rail line, should have a leg up, if Sonoma’s long-promised rail system ever come to pass. The site for the proposed rail station is located directly across the street from Thiessen’s office.

“The real test of the development isn’t what’s happening right now, but what will happen once the rail is in,” Orlick says. “Will people be able to get off the train at the end of the day and walk home, picking up what they need along the way? Can they pick up their dry cleaning or get a quart of milk?”

Mayor Fudge says rail advocates had hoped to get a quarter-cent sales tax on the countywide ballot by this year in order to get a train up and running by 2007, but that the poor economy and cuts to more essential services, like fire and police protection, made that politically impossible. The city is still committed to building a train station, though.

In the meantime, in order to create the population base needed to support a retail center like Town Green Village, the city is authorizing several denser condominium developments in the downtown core. Some of these will feature smaller and more affordable units than those found in Thiessen’s development and will be built by traditional affordable-housing builders like Burbank Housing Development Corporation and Workforce Housing Associates.

Thiessen has never claimed to be a developer of “affordable housing.” Though he sold the first Town Green Village condominiums for $279,000 two years ago, the going price for those same three-bedroom condos is now $390,000. Condo prices range from $190,000 for a very small two-bedroom to $439,000 for one of the larger three-bedrooms overlooking the green. Most are priced between $300,000 and $350,000.

Thiessen doesn’t necessarily see affordable housing as particularly compatible with mixed-used downtown development. “Downtown areas have the most expensive land and the most ornate buildings–neither are a good foundation for affordable housing. A lot of people just can’t get this through their heads. They want affordable housing in their mixed-use downtowns. Well, unless it’s heavily subsidized by the government, it’s just not going to happen.”

In early February, Windsor debated passing a “workforce housing linkage fee” that would require developers of commercial property to pay a fee toward the development of workforce housing. Fudge argued passionately for the measure, but during the public-comment portion of the evening, Thiessen spoke against it–or at least against applying such a measure to his development.

“I’m not against the linkage fee per se,” the Windsor Times reported Thiessen as saying, “but the ultimate linkage is mixed use. It would be ludicrous to take a fee on top of that. If you’re going to pass a fee, don’t hit us with it because it will really hurt the downtown development.”

Before the evening was out, the linkage fee was defeated.

How did Orrin Thiessen become the developer of choice for Sonoma County’s downtowns, and where will he be working next? Though he has lived in the county for more than 30 years, he isn’t a native. He grew up in Southern California, in Ventura County. His father was a machinist and an entrepreneur who built his own large machining company and retired at 43.

After retirement, Thiessen’s father took up building and development, almost as a hobby, and Orrin learned his carpentry skills working on his father’s projects over the summer. After a stint in a junior college down south, Orrin went to SSU, majoring in biology. In his senior year, as a part of his thesis project, he built a cottage completely out of recycled materials and enjoyed the experience so much that he decided to leave school a few months short of graduation and go into construction. “My parents weren’t too happy with me,” he says drily. But construction proved a good game. In time, he married a fifth-generation West County girl and set to work building homes on speculation in his wife’s home town of Forestville.

(I should mention, by way of disclosure, that I actually live in one of the spec homes Thiessen built in Forestville in the early ’90s. We bought the house as a compromise between my husband’s taste and mine. I like old houses with lots of character; my husband, an engineer, likes new houses with lots of insulation.)

Thiessen’s first experience with downtown development was Graton, a stone’s throw from Thiessen’s own home in West County. The pattern of redevelopment that Thiessen established in Graton is one he’s followed ever since. He and a partner basically bought Graton’s entire downtown–nine parcels in all–and set to work fixing it up. It was also Thiessen’s first experiment in mixed-use development. Many of the buildings in the town utilize the concept of “horizontal mixed-use”–that is, retail in front, residential in back. He renovated a few of the historic buildings, but for the most part, he tore down what was there and built new, drawing inspiration for his designs from photographs of Graton at the turn of the century.

Over the next few years, Thiessen plans to build projects in Cotati, Occidental and Forestville. In Cotati he plans to build a three-story mixed-use building just north of the hub. He has just purchased the Harmony School land for development in Occidental. In Forestville he plans to break ground in two years on another mixed-use development–45 residences, 15 to 20 new businesses and a town green–on the much-disputed Crinella property downtown. Though small in comparison to Town Green Village, it’s a huge project for Forestville, a rural burb of 5,000 with a downtown that is currently little more than an underpatronized commercial strip.

How does Thiessen characterize his plans for Forestville? “We’re going to put a there there.”

From the April 21-27, 2004 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.