Alexandria Brown isn’t a foodie, but she wrote this year’s most compelling North Bay book on food. In fact, Lost Restaurants of Napa Valley and Their Recipes, released in April by The History Press, was written while its author lived in a kitchenless apartment. In it, Brown—a historian—uses restaurants-past as a lens through which to tell stories of the immigrant and people-of-color communities that shaped the esteemed culinary region.

At first, Brown—who has master’s degrees in library science and U.S. history—wasn’t eager about her press’s proposal to write about restaurants. But she did a bit of research and soon got excited about the project.

“I found all of these people of color, immigrants and women who were doing really interesting things with food but whose stories had never been told or had been white-washed,” says Brown, who is a Black woman raised in Napa.

While focused on Napa, Lost Restaurants is also a book that traces how “exotic” and “foreign” foods become “American” classics.

Several of the book’s chapters focus on a specific cuisine. “Chili Queens and Tamale Men” tells the stories of Mexican-American cuisine in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The chapter “Chow Chop Suey” explores three 20th-century Chinese restaurants that specialized in the wildly popular dish of the time. Brown’s book couldn’t tell the stories of Chinese food and local restaurants without also telling the story of Chinese immigration to Napa, xenophobia, racism and pervasive “model minority” myths.

Brown likens her book to Padma Lakshmi’s new Hulu series, Taste the Nation.

“I feel like we’re doing similar things and our audiences are similar,” she says. “We’re both looking at history, food, race and immigration. We’re mixing these topics together in one big pot and doing it in a way that’s approachable but educational at the same time.”

It’s worth noting that Lakshmi’s show began as a research project on immigration. According to The Atlantic, food was later chosen as a way to become more acquainted with the communities Lakshmi was investigating. Similarly, the intimacy and universality of eating are often what make Brown’s book—including its tough truths about racial inequity—palatable.

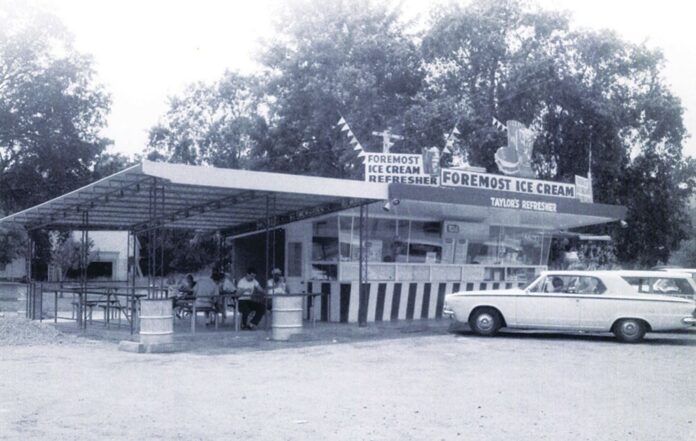

Brown says older locals will delight in the book and may remember going out as children to some of the mid-century restaurants spotlighted, such as the drive-in Taylor’s Refresher. The cover of Lost Restaurants, with its signature ’50s diner-esque font and vintage photographs, evokes this nostalgia.

One photo on the back cover is meant to bait some readers who may expect a different book.

“Reagan announced his gubernatorial campaign at the posh Aetna Springs in Pope Valley,” Brown says. “I really like the idea of grumpy conservatives looking and thinking, ‘Ooh, Reagan! Yes!’ Then they’ll open the book and find out that it’s all about immigrants and Black and Indigenous people of color.”

What Constitutes a Restaurant?

Restaurants, as we think of them today (or as we thought of them throughout our lifetimes until a global pandemic exploded this March), are a fairly recent concept.

As readers will learn, the French word restaurant initially described a rich meat broth that would restore one’s health. Later, it came to refer to the places that sold such broth.

In 19th-century Napa and other Western towns, restaurants weren’t places you went out to eat at for a fun time.

“You ate where you could get food because you weren’t cooking because you were a transient man with no house and no wife or a woman who was working in a hotel,” Brown says.

With this in mind, Brown’s definition of “restaurant” was broad—covering any place that prepared and sold food to the public. That allowed her to talk about bars, resorts, hotels and wholesale vendors.

“We had a lot of home tamale makers,” Brown says. “Latinx women who were Californiana descendants who would make tamales and sell them to bars and markets.”

Most of Brown’s research began with old newspapers and their advertisements, sometimes as spare as a note saying, “So-and-so is now selling tamales at this local grocer!” Many local newspapers are digitized through the Napa County Library, but Brown’s research also included a trip to the Huntington Library to look at some original Napa newspapers from the 1850s.

From these leads, she could often learn more about restaurateurs by digging into census data and genealogy research to piece together fuller stories of her subjects’ lives.

However, she sometimes met dead-ends.

“Old newspapers tend to be fast and loose with facts,” Brown notes.

She was fascinated to learn that two men of Japanese ancestry briefly owned a restaurant on East First Street—near where Oxbow Market is today—in the early 1900s. Their names, listed in two old ads, were spelled differently each time. Brown even looked in the Japanese internment database, but could find no record of them. Since their story is unknown, it doesn’t appear in Lost Restaurants.

Brown wishes she knew more about these men.

“We don’t talk about Black people in Napa, but we really don’t talk about Japanese people pre-internment here,” she says.

Though records of most early Napa restaurants aren’t difficult to find, little has been written about them. Unless someone was really famous, people didn’t write in-depth stories about restaurants of the time.

The Recipes

Brown’s book contains 18 recipes, though not all are user-friendly. Readers should keep in mind that, in many cases, people cooked over fire and their recipes didn’t offer cook times or temperatures.

“There’s a wedding cake recipe that has absolutely no cooking instructions in it and I wouldn’t probably recommend attempting it,” Brown says.

There are two chop suey recipes presented—one from 1902 and another from 1931.

“Every recipe would be like, ‘This is the official recipe for chop suey—this is exactly how they make it in China,’” Brown says, “and it would be completely different than the next recipe that made the same claim.”

Like many recipes of the time, readers are told what ingredients to combine (mostly animal offal), but not how much of them.

That said, Brown tasted the parmesan polenta recipe from Caterina Nichelini, the late founder of the still-existent Nichelini Family Winery (established 1895), and it stands the test of time.

Brown still hasn’t prepared any of the recipes herself, but would love to hear from adventurous readers who do. She can be reached through her website at bookjockeyalex.com

Watch the author read from Lost Recipes of Napa Valley and talk more with Chelsea Kurnick about her book here on YouTube at https://bit.ly/3fvwptP.