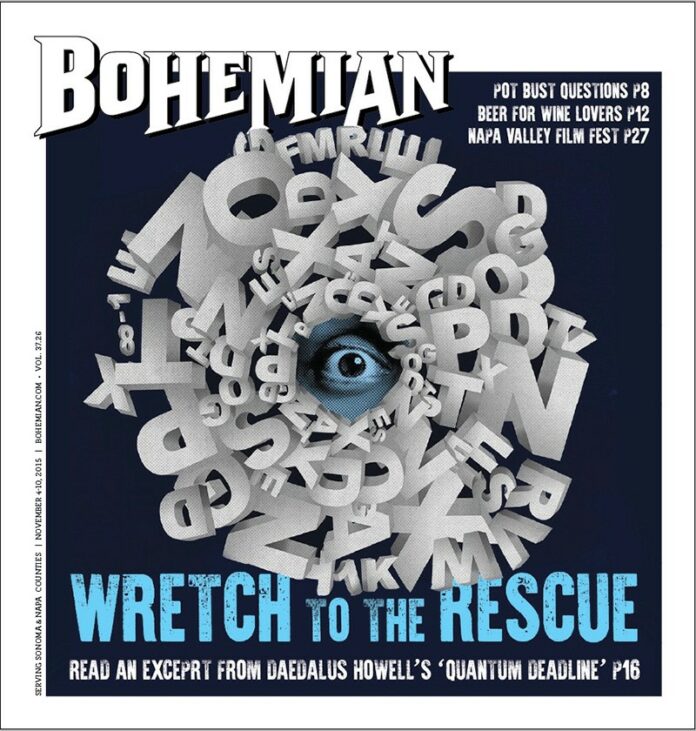

Daedalus Howell’s novel Quantum Deadline:

The Lumaville Labyrinth is hard to categorize. Let’s call it a noirish, sci-fi-lite detective story with a heap of self-parody that’s by turns poignant, witty and comic. It’s set in an alternate version of Petaluma. The novel features a character named Daedalus Howell as a sad-sack journalist in a cheap suit/superhero costume trying to navigate life in the digital age and a darker vision of Petaluma called Lumaville. In addition to sharp writing, the book’s take on the state of journalism and Petaluma’s reinvention is one of its strengths.

“Petaluma is going through a radical transformation,” says Howell. “It’s having its moment. It’s transforming into a Xanadu for a certain kind of post-metropolitan creative professional. Which makes it ripe for parody.”

With humor and verve, the novel takes up some of the experiences and struggles within Howell’s personal and professional life. He says he likes to explore “the liminal space between truth and fact” as it relates to himself.

“I was able to explore the worst parts of myself and expunge them,” he says of the novel. “I’m already a bit absurd, so I just thought I’d embrace it.”

Howell is currently writing a sequel, but for now enjoy this excerpt from the first chapter of Quantum Deadline. If you want more Howell, and I bet you will, he will read from his book on Nov. 20 at 7pm at Outer Planes Comics and Games, 519 Mendocino Ave., Santa Rosa.

—Stett Holbrook

[page]

Early in my career, I was a green reporter who wrote purple prose that read like yellow journalism. But they printed the paper in black and white so no one ever noticed.

Now I was just a hack, one who needed a story and needed it bad. The problem, as always, is that I’m not the type to make my own breaks. I’m not inclined to write a bogus memoir, say, or parade as a pillhead or claim to be the last, lone believer in my generation. I’m also not opportunistic enough to know a good thing when I’ve got it, so whatever it is, it won’t make it into print—or pixels—let alone a bestseller list. Even if it did, the editors wouldn’t believe it. Such is the hazard of being in the truth business, not the fact business.

Forgive me. I buried the lede . . .

You see, back in J-School, in the ’90s, my future colleagues and I knew nothing of the then-nascent Internet and the havoc it would wreak on our prospective industry. Now there’s an entire generation that has never read a printed newspaper. And they’re the ones running the papers. Or what’s left of them.

This is how I found myself on the lifestyle beat for a startup that required endless filing of snark and crap that met certain considerations of “keyword density” and adhered to the house style of punchy prose that was neither punchy nor prose by any definition of contemporary letters. IMHO. For the past five years, the work had been winnowed, watered and weighed down in equal measure. For the past five years, I’ve been in psychic exile. For the past five years, I’ve been leaning on a pseudonym to make the rent because . . .

I also buried an intern.

This is the truth. When you fail to talk your newsroom intern out of jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge, prepare yourself for the following: Your intern will be dead, your career will be over and your newspaper will fold. And not into a paper hat.

That’s really how I became a small town newspaperman without a town or a newspaper. I’m sure some even questioned whether I had the moral ground to call myself a man.

With some modest triangulating on Google, it could be known that I was the writer whose words—my stock and trade—had utterly failed to talk a young man out of taking two steps back onto the bridge’s pedestrian walkway and into the rest of his young life.

“Is it going to get better, the newspaper, life, all of this?” he spat against the wind as it whipped his hair against his 21-year-old forehead.

“No. It’s only going to get worse.”

“Then why do we do it?” he asked.

I didn’t have an answer. Or, I did, but it wasn’t the right answer. He shifted his grip and the sweat from his palms darkened the rust-hue of the girder. I improvised.

“Deadlines . . . ?”

This much is certain: It was not the answer he was seeking. He let go and in one glib moment, with no foresight and no hindsight of which to speak, changed both of our lives forever.

There’s more, but we’ll get to that. What’s germane is from that moment hence I’d been searching for a story—a new story that would make my past and failures a footnote to the shiny future I’d lost, that my intern lost, that everyone lost. Really, my new story needed to be an old story: a redemption tale, as they say in Hollywood; one with enough truth and triumph to clear my byline so that, among other advantages, I might use it again.

I found the story. Or, I could get cute and say the story found me. Apparently, that’s an antimetabole. Some day I might look it up to prove it. In the meantime (not to fracture the fourth wall into constituent fractals of meaning) the story begins, as these things do, in a mirror.

There’s a kind of guy who can wear a cheap suit well and I like to pretend I’m him. Frankly, I had no choice, especially after I burned a cigarette hole through my last good blazer and I have an image to maintain. I am among the last of a dying breed of lifestyle reporters, feature writers who, as one neckbearded editor put it, “grok the grub and grog,” which always sounded to me like the sounds of someone being strangled. But it’s a living. Or was. Hence, my pitstop at Gemelli Bros.

The discount suitery was owned by a pair of oily identical twins squeezed into double-breasted suits who called themselves Tweedle Deep and Tweedle Dump in their local television ads. Tweedle Deep, I think, was marking up my new coat with chalk when it happened.

“You like a little room in the chestal area?” he asked, tugging at the coat’s hem. I stood still in the three-way mirror like a human mannequin if they made them in my size, 44 long, wide in the shoulders, taller than most, which made the gut passable if I never exhaled.

“I’ve gotta fit a reporter’s notebook in my left breast pocket,” I said. “And a pen.”

The man grunted and swiftly drew an X over my heart.

“I never met a newspaperman before,” he said. He was being facetious, as if “newspaperman” was what a paperboy grew up to be.

[page]

The phone rang and the man trundled off through the maze of suits crowded on their racks like delicatessen salamis.

In the mirror, I was surprised at how relatively good I looked despite the night before. I outstretched my arms and the black coat opened crisply like an umbrella. I surmised from the inexpensive blend of polymers that the coat was waterproof.

The fat clothier brayed into the phone. His tone was heated. I entertained myself by maneuvering the hinged mirrors, flanking the one in the middle so that my reflection went from triplicate to infinite. This is how I used to kill time when my mother dragged me to department stores when I was a kid. For that matter, it’s how I kept from losing my mind when my ex took me on forced marches through the junior’s department whose trendy tops and shrinking bottoms she could still pull off in her thirties.

I began to entomb myself in the mirrors, creating hundreds of images of myself—rumpled, debauched but serviceably handsome to a certain type of woman. One whose standards have been systematically lowered by being born Gen X and coming of age under the sign of Slack.

An intruder entered my chamber of narcissism. A small quizzical face beamed back at me through the corner of the left mirror. It was a boy of about eleven with dark hair and a tailored blue suit with a badge on the pocket.

He shook his head. I straightened, reflexively, as if he’d caught me picking my nose. I turned from my personal Escher print and spied him standing outside the store window staring at me like I was a ghost or he was a ghost or . . . I couldn’t take it.

I flipped him off.

I expected the kid to do the same back at me. Instead he shouted, “Down!” At least that’s what it looked like he said. I couldn’t hear him through the window. Besides, it sounded like a walnut had just been cracked upside my head. The mirror behind me shattered.

“You fuggin’ asshole!” boomed through the coat shop, punctuated with another shot. This one sounded like a fist deep in a down pillow.

I was on the floor, belly down, atop saber-length shards of broken mirror. My knees had buckled autonomically. Was I shot? I rolled behind a rack and patted myself down. Not even a scratch from the glass. I looked up and saw my tailor clutching his gut.

“She’s my wife!” the shooter said. His tone was one of defeat.

Tweedle Dump kept the gun trained on his twin brother. Two thoughts crossed my mind simultaneously: (a) They should have incorporated some of this sibling rivalry shit into their TV commercials, and (b) Where was the kid? I belly-crawled to the coat rack as another shot rang through the shop. Tweedle Deep wheezed, “Fuck you too.” I peeked through the size 34 slacks. He had a small pistol weighing in his pudgy hand. He dropped to his knees as his porcine twin glowered back, his white shirt now a rising tide of blood and bile.

“That’s not going to come out,” Tweedle Dump observed before also falling to his knees, his bulk jiggling like a massive water balloon. After a beat, both Gemelli twins collapsed onto the beige berber carpet in a puddle of oily, brown blood.

A store clerk with pasted-down hair wandered into the front door and calmly observed dead orcas draining on the floor. He called 911, but not before calling his girlfriend to tell her to stay in bed, because he was taking the day off. He looked at me and shook his head. “It was going to happen sooner or later. Lucky you didn’t get hit. Them brothers was as blind as shit.”

“I’m fine,” I said as I unfolded back onto my feet. “There was a kid in the window, you see him?”

“I didn’t see a kid. If he was here, he was gone when I got here. If he’s a neighborhood kid this ain’t nothing he hasn’t seen before. Had the good sense to run,” he said matter-of-factly. “Probably home doing instant replays on his video game machine.”

When the police arrived, they cordoned off the crime scene with yellow tape until it looked like a cat’s cradle. They took pictures and proceeded to fill paper cups with coffee from a large press pot.

“That press pot is the most important part of our forensics kit,” explained Detective Shane. She was black, rounder than perhaps she cared to be and appeared young for her rank, which is to say, younger than me. “You put shit in it?”

I looked at her blankly and she handed me a cup of black coffee.

“So, you say there was a kid? Did he witness the shooting too?”

“I’m not sure. It all . . .”

“Happened so fast. I know. Bullets are like that. Well, we put a car out looking for him and no one’s turned up. Should be in school anyway,” she said.

I nodded and sipped the coffee. The detective watched me sip.

“It’s good, isn’t it?” she said proudly. Our department has the best coffee in the East Bay.

“What’s your secret?”

“We give a fuck. That’s all. You just gotta give a fuck.” She folded up her notebook. “Listen, I’ve got your statement. You’re not a suspect, the security cameras confirm that. I might need you to come down to the station later for more details, especially if the kid turns up, but otherwise, you’re free to go.”

“Does it matter that I’m a member of the media?” I asked for no good reason. Maybe I wanted to seem in the game—that I wasn’t just a civilian. Shane gave me a once-over.

“In that jacket?” she quipped, then caught herself reflected in my eyes. “It’s really that bad for you guys, isn’t it?”

I nodded, “Just me.” But I knew my luck was beginning to turn and that kid who should’ve been in school was part of it.