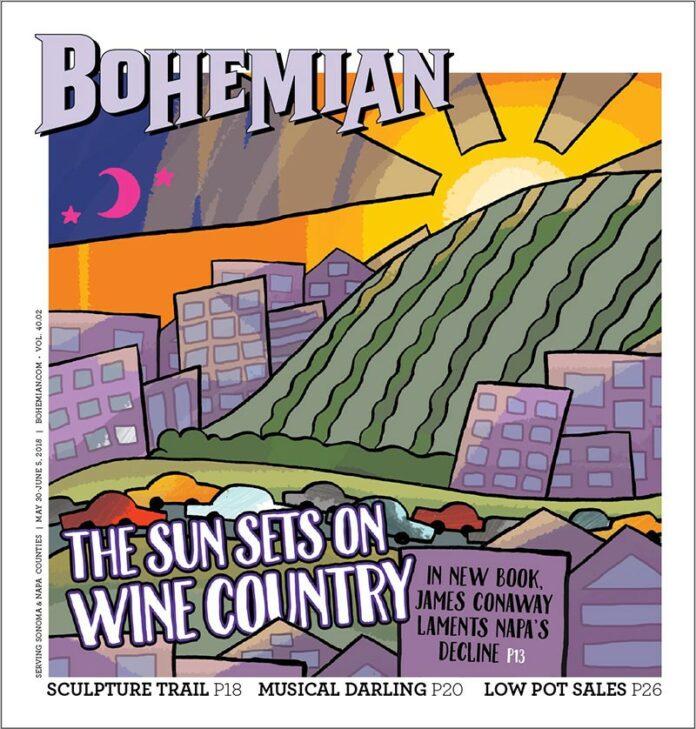

The traffic is horrendous, especially on weekends. The noise can be deafening on country lanes where big machines rip up the earth. Vineyards have spread everywhere, Pinot and Cabernet have never been more plentiful, and pesticides and herbicides have shown up in creeks and streams.

In a nutshell, that’s the Napa County story, though the Mondavi clan and the folks at Yountville’s Domain Chandon—which is French- owned—along with David Abreu and the notorious John Bremer, insist that they bring culture and civilization to a backward land and hand out millions to community groups. To be sure, Napa makes great wine. But at what cost to the land and to the people? That’s the question.

James Conaway’s muckraking tour de force Napa at Last light: America’s Eden in an Age of Calamity recounts the secrets, the backroom deals and the hillside devastation that has shocked citizens and persuaded some winemakers and grape growers to call for reform. The book arrived in stores in March, three months before the June 5 ballot on Measure C. Widely read, it has strengthened the pro-C forces, though it has also helped fuel the anti-C folks. Where Conaway’s books are concerned, there’s no neutrality. Indeed, his words can be intoxicating, especially when he writes about wine as the beverage that “sustains kings, poets, politicians, priests, lovers, idealists, the sick, the stricken, and all manner of rascals.”

Measure C—known as the Napa County Watershed and Oak Woodland Protection Initiative of 2018—aims to limit hillside development for grape vines and “protect the water quality of Napa County’s streams, watersheds, wetlands and forests, and safeguard the public health, safety and welfare of the County’s residents.”

Ironically, Conaway—arguably the author who has done more than any other single writer to raise awareness about the environment in Napa—can’t cast a ballot on June 5. Born and raised in Memphis, he divides his time between Virginia and Washington, D.C., though he often explores Napa County, where he has friends and some enemies too. He has been drawn to Napa because of its spectacular beauty, and also because he sees Napa as emblematic of California. In 2002’s The Far Side of Eden, the second in the trilogy, he writes that “Napa Valley was California in microcosm.”

In his latest book, he gives voice to the chorus of citizens who want to take back their county from what some see as the dominating influence of the wine industry. “To some, I’m a local hero,” says Conaway. “To others, I’m an enemy of the people.”

The battle over Measure C, which could have implications for vineyard development in Sonoma and Mendocino counties, has been a hard-fought campaign with its share of mudslinging. Misinformation, disinformation and outright lies have defined much of the campaign. So it’s not surprising that Conaway has been demonized in some, though not all, viticultural circles.

A dozen high-profile grape growers and winemakers support the initiative. They include Andy Beckstoffer, one of the largest landowners in the county, and Warren Winiarski at Stag’s Leap, which was one of the winners at the 1976 Paris tasting that put Napa Valley on the international wine map.

Opponents of Measure C have insisted that if it passes it will undermine private property rights and prevent future farming in agricultural watersheds. Vintner Stuart Smith, who created a website called Stop Measure C, says, “The initiative was written by two people and lawyers in a backroom.” Smith adds that you have to have “economic wealth” in order to create “effective environmental protection.” (See this week’s Swirl, p12, for more from Smith.) Conaway calls comments like Smith’s “environmental McCarthyism.”

Grassroots supporters of C have launched their own counter-offensive. In April, lawyer and Soda Creek Vineyards owner Yeoryios C. Apallas, filed a lawsuit that prompted the Napa County Superior Court to order the removal of false statements from the official voter information pamphlet. “I could not sit by while opponents deliberately misstated the facts to confuse voters into rejecting this important measure,” Apallas said.

Among the most blatant misrepresentations was one which claimed that “measure C will prevent homeowners from making even the smallest changes to their land.” That statement, and others like it, were removed from the pamphlet for Napa voters, though not all the misstatements were removed. Moreover, the campaign against the ballot measure agreed to pay $54,000 for the legal fees incurred by the “Yes on C” forces.

But the court ruling didn’t prevent the proliferation of “No on C” signs that dot the landscape and which insist that, if enacted, the law would lead to more traffic, higher taxes and negative impacts on farmers and agriculture.

The signs for and against the ballot measure haven’t surprised Conaway. Napa at Last Light completes the saga he began in 1990 with Napa: The Story of an American Eden and continued with The Far Side of Eden: New Money, Old Land, and the Battle for Napa Valley. In the second volume, Conaway notes that “tourists devour the thing they love.” Sixteen years later, he says Eden is now all but lost, though if Measure C passes, he believes it will help to restore some of the original paradise.

[page]

Reviewers of the book, such as San Francisco Chronicle‘s wine, beer and spirits writer Esther Mobley, have insisted that Conaway’s voice is now louder and angrier than it has been in the past. Attentive readers will also notice that Conaway is sadder than before about the triumph of money and power in the Napa Valley. One might subtitle Napa at Last Light, not “Grapes of Wrath,” but “Grapes of Sorrow.”

In the third volume of the trilogy, Conaway uses his skills as a writer of fiction—he’s the author of three novels—to create memorable, real-life folk heroes, such as the aristocratic, French-born global wine baron Jean-Charles Boisset, who owns dozens of wineries, including the famed Buena Vista in Sonoma. His wife, Gina, belongs to the legendary Gallo clan.

Some of Conaway’s sources are on the record, though not all. He calls one man “Deep Roots” and intentionally conceals descriptions that would give away his identity. He calls another source “the attorney.” Outing him would cost the lawyer his reputation.

Geoff Ellsworth was a willing and a candid source. A St. Helena council member, artist and supporter of Measure C, Ellsworth has lived in Napa County for 50 years. For decades, he watched the slow, steady chipping away of the forests, the privatization of watersheds and the spread of roads, vineyards, wineries, tasting rooms, event centers and estate homes. Like Conaway, Ellsworth decries what he calls the “erosion of democracy” in Napa. He worries that if the dominance of the industry goes unchecked in his hometown, it can happen anywhere in the United States.

On a hot afternoon, as I tour the valley with him, Ellsworth says that while he believes the ballot measure will pass, he also argues that “neither drought, nor flood, nor fire will keep corporations from gobbling up resources in Napa.”

As a kid and young man who grew up in St. Helena—his parents supplied equipment to the wine industry—Ellsworth assumed that Napa County would accept limits on tourism and stop the expansion of vineyards on steep slopes. He also assumed that citizens would decry the loss of habitat for endangered species like the spotted owl.

“We’re nearly at the point where advocating for clean water for everyone is beginning to look revolutionary,” Ellsworth says. “It looks like Napa is turning into the ‘valley of the oligarchs.'”

His friend and feisty ally, Kellie Anderson—who once worked for the wine industry as well as for the Napa County agricultural commissioner—describes some wineries as recreational playthings for wealthy owners and absentee landlords.

“Sometimes a vineyard comes with a Ferrari and a trophy wife,” Anderson says. “Meanwhile, watersheds are destroyed and citizens are screwed.”

Like Ellsworth and Anderson, Conaway wants to stop, or at least slow down, the runaway wine and tourism juggernaut before more of what makes Napa special is lost. “The time has come to say ‘No More,'” Conaway writes in his new book.

During a phone conversation in which his Memphis accent gives away his Southern roots, he says, “I like Pinot, though I can’t afford Napa Cab, which wine makers now call ‘rocket juice.'” (A bottle of premium Napa Cabernet can easily cost $100.)

Conaway is optimistic, but he can’t help but see doom and gloom. He wants things to be right, but he imagines they’ll go wrong. So he’s divided in his feelings about Napa, and both pleased and alarmed at what he sees in neighboring grape-growing, winemaking counties.

“Sonoma County still feels rural, and that’s good,” Conaway says. “But Sonoma will probably go the way of Napa. It’s just too damned attractive for big money.”

Indeed, whether C wins or loses, pockets of Napa’s beauty will endure. Is that enough?

Napa at Last Light ends with the sound of a screaming hawk and a prophetic view of a time when “many are likely to pass though these lovely mountains and will pause as they do now, nature-struck, all momentarily struck by the beauty of this place.”