Few landscapes connote dystopian waste like Richmond’s Chevron refinery. Razor wire circles the 2,900-acre complex—a gray metropolis of rusting train tracks, lake-sized oil drums and charred smokestacks that smolder like giant cigarettes. It’s difficult to look at the site without remembering the 93 air-safety violations the refinery’s been slapped with since 2008, or the black clouds that engulfed the smokestacks when a diesel leak caught fire last August, hospitalizing 15,000 residents who inhaled the vaporized sludge.

In other words, it’s the perfect setting.

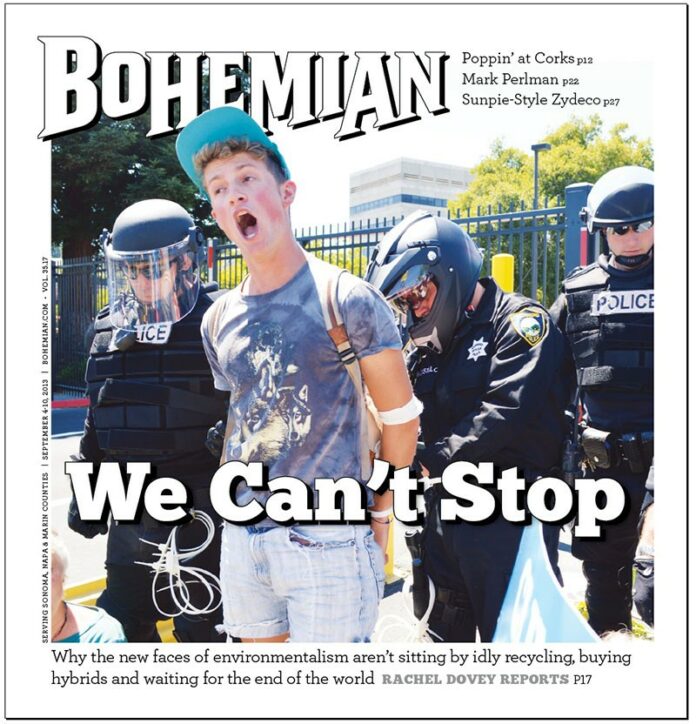

As fog dissolves into concrete heat on an August morning, 2,000 protesters march down West MacDonald toward the refinery’s gates. They carry signs echoing other social movements—”Occupy Chevron”—and sing “America the Beautiful” and “We Will Overcome.” From white-haired hippies holding sunflowers to Ohlone tribe members carrying a giant banner reading “Pissed” to college kids in camo with painted cardboard messages of “Separate Oil and State,” there’s a distinctly moral tenor to the rally. It will end almost too poetically with a massive sit-in in the refinery driveway—where a Chevron flag waves beside the one with stars and stripes—and 210 arrests.

Along with protests in Ohio, Washington, D.C., and Utah, this rally’s stark, urgent narrative of good vs. evil is intentional. Cosponsored by environmental nonprofit 350.org, it’s part of a national effort to shift the climate-change debate from partisan gridlock at the congressional top and do-what-you-can green consumption at the individual bottom. According to founder Bill McKibben—contributor to Rolling Stone and the New Yorker and author of The End of Nature—it’s time to organize, Civil Rights–style. And it’s time to vilify oil conglomerates like Chevron as though they were tobacco companies or Apartheid-era South Africa, divesting from pensions that fund them, getting arrested on their properties and giving the fight against climate change what it so desperately needs: an enemy.

McKibben’s approach may sound simplistic, especially to an environmental mainstream that has, for years, preached something equally true: Chevron was not created in a vacuum. After all, the company’s tea-colored, shimmering liquid is filling our SUVs—aren’t we the problem, not them? But McKibben argues that the personal responsibility mantras of hybrid buying and biking, while important, just aren’t enough. They aren’t enough to combat wildfires and hurricanes, ocean rise or carbon flooding the air. They aren’t enough to mandate cap-and-trade laws or encourage solar on a massive scale, even though the technology exists. And they’re no match for the billions of dollars poured into studies and campaign contributions assuring 46 percent of the country that everything is A-OK.

And so, perhaps fueled by simple desperation, McKibben’s moral movement is gaining some unlikely support.

A gangly, white-haired college professor from Vermont, McKibben comes off like a doomsday prophet—albeit a humorous one that can back up his claims.

“I’ve now, quite unexpectedly for me, been arrested a few times, and it’s not the most fun thing in the world, but it’s not the end of the world, either,” he says to the thousands gathered at the march, right before he walks into Chevron’s driveway and is cuffed and led to an armored car.

“The end of the world,” he says, “is the end of the world.”

[page]

In a political sphere where climate change, if accepted, is usually viewed as a problem that we should prepare for somewhere in the distant, murky future, his words might sound sensationalist at best, run-for-the-hills at worst. But read his detailed, three-decade coverage of continental ice melt and hurricanes like giant whirlpools spinning the warming seas, and his words start to sound sane—especially coupled with his equally detailed, three-decade coverage on why nothing’s being done.

One of McKibben’s most widely read pieces—”Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math”— appeared last summer in Rolling Stone. It outlined several things. The Copenhagen Accord, an agreement signed by world leaders in 2009, set a cap of 2 degrees Celsius average global temperature rise. When the article ran, scientists estimated that industrialization had already caused an average bump of 0.8 degrees, which had by then caused one-third of the Arctic’s summer ice to disappear and made the world’s oceans 30 percent more acidic. That marker was contested by two leading climatologists, James Hansen of NASA and Kerry Emanuel of MIT, who predicted that 2 degrees could churn up wetter, stronger, deadlier hurricanes and obliterate low-lying island nations and most of Africa. But it stuck.

And so a “carbon budget”—the amount of CO2 that can still be allowed into the atmosphere before we reach 2 degrees—was set at 565 gigatons, which the global economy will reach in about 15 years, according to many analyses. And the amount of oil and gas reserves that energy companies and countries like Venezuela and Kuwait (which “act like fossil-fuel companies,” McKibben writes) already have right now—that amount would release five times the carbon budget. According to McKibben, those reserves are “figured into share prices, companies are borrowing money against [them], nations are basing their budgets on the presumed returns from their patrimony.”

In other words, he says, they want to burn it all.

The scariest thing about McKibben’s armageddon is that it’s real. He may be shouting fire, but he’s no outlier. While the exact course that temperature rise will take is difficult to predict, a staggering 95 percent of the scientific community believes that unless we do something soon, we’ll roast. More tidal waves will crunch coastal homes. More Yosemite camp-outs will be replaced with photos of sequoias charred in a pink, dreamlike haze.

And as McKibben wrote over 20 years ago in The End of Nature, rising temperatures could be escalated by “feedback loops.” If the arctic disappears, there will be less white stuff reflecting light and heat back into space. And if the arctic tundra goes, there will be a whole lot less springy, moss-colored vegetation soaking up CO2. And so one thing—like that infamous butterfly wing—can set off a chain reaction in which this whole beautiful, devastated orb dissolves in wind and flames.

But McKibben didn’t run for the hills; he took to the streets. In an email interview—he was zipping from rally to rally at the time—I asked when he finally switched from impartial journalist to activist.

“Right about the time the Arctic melted in 2007,” he replied. “It [was] pretty clear physics was forcing the pace of the discussion.”

He added that 350.org was also created with “the desire to go on offense against the fossil fuel industry, not just playing defense against bad projects. We need people to understand that they are today’s tobacco industry, a set of thoroughly bad actors that we must take on if we’re ever going to get rational policy out of D.C.”

But when the fate of cap-and-trade legislation is to litter the Senate floor, when Chevron donates millions to keep republicans in the House and when nearly half of the country is still unconvinced by climatologists near-unanimous statement that, yes, this is man-made—what can 350 do?

The only thing they can, say members. Expose the Chevrons of the world, and hope that someone takes notice. And do it everywhere, not just in D.C.

‘We’re with our supporters, standing on the side of the political system looking in,” says Jay Carmona, a divestment campaigner with 350.org. “We’re working with the folks who are saying ‘It’s a pretty rigged game.'”

The nonprofit aims to be a traditional grassroots organization, empowering individuals instead of political reps. Along with marches like the one in Richmond, it tries to do this through an ambitious website, which is a basically a one-stop-shop for activists in training. Visitors can read the works of NASA climatologists and learn the ins and outs of divesting their schools, churches and city governments from pension funds or endowments in companies like Chevron or Shell. They can start petitions and sign up for “de-escalation” trainings, where they’ll learn how to politely risk arrest. And they can educate themselves about everything from the Keystone Pipeline to fracking in Delaware to India’s battle with coal.

Sonoma County’s chapter mirrors national’s loose structure.

[page]

“Many of the other organizations around here have a more specific focus,” Gary Pace, one of the cofounders of local 350 says, mentioning the Post Carbon Institute and Climate Protection Campaign. “We’re trying to be a place for someone who reads the paper and gets concerned, and can go to a demonstration or work on divesting or get involved with any of those more specific projects.”

The organization’s decentralization, online base and distrust of business-as-usual politics beg a comparison to Occupy. In Richmond, the earlier movement is palpable. A training for those risking arrest takes place before the march at the Bobby Bowens Progressive Center, where posters read “Criminals Wear Suits.” Later, while McKibben is speaking, a 350 volunteer walks around with a clipboard and “99 percent” T-shirt. It’s pretty clear that many of the players, at least on the local level, are the same.

But though Occupy is often caricatured as drifting aimlessly in leaderless decentralization, McKibben believes that parts of its structure (or lack thereof) could actually work for a climate movement. After all, global warming is just so . . . global. It’s difficult to see how all the pieces fit together, difficult to care. As Joey Smith, a teacher at the Santa Rosa Junior College beginning a 350 divestment campaign says, the dry concepts of climate change can seem impersonal.

“The numbers have been so incremental, it would be like getting people to be upset about trash in space,” he says, adding that unless you understand how climate change is directly harming people, it can seem as intangible as the weather. “I’m positive 350’s been trying to put a human face on the issue.”

Or many regional faces. As McKibben says in Richmond, places where Chevron has been a bad neighbor are everywhere. Global warming may be impersonal, but that black vapor which rose like a mushroom cloud over the bay last year—that’s not. That makes people angry enough to organize, angry enough to march into a driveway and risk arrest.

A line of police in riot gear greets the crowd that walks onto the cement slab bordered by an iron fence. Immediately, they begin pulling sitters to their feet, cuffing them and leading them away. One says that she’s a nurse.

“I treated people from the fire last year,” she shouts, as she’s pulled up.

Unlikely activists abound, and for many, this is their first arrest. There’s Melody Leppard, a 21-year-old with red hair and a knit hat who admits to being nervous but tells me “petitions and protests just aren’t enough.” There’s Nancy Binzen from Marin, a 64-year-old who’s also never been arrested. There’s Pace—of Sonoma County’s 350—who’s here with his kids. While waiting at the end of the driveway to go forward toward the police, he says he’s here because getting arrested is something he can actually do. “I’m a family doctor in Sebastopol,” he says. “I’m part of the system.” There’s a short, white-haired woman who comes forward and announces that she’s “90-and-a-half,” to be cuffed along with her grandson. Her shirt reads: “We are greater than fossil fuels.”

Not everyone is impressed with the waving sunflowers and chants of “Let the people go, arrest the CEOs.” A photographer covering the arrests—which take hours; there are over 200 people sitting in the driveway—tells me he thinks it’s a waste of time.

“This does nothing to convince the people who aren’t already convinced about climate change,” he says, alluding to that 46 percent. “This only makes people feel good.”

It’s a fair point. While 350 has so far successfully helped four colleges divest from fossil fuel companies and held rallies all over the country—one in Washington, D.C., attracted 50,000 people—its end goal has to be sweeping political overhaul if it’s serious about keeping oil in the ground. And that has to come in part from an energized voting population, not one that’s deeply split. I overhear one police officer muttering to another, about the crowd: “OK, you’ve made your point.” Another adds, “There could be a triple homicide today, and where would we be?”

But with 90-year-olds and 21-year-olds getting arrested, with white people from Marin and Latino labor unions from the East Bay and women and children in hijab, this feels less like some kind of privileged agenda—as environmental causes are so often portrayed, alienating many—and more like a community coming together. It’s a year after the fire. The city is suing Chevron. Even the police chief will later tell reporters, “We don’t work for Chevron. We work for the community.”

It feels like there’s a collective enemy. And it feels like a start.