The most insightful part of Douglas Gayeton’s new book, Local: The New Face of Food and Farming in America (Harper; $34.95), might be the afterword, where he discusses the unfortunate fate of the term “climate change”: “What we can’t comprehend, we avoid. We tune out. Call it climate fatigue.”

That sort of fatigue encompasses many hot-button issues, including our food supply, the production of which is inextricably linked with climate change. It takes time, energy and discipline to stay on top of this stuff, especially when the rhetoric is all about fear.

And I’m tired of people telling me to be afraid of food. Even when fear is grounded, there’s only so much we can get out of it. It inflames our passions quickly, but exhausts them just as fast. Enter Local, part of a multi-platform project called the Lexicon of Sustainability.

The project is about hope, locality, and ordinary people taking action on large and small scales. The idea is that words come before actions. As Gayeton writes, “words illuminate.” Creating a shared language of terms—”a real food dictionary”—educates consumers so they know what they’re eating and who ultimately benefits from the money they spend.

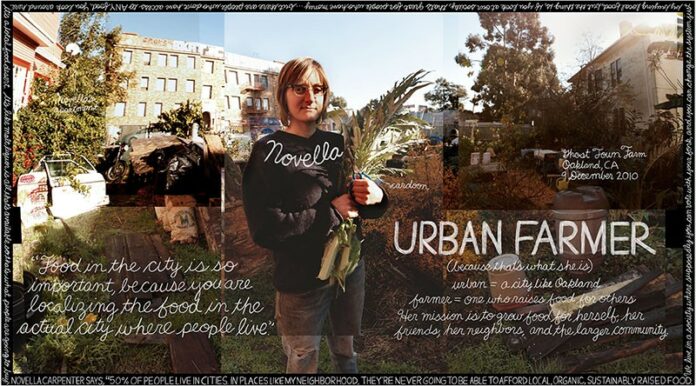

Gayeton, a Petaluma resident and multimedia artist, cofounded the Lexicon with his wife, Laura-Howard Gayeton (North Bay residents may have some familiarity with Laloo’s, her goat’s milk ice cream company). He traveled across America, interviewing and photographing farmers, scientists and entrepreneurs in both urban and rural environments to learn more about how they generate abundance using sustainability. The result, documented in Local, is a growing bank of over 200 terms, each illustrated with a colorful photo collage overlaid with Gayeton’s folksy handwriting.

These “information artworks” are dense with color and words, as saturated as a modern-day Book of Kells, but the general idea comes across pretty quickly. For instance, “cage-free” only means the poultry was not raised in a cage; it says nothing about how it was raised (most likely crowded and indoors, as it turns out).

You can also see the information artwork on the Lexicon of Sustainability website, and watch the series of short “Know Your Food” videos. The book is advantageous because it’s a bit stickier; you can read it in bed, peruse over it at breakfast and leave it out for friends to flip through. It’s interesting to see how different bits and pieces shine in each medium, even though they essentially use the same content.

The Lexicon collects the terminology of both boutique food producers (“heritage breed”) and social justice (“food security”), allowing them to coexist on the pages of Local without the antagonistic attitudes that flourish around the difference between the haves and have-nots.

This is something I struggle with, especially with the food-rescue nonprofit I work with in my own community. Is it better to focus the organization’s resources on delivering our clients the finite fresh produce grown in our community gardens, or recovering massive amounts of sugary day-old pastries? The pastries feed more people, but the homegrown tomatoes and sweet corn generate more positive comments than anything else we deliver. There’s value in both actions.

This kind of small-scale, daily activism isn’t for a cultural elite. It’s not just for people who have time to garden or know the difference between a turnip and a daikon. And it’s not just for rich, middle-aged white people. (It’s nice to see different shades of brown skin, as well as teenagers and seniors, in the book.)

Gayeton’s emphasis isn’t on what we’re against, but what we’re all for. Pleasure, not guilt, is the point. There are no ominous synthesizer chords scowling in the background of the “Know Your Food” films. In Local, Gayeton playfully refers to what I assume is Monsanto and their agribusiness cohort as “the companies that must not be named.” It’s not only OK to receive pleasure from cultivating food on small urban plots or spending what may seem to be an unreasonable amount on sustainably caught wild fish, it’s essential. As the saying goes, you attract more bees with honey than you do with vinegar—even if it’s unfiltered vinegar made from the cider of pesticide-free Gravenstein apples. If you’ve been paying attention to the news, you know we all need more bees.

We can end with the beginning of Local: “After reading this book, please give it away. You’ll know who it’s for,” writes Gayeton in the introduction. I want to give it to my crunchy hippy friends, and my arty design friends. But also my friends who sneer at the farmers market but are happy to spend $12 on breakfast at Denny’s. Or people just like me, who buy those damnable pizzas at Trader Joe’s even though they come in frozen all the way from Italy. As it turns out, we can all use illumination. Even people who are already enlightened.