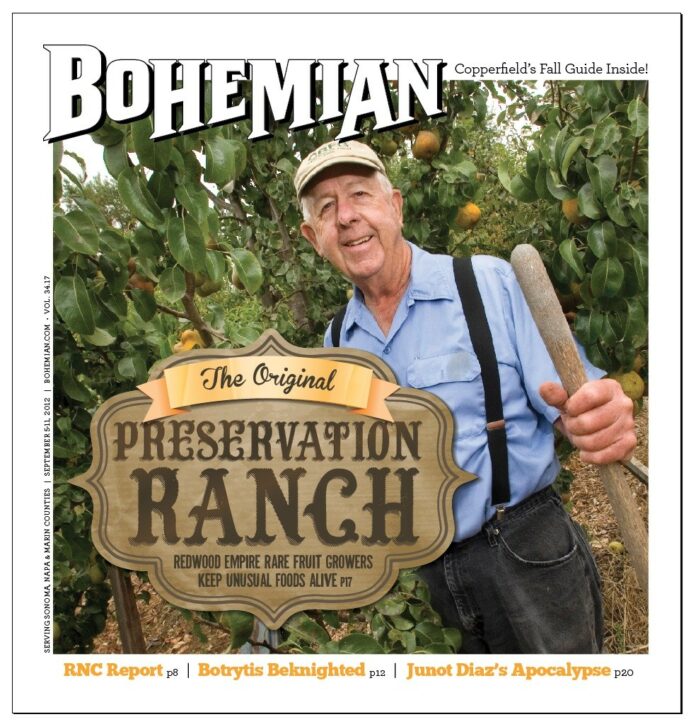

“This is an amazing world when you get into plants,” says Phil Pieri, approaching a Japanese raisin tree. “This tree produces a flower, kind of a long-stemmed thing. When you pick the flower and eat it, it tastes just like raisins.”

A member of the California Rare Fruit Growers of the Redwood Empire, Pieri has Illinois peaches and Pakistani mulberry, Japanese plums, Argentinean ombu, Washington navel oranges and 10 kinds of dragonfruit from who-knows-where. He’s also got Mexican grande avocados planted from seeds from Luther Burbank’s farm in Sebastopol. But his favorite fruits are native to California. “Peaches,” he says when asked. “I love peaches, and a good pluot.” Between bites of the latter picked from his tree, with juice dripping down his chin, he exclaims, “Oh, delicious!”

It may seem odd to scour the globe for fruit that may or may not thrive in the local Mediterranean climate. But Pieri and his fellow rare fruiters consider cultivating, grafting and trading rare fruit trees a tribute to the fertile land, affable climate and agricultural heritage of the North Bay. He has over 300 different varieties of fruit on his one-acre plot in rural Sebastopol, some kept in a greenhouse to escape the coolness that can harm the more tropical varieties, like che or white sapote.

The growers are varied in focus. Some, like Pieri, specialize in exotic fruits. Others are passionate about preserving heirloom species like the Fort Ross Gravenstein, the original apple brought to Fort Ross when Russian settlers arrived about 150 years ago. “We’re trying to perpetuate the variety,” explains Pieri. “It’s a Gravenstein, basically. I hope it’s good, I haven’t tasted it. This is the first year it’s had anything on it.”

Contrary to Burbank’s mission of innovation, Pieri says the Rare Fruit Growers focus on preserving what’s already known. “I don’t develop new varieties; I take the old varieties, things that don’t normally grow around here, you don’t see in the store,” Pieri says. “That’s what our group is all about. We’re kind of like Johnny Appleseed, you might say. We want to perpetuate and protect the rare varieties that aren’t sold commercially and that you don’t see very often from disappearing. And a lot of them have already.”

The beloved Gravenstein might be next. According to the Rare Fruit Growers, Sonoma County’s Gravenstein orchards have declined by almost 7,000 acres in the past 60 years, down to about 960 acres. “There are probably, worldwide, about 10,000 varieties of apples,” says Pieri. “About three or four thousand of those have already disappeared—that are recorded already. You can’t find them anymore, they’re not there.”

[page]

Banana Love

Another plant that does surprisingly well in the affable North Bay climate is the banana. Vince Scholten, also known as Vince the Bananaman, has about 40 varieties in his greenhouses at NorCal Growers in Sebastopol—and all because he initially thought it’d be cool to have a banana plant in his huge, one-acre greenhouse.

“I was a cut-flower grower at the time, and realized quite quickly that cut-flower growing is wonderful but it’s very time-consuming,” says Scholten. “My other love was just growing plants and propagating things. And so we opened up the nursery and started selling plants.” Bananas quickly became his niche.

Scholten sold only the plants, because selling the fruit was difficult; all the fruit on a given plant ripens at the same time, and to sell that many bananas for just a short period of time each year would not have been feasible. There was money in the banana stand until 2010, when the economy started to go rotten. He had 70 varieties—4,500 plants in all—in one greenhouse at the business’ peak, but then Scholten injured his back, and, he says, “I couldn’t keep up with the gophers.” (Banana plants, which are the world’s largest herb—the fruit is also an herb—are soft and full of water, which burrowing animals love.)

Scholten’s biggest seller was a banana called “ice cream.” Its blue fruit, as it turns out, tastes just like vanilla-banana ice cream. Though not commercially available, it’s relatively simple to just grow in this area, even without a greenhouse. “There are pockets around every person’s house that you can plant a banana,” says Scholten, “and because it’s hot, you can get fruit.”

Though the banana business is busted for now, Scholten still utilizes his three enormous greenhouses to grow food crops like tomatoes, herbs and lettuce. He also specializes in trellised trees, taking years to train them to grow along a fence, allowing for greater fruit production in a smaller space. Scholten has over 250 varieties of fruit on his property, and not all are grown for commercial reasons. His Indian blood peach, for example, growing on the side of the dirt road leading to a greenhouse, “makes the best jam you’ve ever tasted.”

[page]

Graft Jam

Everyone enjoys fruit, but not everyone has acres of land to plant it. How can one grow multiple varieties of fruit trees on an apartment balcony? Simply stick a branch from one tree into the branch of another and let nature do the rest.

Rare-fruiter Keith Borglum describes grafting this way: “If we cut your finger off and graft it onto him, it’s your meat, so it’s gonna grow and look and be like you.”

The graftee in the example chuckles, adding, “Unless I reject you and it falls off.”

The possibilities of grafting are restricted only to the amount of fruit in one family. One rare-fruit member reportedly has taken this to the extreme, with a hundred varieties on one tree (he calls it a “fruit salad tree”). But it’s not uncommon to have around 10 different varieties on one strong rootstock. It saves space, and provides the ability to trade and try new varieties with minimal effort.

Passion for the Unusual

Pieri has such a wide variety of pears fruiting at different times of the year that he can pick tree-ripened fruit in his backyard in almost any season. His sour cherry tree produces fruit so red it looks radioactive. And there’s sorbus, a small, persimmon-like fruit that ferments in its own skin. “You wait until it falls to the ground and turns brown and all mushy and ugly as sin, and you taste it; I like it,” says Pieri, implying that he’s in the minority. “That’s when it’s fermented and you can actually taste the alcohol.” Not quite enough to bother trying to get drunk, he says, “but enough to tell it’s there.”

Though he has a plenty of peculiar fruit, Pieri is known to some as “the babaco guy.” Babaco is a papaya relative with melony flesh and a unique, semi-sweet and slightly acidic flavor. He’s tried to introduce babaco to area markets like the Berkeley Bowl and to chefs, including John Ash, but to no avail. “People are not used to it; they didn’t care for it, it just didn’t go over,” he says of the Ecuadorian delight. “I was trying to find out if it would be commercial, and I don’t think so, here.”

That’s not his main focus, though. “I don’t try and sell them,” says Pieri. “I don’t have the time or the inclination. I just grow them, and most of them just go over the fence to the cows.”

So why even bother? For Pieri, the process is as important as the end result. “It’s kind of a passion with me,” he says. “I just like to grow things.”

The Rare Fruit Grower’s annual Festival of Fruit, this year combined with the National Heirloom Expo, takes place Tuesday-Thursday, Sept. 11–13, at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds. $10 daily; $25 three-day pass. The rare fruit growers host tours and a welcoming reception on Sept. 10. See www.festivaloffruit.org and www.theheirloomexpo.com.