Duck & Cover

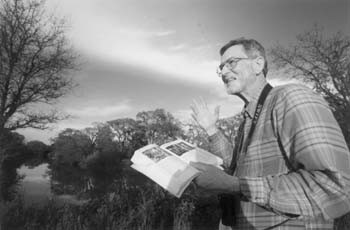

Nature’s way: Docent chief Bob Evans identifies wildlife living in the newly restored Laguna de Santa Rosa–one of the county’s conservation success stories.

Sebastopol’s Laguna de Santa Rosa goes from wasteland to wetland

By Janet Wells

DON’T TAKE a picture of that bird!” yells Bob Evans, waving his arms at a photographer getting ready to capture the serene twilit scene of a duck skimming along a pond in Sebastopol’s Laguna de Santa Rosa. “It’s a farm duck. It’s not native,” says an indignant gray-bearded Evans.

Evans, carrying a well-worn Field Guide to Birds that seems to be an extension of his hand, is understandably territorial about the laguna. Head of the new preserve’s docent program, Evans sees a place transformed by community donations and countless volunteer hours from a trash heap to a thriving riparian wetland that plays a crucial part in the area’s ecology and cultural history.

Bragging like a proud father, Evans says that the pond–covered in a startlingly bright green scum called duckweed–is one of the best refuges in the country for migratory diving ducks.

“It’s right on the [Pacific] flyway,” says Evans, eager to showcase the laguna’s potential as magnet for native flora and fauna. “You want a list? Ring-neck, ruddy, grebes, common loon, scaup–that’s s-c-a-u-p–redhead, American widgeon.”

Evans interrupts himself to grab his binoculars and peer at a flock flapping overhead. “The nice thing about taking people into the laguna for the first time,” he says, “is their eyes get wide with the beauty.”

Most people, Evans, adds, have seen the laguna only as they drive along Highway 12 into Sebastopol, through grassy fields that flood every winter. But those fields are only a small part of a waterway 14 miles long stretching from River Road to Cotati, the largest tributary of the Russian River.

Depending on the time of year, the laguna is wetlands, stream, or floodplain, providing habitat for nearly 300 species of plants and more than 250 kinds of birds. For years the city of Sebastopol used the land for sewage treatment ponds and as a dumping ground. Then, 20 years ago, the laguna was recognized as a resource worth restoring when Sebastopol’s general plan identified the 75-acre city-owned site as a potential park and efforts started to protect it from development.

The Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation received a jump start from retired builder Emmett Blincoe, who donated $200,000 to make improvements to the park, including the just completed mile-long trail in memory of his late wife Loretta, and the planting of more than 1,500 trees and shrubs, and debris cleanup.

This week, Blincoe announced that he is giving an additional $200,000 for further restoration and improvements, including a bridge and a path along the east side of the laguna. The 71-year-old nature enthusiast is intensely private, bestowing his gifts through his attorney.

“Most of us have never met him. We talk to him only through his lawyer,” says Jeffrey Edelheit, a board member of the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation. “His wife loved it here. We gave him a tour and he said, ‘This is it.’ ”

BLINCOE ISN’T the only laguna fan. More than a few people, it seems, are downright zealous about the place. “When you come out here, you’ll feel the essence of the laguna,” Edelheit says. “You have to feel her. All of the wildlife is nurtured by her.”

Even stoic scientists start to wax poetic when it comes to the laguna. “There’s an expansiveness to it, and I don’t want to get soppy about it, but there’s a sense of peace,” says hydrogeologist Kim Cordell, director of the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation. “The appeal is the same as the ocean. There’s a consistency, but every time you go it’s different.”

This time of year the laguna looks like a waterway in the Deep South–a swampy, slow-moving river, trees and shrubs hanging over the banks and trailing in the brow-green water.

Himalayan blackberries, growing eight feet tall along the banks, have been ripped out, replaced by native trees and bushes. Volunteers salvaged native bunch grasses from the Walmart construction site in Windsor, replanting more than 500 little clumps of green grass along the laguna path. Benches line the path, offering sweeping views of willows and valley oaks reflected in the water, Mt. St. Helena visible in the distance across fields bright with yellow mustard.

The laguna is central to the area’s Native American history, its abundant natural resources sustaining settlements for more than 8,000 years. “That laguna is so important: it supported a village that went from Palm Drive Hospital to the apple cannery. That was a large community of people,” says Foley Benson, coordinator of Native American studies at Santa Rosa Junior College. “It was a major trade route to the coast.”

The park’s first group of docents is going through an extensive training program, with the goal of providing classroom education and trail experience for elementary school classes in the region. In addition to spotting green egrets and bunch grass, kids who have Evans as a tour guide will be sure to pick up some tips on wastewater and its role in the laguna’s restoration. First lesson: Don’t call it sewage.

“It’s tertiary treated,” Evans barks. “It’s clean. It would be potable in 99 percent of the countries of the world.”

The water quality of the laguna has improved enough in the past 10 years that the bird population count and number of species are dramatically up, Evans says. But the restoration efforts are far from complete.

“We’re all looking for the yellow-billed cuckoo,” he says, opening up his Field Guide. “It’s a riparian bird and lives in waterways with thick growth. When we have our first yellow-billed cuckoo back, that will mean we were successful. We’ll have a huge party.”

The Loretta Blincoe Trail will be dedicated at the second annual Laguna de Santa Rosa day, Sunday, May 2, starting at 9 a.m. For more information, call 823-9428.

From the April 22-28, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.