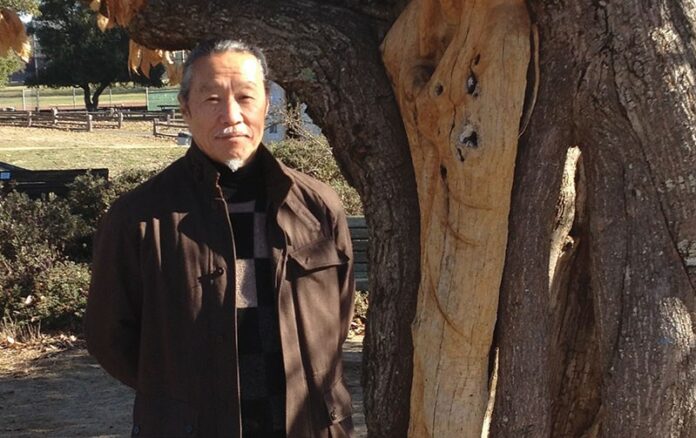

‘This is my dream,” Kitaro says simply.

He’s speaking of the transformation of some of his most famous electronica melodies into fully orchestrated tone poems. It’s not a new idea, just one that has taken a long time to realize for the Japanese composer, whose elegantly melodic instrumentals helped define the emerging “New Age” genre beginning in the late 1970s. Although he was encouraged to explore the tonal potential of early synthesizers by Tangerine Dream’s Klaus Schulze, and did so with great success, he longed for more.

“The synthesizer can create strange sounds, but [an] orchestra has its own beauty,” he says. “[From] the beginning of my career, always I’m focused on the actual acoustic sounds.”

When director Oliver Stone tapped Kitaro to write the score for his 1993 film Heaven and Earth, a large studio orchestra recorded the soundtrack. It was, the composer says, “soooo good. So, little by little, the last 20 years, my music is moving toward the real orchestra.”

And now, he adds, “the opportunity of working with the Santa Rosa Symphony, this is my dream.”

For the orchestra, however, it was a surprise.

“It just dropped in our lap,” says Alan Silow, the Santa Rosa Symphony‘s executive director. An out-of-the-blue call from Sonoma State University music professor Brian Wilson in November introduced the possibility, and when Kitaro’s desired Feb. 14 date turned out to be narrowly available (subscription concerts had long been scheduled for the rest of the weekend), planning accelerated, and the unusual joint performance was announced just a few weeks later.

“They didn’t hire us as ‘the band,'” Silow states, “We’re partners in the whole production.”

This concert will include music from Kitaro’s best-known recordings, such as Silk Road, Thinking of You and Kojiki. After this week’s premiere with a scaled-down version of the Santa Rosa Symphony—roughly 40 strong—the program continues with half a dozen other performances, and with other orchestras, in Russia, Eastern Europe and possibly some later dates in Southeast Asia. The show could also tour the United States late this year.

Other projects also await Kitaro: a new collaboration with percussionist Mickey Hart and the completion of his ambitious Ku-Kai Project, a series of 88 compositions that incorporate the sounds of the temple bells from the 88 temples that ring Japan’s Shikoku island. He’s written and recorded 39 so far, and expects the remainder to occupy him for four to five years.

But now his priority is to

finalize the set list, complete the orchestrations (with his long-time band leader Stephen Small, who will also conduct) and prepare for the single three-and-a-half-hour rehearsal with the symphony musicians. But even with strings, brass, woodwinds and percussion—and, of course, Kitaro’s own six-piece electronic band—there’s still one element missing.

“I think, still, the voice is the best sounding instrument,” he explains, “so I will do some surprise for the audience this time.

“One song I will sing myself.”