By Sara Bir

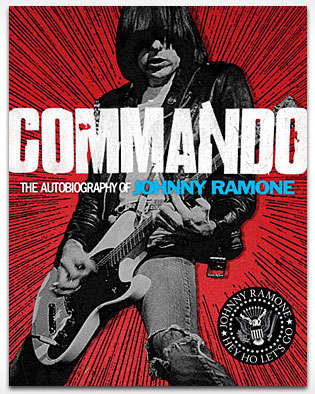

Johnny Ramone’s posthumous autobigraphy Commando: The Autobiography of Johnny Ramone fired up the second wind of Ramones fandom I’ve been yearning for. The book came out in April, but in a frugal move that I think Johnny would have approved of, I put a copy on hold at the library and waited it out.

Have you ever loved a band so much that you reached a bodily saturation point, whereupon listening to their songs felt unnecessary? There was so much Ramones flowing through my bloodstream I couldn’t absorb any more. I didn’t put my Ramones albums away, though for quite a few years I seldom played them. But simply thinking of myself as a Ramones fan (albeit one in hibernation) brought me soothing relief during low periods. If nothing else, I believed in all things Ramonesey, something that goes beyond a shelf of records and a gazillion performances and four guys (seven, actually) wearing leather jackets. I knew my auditory need for the Ramones would return someday, along with a renewed sense of pleasure, and it was Johnny’s book that did it.

Johnny is not my favorite Ramone. In a band of guys who are hard to love, Johnny is the hardest to love. He was the every-scowling tyrant, practical to the point of being unfeeling. The man we see in Johnny’s interview segments of End of the Century: Story of the Ramones appears to carry little sentimentality for his Ramones years, nor compassion for the difficulties of his former bandmates. I was anxious to read Commando, for fear it would only reinforce this image.

The color scheme of the book is red, white, and blue, natch; Johnny drove American cars and followed baseball, a hearty American sport, and when he drank, he drank American beer. Flip through Commando casually and you will spot multiple photographs of Johnny Ramone smiling. You will also see a picture of Johnny having a blast on Walt Disney World’s dinosaur ride in the company for friends and his wife, Linda. Don’t worry, you’ll spot plenty of sulky photos, too. What we also get is a more complete impression of Johnny as a person, as a feeling human with a sense of humor, though it’s hard to tell where the stage frown of the image (and Johnny was keenly aware of the importance of the band’s image) stopped and the actual frown began. Johnny’s genius was to harness the dynamism of his inherent anger—he readily admits he was a teenage hoodlum for no good reason, the archetypical rebel without a cause —and channel it into a focused musical ferocity, a process through which a negative force refracted into positivity energy. Joey’s distinctive vocals and Dee Dee’s lyrics about mental instability were just the icing on the cake; it was Johnny’s flurry of buzzing guitar that formed the backbone of the Ramones’ sound and their spiritual essence.

Commando (edited with care and competency by John Cafiero, manager of both Johnny and Dee Dee’s estates) is thrillingly brief and direct; Johnny’s voice rings true and sharp. He still comes off as a jerk, but that’s part of the point. Johnny despised phonies; not one to deny his own true nature, he’d probably consider a faker to be the biggest jerk of all.

A few months ago, Rock and Roll High School played at a second-run theater where I live. I asked a new friend of mine if she’d like to go, because Rock ‘n’ Roll High School is way more fun when you’re not alone. I wore a Ramones t-shirt, thinking “Jesus, I am such a dork”—but it was impossible to not wear it.

When I met my friend in the line to buy beer, I saw she had a Ramones shirt on, too. So did about half of the people who showed up. I was proud of us, old fogies all. You haven’t truly seen Rock ‘n’ Roll High School until you’ve seen it from the balcony of an old movie palace with the better part of a pitcher of beer in your belly, too far gone down the road of life’s disappointments to care if wearing your decades-old Ramones shirt to a Ramones movie is cool or not. The scene came where Johnny pokes Miss Togar in the butt with his guitar and says, with typical flatness, “We’re not students, we’re the Ramones.” Everyone laughed.

I found my dubbed cassette tape of Ramones Mania in our shed. It’s one of the few Ramones tapes I’ve owned that didn’t eventually warp in the summertime heat of my old car or get its innards irreparably shredded in a gunky cassette player. It’s summer now, and I’ve always thought the Ramones sound best in the summertime. Feeling carefree, I played it while driving my daughter home from daycare, a time I usually eschew music so was can chat about our day. Side Two came to an end, and for a moment only the hissing silence of the cassette’s dead space prevailed. “I like it better with the songs off,” she said from her car seat.

And that’s fine. She’s only two and a half years old, and hasn’t been seasoned by pain and frustration enough for that noise to resonate with her. So now I play that tape only when I’m in the car by myself, rejoicing in its curious arrangement of songs and how they sound different that way; Ramones Mania was how I became familiar with the band, and their actual albums long ago displaced this ersatz best-of collection. I don’t care if Frances never likes the Ramones; she’s my daughter, and as such, Ramonesiness is an inextricable part of her genetic makeup, which perhaps accounts for a fraction of why she’s so awesome.

Johnny Ramone, ‘Commando,’ and the Endurance of Ramonesiness

“I like it better with the songs off,”

kids don’t know good music these days…

Great book review! I myself have never ever been a Ramones fan, but I appreciate what they stood for and accomplished. I want to read Commando.

Gabba gabba we accept you, we accept you one of us!