Coming on the heels of Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, here’s our primer for movie-crazy, pop-cultural adventurers looking for seldom-visited territories to explore: Japan is ready for its closeup. Japanese cinema has a rich and rewarding history, but one that never seems to get the same attention eager American film buffs have always lavished on the Europeans. A trip to the real-life Land of the Rising Sun is out of reach while we’re in the throes of this pandemic, but thanks to streaming and other home-video options, we can cross the Pacific and immerse ourselves in, say, the intrigues of Tokugawa Shogunate, anytime we want.

Without delving into a comprehensive discussion of such a panoramic subject, here’s a bite-sized introduction to a few filmmakers and their movies, most of them available for streaming and all of them indispensable for anyone interested in this truly world-class national film industry. Names are listed Japanese-style, with family names first.

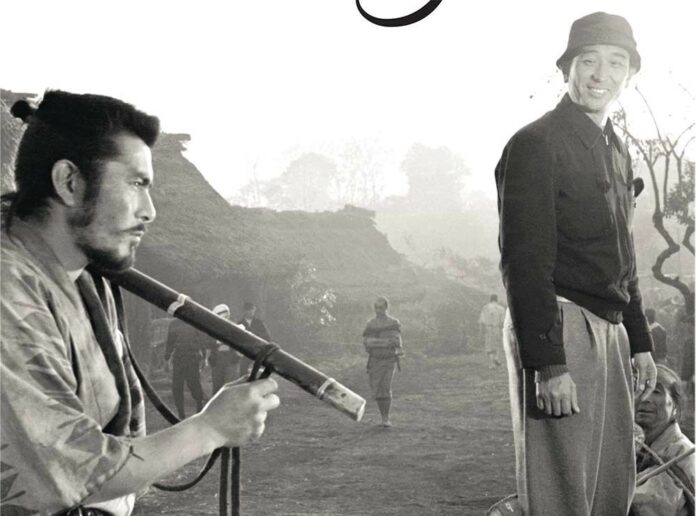

Kurosawa Akira: Arguably Japan’s most renowned filmmaker, Kurosawa reached for universal themes and found international audiences with: Seven Samurai (one of the greatest movies ever made); Ikiru; Rashomon; Throne of Blood (a feudal-era version of Macbeth, with three grotesque witches and the raging power lust in actor Mifune Toshirô’s eyes); The Hidden Fortress (a major influence on Star Wars); Sanjuro; Yojimbo; and the King Lear-in-feudal-Japan costumed epic, Ran. For a number of reasons, perhaps including his height—the filmmaker was almost six feet tall—Kurosawa stood out from his Japanese movie-biz contemporaries. Critics in his home country sometimes clucked disapprovingly about his choice of subjects—the Shakespeare adaptations, Seven Samurai’s tribute to Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes, etc., his popularity in the West and the “un-Japanese” point of view in many of his projects. He once described Seven Samurai as being as rich as a buttered steak topped with broiled eels. Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala—a 1975 Soviet-Japanese co-production with Mosfilm—is of special interest because its thrilling story of the friendship between a native trapper/guide and a visiting surveyor in the Siberian wilderness is presented in Russian.

Ozu Yasujirô: Considered by many to be the most quintessentially “Japanese” of the classical directors. His spare visual style and carefully constructed scenarios tell the stories of ordinary people dealing with the ordinary heartaches of life, with extraordinary grace. But don’t be fooled by Ozu’s reputation for “austerity.” His emotion-packed family dramas are a feast of characterization and repressed sensuality lurking just beneath the surface. For example: A Story of Floating Weeds; Tokyo Story; Late Spring; Early Summer; Tokyo Twilight; and Equinox Flower. Ozu is notorious for his habit of placing his camera, in indoor scenes, at the eye level of a person kneeling on a tatami mat. Hara Setsuko, one of Ozu’s most frequent leading ladies (her fond nickname was “The Eternal Virgin”), has one of the most radiant smiles in existence, even when portraying a compromised character.

Mizoguchi Kenji: A master stylist enthralled by the stories of women, whose low status in traditional Japanese society makes them vulnerable to injustice and mistreatment. Some of the saddest films you’ll ever see: Sansho the Bailiff, aka Sansho Dayu (the heartbreaking tale of an unfortunate family’s interrupted journey); Ugetsu Monogatari (a dreamlike ghost story from ancient Nippon); The Life of Oharu (a gorgeous weepie starring the lead actress of Sansho, Tanaka Kinuyo); Utamaro and His Five Women; Miss Oyu (also with the long-suffering Tanaka); A Geisha; and A Story from Chikamatsu (aka The Crucified Lovers). Mizoguchi’s compositions are as thrillingly composed as a ukiyo e masterpiece.

Writer-director Kurosawa Kiyoshi is no relation to Kurosawa Akira, but shares the older director’s affinity for depicting characters confronting moral and ethical dilemmas. His elegantly paced contemporary projects range from outright horror to eerie relationships to soulful character-studies of modern urbanites in distress: Cure; Serpent’s Path; Séance (an extra-creepy remake of Séance on a Wet Afternoon); the internet chiller Pulse; Doppelganger; and Tokyo Sonata, the 2008 story of a middle-class family’s downward spiral after the father loses his job.

Kore-Eda Hirokazu: “The New Ozu”? Kore-Eda’s closely observed dramas have a strong social consciousness, none more so than Nobody Knows, the 2004 story of a family of school-age Tokyo children abandoned by their mother. Also recommended: Shoplifters; After the Storm; Our Little Sister; Like Father, Like Son; Hana; Maborosi; and Air Doll, the tale of a lonely man who falls in love with his inflatable sex doll.

Suzuki Seijun: His jazzed-up, frantic, gaudy, sexy gangster-and-spy flicks of the 1950s–1990s made him a hipster art-house fav in the U.S. Dig these shiny entertainments: Branded to Kill; Youth of the Beast; Gate of Flesh; Tokyo Drifter; and the inimitably titled Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! Some of Suzuki’s most distinctive movies feature actor Shishido Jo, notorious for having tissue from his butt cheeks grafted onto his face, in an attempt to give him a more “Western” appearance.

Imamura Shôhei: Sardonic social and political commentary—with more than a touch of grim humor and sexuality—adorn this director’s hyperactive array of films from 1950–2000. The standouts: The Insect Woman; Pigs and Battleships; The Ballad of Narayama (Imamura’s adaptation of a story by Fukazawa Shichirô, first filmed in 1958 by director Kinoshita Keisuke); Black Rain (a moving protest against nuclear warfare); Vengeance Is Mine; The Pornographers; and Profound Desires of the Gods.

Honda Ishirô: Best known for creating the original Godzilla (Japanese title: Gojira, from 1954), Honda’s filmography is packed with loads of audience-pleasing sci-fi and horror spectacles, including: Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964, pick hit from the long-running kaiju giant-monster franchise); The Mysterians (1957); 1959’s The H-man (another atomic-age mishap); Destroy All Monsters (1968); and Matango (1963), the fantastic saga of a group of shipwrecked men and women battling a killer fungus on a spooky island—American tagline: Attack of the Killer Mushrooms.

Twisted genre excitement with a sadistic streak is the trademark of cult figure director Miike Takashi. One of his most unforgettable is Audition (1999), in which a selfish businessman tries to hoodwink a succession of prospective would-be “brides” and ends up paying the price. Also in Miike’s immense, bizarre filmography: irreverent cowboy actioner Sukiyaki Western Django; the enormously influential Dead or Alive; Ichi the killer; Blade of the Immortal (piles of corpses ad absurdam); and Over Your Dead Body.

For rip-roaring, costumed sword-fighting action, try: director Inagaki Hiroshi’s 1954-56 Samurai trilogy (Musashi Miyamoto; Duel at Ichijoji Temple; and Duel at Ganryu Island). Also fine: The Sword of Doom (1965) by director Okamoto Kihachi, with actor Nakadai Tatsuya’s amazing freakout bloodbath in the climactic scene. Further genre-action fun, from underworld intrigue to youth-market ultra-violence: anything by jack-of-all-trades Fukasaku Kinji, especially Yakuza Graveyard. Fukasaku’s Battle Royale movies, in which teenage contestants kill each other on a tropical island, outraged audiences and spun off a host of imitators.

Also recommended are the works of Oshima Nagisa (his intense sexual melodrama In the Realm of the Senses created a sensation in 1976); Naruse Mikio (the urban prostitute drama When A Woman Ascends the Stairs); and Shindo Kaneto (Onibaba, a ghost story about a predatory mother and daughter living in a marshland shack). Ichikawa Kon, director of acclaimed sports documentary Tokyo Olympiad, ranged over a variety of genres: family relationship dramas like The Makioka Sisters; the samurai adventure 47 Ronin (a remake of Mizoguchi’s 1941 samurai pic); and Ichikawa’s harrowing World War II nightmares, Fires on the Plain and The Burmese Harp. Kobayashi Masaki’s powerful three-part The Human Condition strikes a similar chord in tracing the ordeal of an anti-war Imperial Army soldier (played by Nakadai Tatsuya) stationed in Manchuria. Kobayashi’s trilogy clocks in at nearly 10 hours total running time.

Likewise on the bellicose side of the slate are the graphic tough-guy antics of actor-filmmaker “Beat Takeshi” Kitano (Boiling Point; Fireworks), and the comparatively benign swordplay of mega-popular actor Katsu Shintarō (“Kats-Shin”), who portrayed the blind masseur/gambler Zatoichi, defender of cute little kids and threatened women, in some 26 movies.

Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters (1985) is that rarity of rarities, an intelligent Japanese-language film by an American director, Paul Schrader. It’s a heavily stylized dramatization (starring actor Ogata Ken) of the life of controversial novelist-actor-militarist Mishima Yukio, who committed seppuku after unsuccessfully attempting a 1970 coup d’état in Tokyo. Before coming to his bloody end the real-life Mishima wrote and/or acted in a lengthy roster of art films and campy extravaganzas, including Black Lizard (1968) and Black Rose (1969), both of which starred “gender illusionist” Miwa Akihiro, and both of which were helmed by the above-mentioned Fukasaku Kinji.

Lastly, an easy choice from among the ocean of Japanese anime films is the oeuvre of the creative genius Miyazaki Hayao, guiding light of Studio Ghibli, who gave us the animated masterpieces My Neighbor Totoro; Princess Mononoke; Spirited Away; Howl’s Moving Castle; and Ponyo.

Many (but not all) of the above titles are available from various home video streaming services. Check JustWatch.com.