When wildfires swept across Santa Rosa in October 2017, local residents evacuated while reporters embedded themselves in the charred landscape. So it’s not surprising that early in his new book about the big blazes, Earik Beann encounters an Los Angeles Times journalist.

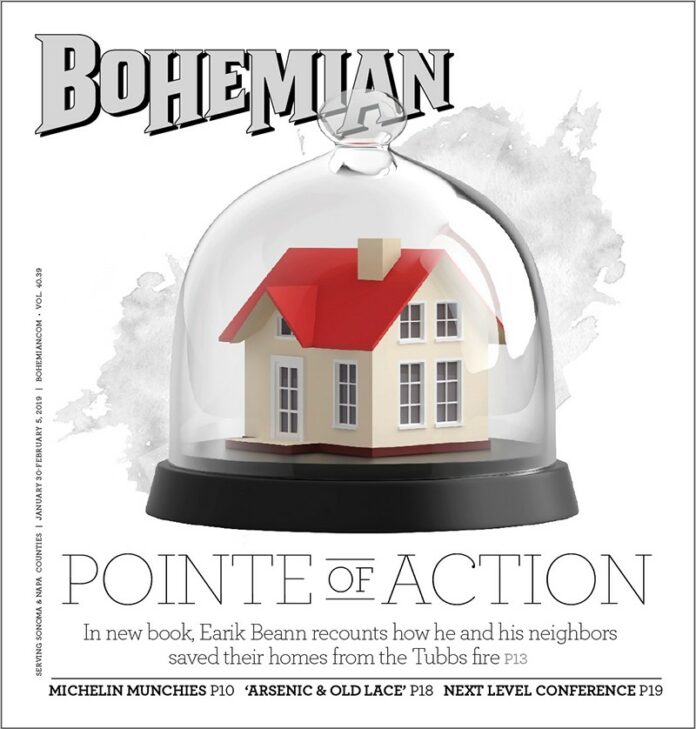

“It looked like we might get to be the story,” Beann writes. In fact, only a few reporters covered some of the doings of Beann and his pals as they extinguished fires, scared off looters and created a resilient community where none previously existed. The book’s title, Pointe Patrol (Profoundly 1; $16.95), comes from the street, Viewpointe Circle, where Beann and his wife lived a quiet life in Fountaingrove until the firestorms struck. They’re in their old home again, wiser about fires and firefighting.

“I wrote my book in secret because no one wanted to talk about what happened and I didn’t know if my neighbors would want me to tell our story,” Beann says. “They came around to the idea.”

He adds, “I was born and raised in Tennessee, but after my baptism of fire, I’m beginning to see myself as a Californian.”

Beann has never been a “hot shot,” as elite firefighters are known, but in Pointe Patrol, he comes across as a hot shot in his own right: an adept team player and savvy firefighter.

Rebecca Solnit, the Novato born and raised author, would point to Beann and his neighbors as the architects of the kind of social networks that arise from disasters. In books about Detroit and New Orleans, and in an article about Santa Rosa’s recovery from the fires for The New Yorker, Solnit describes the birth of mini paradises in hellholes.

Still, no reporter has told the dramatic story that Beann tells in Point Patrol, which is subtitled How Nine People (and a Dog) Saved Their Neighborhood from One of the Most Destructive Fires in California History. Beann is one of the nine people. His wife, Laura, is another. There’s also Gary, Wayne, Eddie, TJ, Mike, Sebastian and Dave, a retired fire chief. Their names have been changed to protect their privacy.

For the most part, Beann keeps the narrative close to the ground (the author eschews an overview of the catastrophic fire) and within his own Fountaingrove neighborhood, though near the end of his riveting narrative, he recounts the relevant stats: 250 individual wildfires, 245,000 acres burned, 44 people killed and 90,000 forced to evacuate. He pays homage to the firefighters and police officers heralded as first responders, and also shows ordinary folks playing heroic roles during the transformation of Fountaingrove from a quiet suburban neighborhood to a no man’s land and war zone.

We see the author and his team thinking and acting like firefighters and crime preventers, patrolling the streets every hour on the hour, night and day. Beann went out with his dog, Oscar, a hound who seemed to be able to sniff out looters and fires. If and when the team saw someone who looked suspicious, they approached, asked questions politely but firmly, and then either asked the person to leave or allowed them to stay if they had a legitimate reason to be there. A pickup truck with buckets full of water was always ready to go where and when they found a hot spot. Hoses were hooked up to outdoor faucets and extended all over the neighborhood. The whole place was covered.

Near the end of his account, Beann has an epiphany: “I realized that where you belong has nothing to do with the home you own. It has everything to do with the people around you,” he writes. “We weren’t fighting for our own properties. We were fighting for our community.” That perspective is rare in the sea of stories that have memorialized the things people lost and the properties that were destroyed.

Beanne has the courage to look critically at himself, and to describe how and why he changed his mind about things like guns and people like “vigilantes.” He’s also frank enough to describe what he and his wife called “end-of-the-world sex,” and to ask key questions about the connections between social crises and ethnicity. He wonders, for example, if the police would not have treated him with kid gloves if he were “a black guy.”

At the back of the book, there are eight black-and-white photos, including one of the author and his dog, Oscar, who was part of the team. Last weekend, at Copperfield’s in Santa Rosa, Beann sold and signed copies of his book and talked to friends, neighbors and one stranger who smiled and said, “I never met a real author before.”

Proceeds from the sale of the book go to families who lost a first responder. It’s a cause Beann happily embraces.