No matter the context—boom, internet or videogame hedgehog—when the word “sonic” comes up, people think of speed.

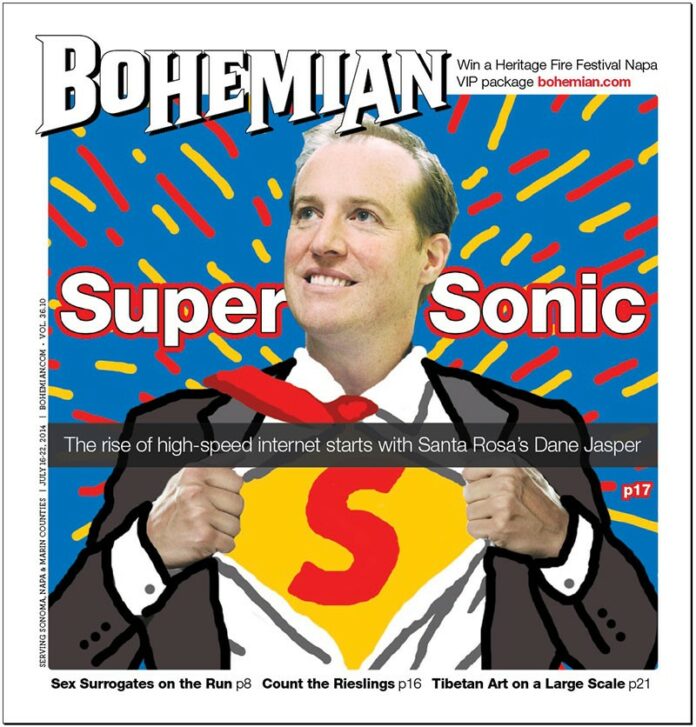

As for Sonic.net, the Santa Rosa–based internet provider, its growth hasn’t been as fast as others, but it’s picking up steam 20 years after its founding. Sonic is the first company to offer residential gigabit fiber internet service in California and is expanding into areas outside the North Bay. It survived the dotcom bust of 2001 and has made a name for itself as a champion of internet privacy. Not bad for a company founded by a guy who didn’t finish high school.

STARTED WITH A CRIME

It’s hard to find an internet company that’s been around as long as Sonic. Dane Jasper and Scott Doty started Sonoma Interconnect, which was later shortened to Sonic, as Santa Rosa Junior College student employees in 1994. The company celebrates its 20th birthday this month.

For perspective, how about a timeline: earlier in 1994 Yahoo! had just launched; AOL would come online the following year; Google was four years away from existence; the iMac (1998) wasn’t even a gleam in Steve Jobs’ eye; Napster and the debate of internet piracy was still five years away; Facebook friends had to wait 10 years before they could be approved; and the ubiquitous video site Youtube was still 11 years prenatal. Sonic found a market before there was a market, banking on the global shift that the internet would bring and getting in on the ground floor on their own terms.

Jasper was 21 when he cofounded Sonic. He and Doty were in the SRJC’s burgeoning computer department, “doing things like hooking up a computer lab to the campus network, loading drivers on staff machines so they could connect,” says Jasper. Santa Rosa was also the first community college in the state to offer internet access to students. But even then, internet trolls and identity thieves popped up now and again.

“One of the customers was acting rudely” in a chat room, says Jasper, and was cursing at people through text on the screen. “Back then, I guess that was grounds for calling the school hosting the student,” he says with a smile, “back when the internet was a friendlier place.”

This particular customer didn’t seem the type who would act in this manner. It was discovered he was really a male high school student. “Through that we learned that accounts had been sold on the black market, so to speak—sort of a primitive identity theft.” says Jasper. “That was really what made me realize there was a commercial interest in internet access.”

HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT

At age 16, Jasper was done with high school. “You could take a test for a certificate of high school proficiency,” Jasper says, “so I didn’t graduate. Then I went and worked.” He took retail jobs not unfamiliar to teenagers, at places like RadioShack, Domino’s and Software Etc., all the while maintaining his interest in computers and bulletin board systems (BBS), a kind of primitive internet network popular in the early ’90s.

“When I was a kid, I had run bulletin board systems. Then when I was 17, I got a job working for a guy who had an eight-line BBS,” says Jasper. When he was 18, Jasper got a job helping students in SRJC’s computer lab before moving on to installation, mainframe and networking projects.

[page]

“I’ve known Dane since the ’90s,” says Dale Dougherty, a Sebastopol resident who started the nationwide Maker movement and founded MAKE magazine and Maker Faire. “Dane is representative of a small independent ISP who’s done really well by providing service and the kinds of support that people need,” he says. “I’m always rooting for people like Dane to succeed.”

Jasper’s honesty and candor when speaking about issues that many other companies dare not wade into is admirable. He doesn’t try to hide his business practices or opinions on issues in the industry. And he actually cares about his customers beyond just the bottom line.

Jasper was an outspoken critic of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) two years ago, in which the overreaching movie and music industries tried to pass legislation allowing for government takedowns of practically any site they chose, in order to curtail piracy. The legislation didn’t pass, thanks to wide public outcry and opposition from companies like Sonic, Google, Microsoft and others. It was apparent that legislators pushing for SOPA didn’t have enough technological knowledge to suggest such regulation, Jasper said in a 2012 interview on TechCrunch with Andrew Keen. “I think the answer is to make content available fairly and broadly.”

Regarding the current issue of net neutrality, Jasper himself has stayed fairly neutral. “It’s interesting to see the FCC’s attempt to take on the issues surrounding network neutrality, and they have been a bit clumsy about it,” he says. “The public has reacted in an unprecedented way to them.” That has, so far, included hundreds of thousands of letters, phone calls and emails to the FCC and a hilarious skewering by comedic news host John Oliver on his HBO show Last Week Tonight.

The reaction was set off by the FCC’s announcement that it would allow internet service providers to create a “fast lane” and a “slow lane” for internet traffic—in other words, to intentionally slow down connection speeds in order to charge customers and content providers, like Netflix, more money for the same service. “The worry is that service providers get so big that they can dictate the terms at which content reaches those customers,” says Jasper in a 2011 TWiT.tv interview with Triangulation host Leo Laporte. That could force customers to pay extra on both ends of the internet pipe. “Isn’t that frustrating?”

This illustrates the problem with the FCC’s plan: any ISP can choose to slow down or block content from any website it chooses, but can alleviate that congestion if a fee is paid. It’s the same tactic the mafia uses: “That’s a pretty nice front window you’ve got on your store, there, it would be a shame if, I dunno, someone were to throw a brick through it. We can make sure that never happens if you pay us a protection fee.”

This wouldn’t be a problem if there were more than three nationwide options for internet service. Sonic is one of the largest independents outside of Comcast/Time Warner, AT&T and Verizon, and it’s only available in 110 cities in California. “It’s good for Sonic if duopoly providers behave badly,” says Jasper, who speaks methodically with pauses just short enough to avoid awkwardness.

The majority of Americans only have two or fewer choices for broadband internet, and the federal government doesn’t foresee that changing much. The government’s National Broadband Plan website explains that it sees Sonic as the exception to the trend: “Building broadband networks—especially wireline—requires large fixed and sunk investments. Consequently, the industry will probably always have a relatively small number of facilities-based competitors, at least for wireline service.”

But Sonic signs up many new customers who are just fed up with the big three’s shenanigans. “We’re an example of how there can be more choices. You wouldn’t have a neutrality problem if you had a hundred Sonics,” says Jasper. “Availability of competitive access would solve the neutrality problem.”

[page]

PRIVACY, PLEASE

In 2011, Sonic fought a sealed court order to hand over records of one of its customers to the federal government. Jacob Applebaum, a Sebastopol resident and Sonic customer, was involved in the Wikileaks case. The fight, which Sonic lost, made national news after Twitter successfully petitioned to have a similar seal lifted.

“The orders to us in that case were, and are, under seal,” says Jasper, “so I’m not permitted to comment on that case.”

But even without comment, the statement made by Sonic’s action was loud and direct: we care enough about our customers’ privacy to fight federal requests in court. For a small company, that kind of statement makes waves, and for the past three years the Electronic Frontier Foundation has honored Sonic with a perfect score, the only ISP to receive such an honor. “We will review every law enforcement order we receive, and we will fight those where it is warranted to do so,” says Jasper. “We have demonstrated a willingness to do that. We are not a refuge for criminals or pirates. My goal is to protect the rights and privacy of my law-abiding customers.”

He points to Sonic’s size as a reason why this is possible. “When you’re a large internet access provider and you get 50 orders every day, you just have to minimize your cost of responding to those orders, whereas maybe we get one a week and we have the luxury of having a few moments to take the time and energy to look at each of these things critically.”

But as Sonic grows—it’s doubled in size in the past three years, an expansion to more than 200 employees—is that same commitment to privacy scalable? Jasper points to privacy commitments from large companies like Twitter, which also received a perfect rating from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Google, which has publicly fought government requests for data on its users.

SPEED OF GROWTH

In his 2012 TechCrunch interview, Jasper is quite candid about his business costs. “Internet transit is effectively too cheap to meter,” with most money going to “the interaction between us and customers,” he says, adding that Sonic spends almost 20 times more on customer care than actual bandwidth. “We make internet access; we make it out of ether. It’s not a natural resource.” And right now, Sonic is focusing on making that internet access a whole lot faster.

Here’s a quick history of internet speeds: In 1995, the movie Hackers features a scene where the characters geek out over a 33.6 kilobits per second (kbps) modem in a laptop. In 1998, DSL was introduced over phone lines, with a whopping

1.5 megabits per second (mbps), 45 times faster than that impressive Hackers modem. Sonic and others currently offer speeds up to 20 mbps, 13 times faster than original DSL, for less than what dialup used to cost.

Fiber internet, which is what Sonic has installed in Sebastopol and Brentwood in eastern Contra Costa County, is 1 gigabit per second—50 times faster than the current standard, and 29,250 times faster than the impressive 36.6 kbps from one year after Sonic was founded.

Maybe that’s why Jasper has a bronze cast of a cheetah, the fastest land animal, in full stride as one of the few decorations in his office. That, and it looks really cool.

Google chose Sonic as the contractor to install the first residential gigabit fiber service in California for its 2010 pilot program at Stanford University. Fiber is capable of much higher speeds than copper lines. Jasper couldn’t comment much on the project, citing Google’s privacy policies, but called it a “great opportunity.” Last year, Sonic installed gigabit fiber in downtown Sebastopol, where 42 percent of the city’s internet subscribers are Sonic customers, and is expanding this year to the outer reaches of the city.

Now it’s onward to Brentwood where Sonic has been digging up the streets and hanging cables in the air for a new fiber infrastructure to be activated later this year. Then it’s on to other cities, possibly Santa Cruz, Berkeley or Ukiah, where Sonic also has a high subscriber rate. Parts of Santa Rosa could be next too, says Jasper.

In February, Google identified San Jose as one of nine cities as potential sites for installation of its Google Fiber network. When this news was shared on Sonic’s web forum, Jasper, who comments with some regularity, responded to the idea that it is a “mixed blessing,” since Sonic is currently installing fiber in Brentwood and is looking to explore other cities in California. “The fibering of America is a decade-scale process, and there are plenty of communities to go around,” he writes. “They’ll build one, we’ll build another, etc. It’s a big task, and it makes sense that it will take multiple companies to achieve it.”