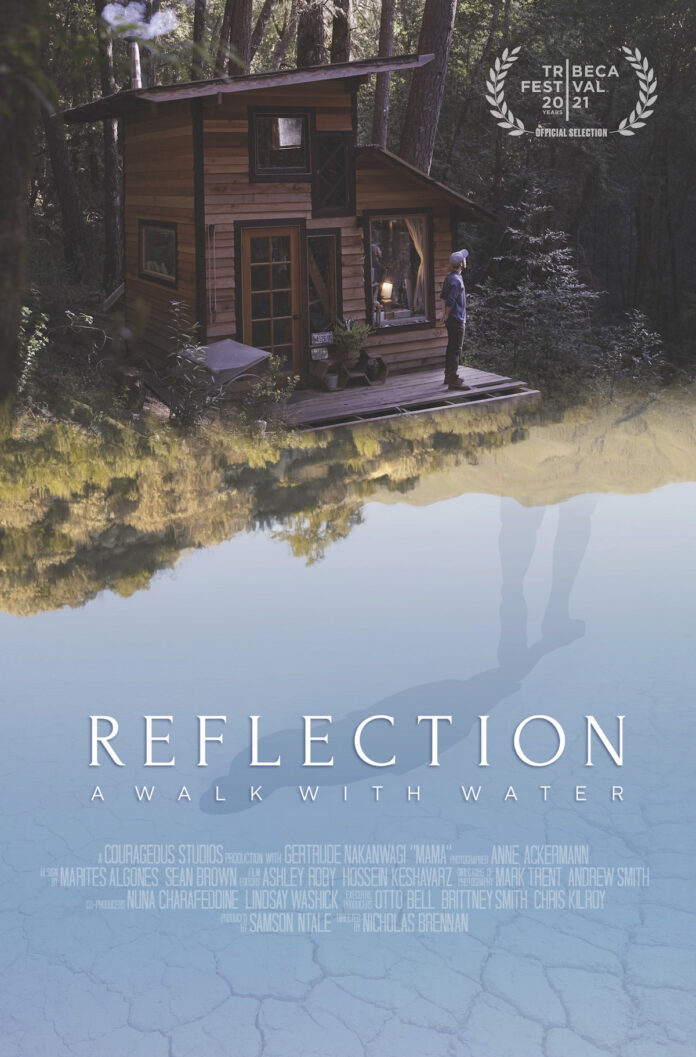

On a bright, blustery October day, a day that felt almost like normal fall weather, I had a conversation with filmmaker Emmett Brenner about his latest film, Reflection: A Walk with Water. In the film, Brenner and fellow environmental advocates walk the length of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to raise awareness about the misuses of water in California and the acute effects it’s having on the land. Brenner’s film informs, educates and empowers viewers. Reflection teaches about how water is moved, how that relocation affects the surrounding land and how short-sighted city planning results in shocking and avoidable water waste. It also shows ways, happening in real time, to resolve this mismanagement of water. During the hour and 19 minutes I spent watching Reflection: A Walk with Water, my mind was quietly and beautifully opened. I can’t recommend enough that everyone engage with this film and the insight it affords.

This discussion with Emmett was as much an appreciation of his work as it was two human beings considering the current state of humanity and our responsibility to participate in its fate. You, the reader, are also part of this dialogue.

Jane Vick: So I watched the film yesterday—

Emmett Brenner: Yay!

JV: Emmett, it was awesome! Really inspiring. My boyfriend and I were talking just the other day about how human beings develop systems. We identify—or create—a problem, endeavor to fix it and end up with another problem. A sort of teeter-totter effect ensues, searching for equilibrium between our innovative inclinations and pre-existing natural cycles. And when we pull away from the natural cycle in an attempt to manifest something on our own, things become destructive. If we used our abilities to steward the land in a participatory way, we could really get somewhere.

EB: Totally. And it’s incredible to me—we live in an unbelievably intelligent system, and all these things we create are attempting to accomplish tasks the natural world has for the most part already accomplished in more efficient methods than we could conceive of. But the beauty is that we don’t need to. We are a part of the intelligence of these natural systems, we have an opportunity to live human life in relationship with that intelligence.

JV: Reflection has so many inspiring examples of this relationship. There are so many brilliant minds in this film, sharing ways we can marry our ingenuity with natural cycles. It’s felt like a strange hubris has worked its way into the human dynamic, where instead of returning to the wisdom of the natural world to correct our missteps, we move further away.

EB: Right, yeah—the idea that natural methods of stewardship are “primitive,” as though that makes them ineffective. It reminds me of when colonizers came to the Americas; they described these landscapes proliferating with fruits and nuts and these incredible, old-growth trees. And they completely omitted—didn’t actually understand—that these places were being tended to by relationships with humans. These forests were being cultivated to have the abundance of food and life that they did. We can’t separate the “wild” as something other that we don’t belong within. We’re deeply connected. We’re part of the complexity of this whole system of life on Earth.

JV: Completely. I love the portion of the film that talks about thatch—tall grass growth, left untrampled—and how grazing elk would stomp it down until it lay flat on top of the soil, fertilizing it and aiding in water transfer, thus avoiding fire conditions. It makes me think about places like Spring Lake, where they now bring goats in to take care of the overgrowth to reduce fire risk. The fires really woke us up.

EB: It’s a struggle in this era of ownership and privatization, when landscapes are cut into boxes. The natural movement of wild grazers is significantly impacted, and it puts much more emphasis on our management of domesticated animals for the time being. We need to look to the patterns of those wild animals in our management of domesticated ones. I’m glad the fires are waking us up in this way … it’s troubling that it takes such catastrophe to initiate change.

JV: Do you harbor concerns about our future in that way?

EB: I do. On a personal level, my patterns and addictions to technology, the role it plays in my life, concerns me greatly. I don’t know fundamentally where we’re heading, and in order to be resourced with hope I feel that I need to be tending my own relationship with life and love and land. When I’m wrapped up in my phone I feel farther away from that tending. Farther away from the resources to feel possibility and hope. I feel most capable of facing the context of these times when I am present in a quieter way.

JV: I also frequently confront my own struggle with technology. Trying to gauge an appropriate level of use, wanting to be involved in contemporary society and experiencing incredible anxiety and confusion as our neurochemistry and societal practices change. And it’s true, we don’t know what will come of humanity, or Earth. I think the things we engage in—sometimes benign, sometimes malevolent, often both—must be recognized as imperfect attempts at a cohesive existence. We can’t completely reject what is—i.e. tech, now clearly a part of our lives—we can only continue engaging with our circumstances and ask when things feel wrong and when they feel right. That’s how I deal with so much change and challenge. There’s immense mystery to it, much we can’t explain, but still we engage in real time.

EB: It’s true. Humans struggle with mystery—when we approach something that carries a feeling of not knowing we tend to tighten, to turn towards control and the pretence of knowing. We try to define anything that our mind can’t fully wrap around—to take it apart and categorize it. But we lose the whole picture this way. It’s how we’ve treated water. Water is way more mysterious than we can fathom, so intricately involved in every system, and we’ve done everything we can to control and manipulate it, to devastating outcome. We try to dominate the unknowable instead of finding our place within it.

JV: Right. We forget that we are participating, not directing, and then the balance and understanding are lost. We need active participation in life, but we can’t override it; we have to operate within the larger system.

EB: Exactly. It can’t just be inquiry and openness, nor domination and control. It’s the balance that produces something lasting.

JV: And we have the capacity within us. Reflection is a beautiful testimony to that capacity.

Reflection: A Walk with Water is currently showing at the Mill Valley Film Festival, and tickets can be found at mvff.com. Please take your time with it, and foster a sense of hope for our future.