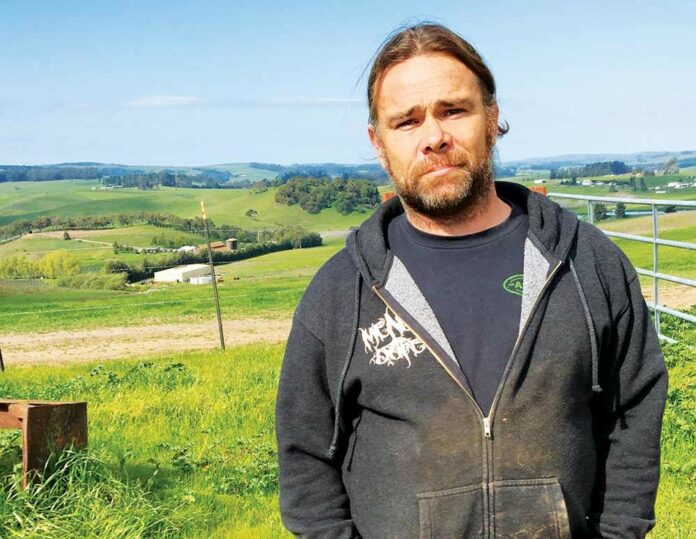

Soon after California’s Department of Public Health lodged cannabis-industry laborers on the state’s “essential workforce,” and therefore not required to stay at home, David Drips, 39, and his business partner, Zac Hansen, 28, began performing essential tasks on a windswept, 300-acre farm in West Sonoma County.

The fierce wind, along with county regulations and regulators, seems to have given Drips and Hansen more trouble than the coronavirus, at least so far. Neither of them has been physically ill.

At 410 feet above sea level, I had a spectacular view of Sonoma Mountain, Taylor Mountain and the Cotati Grade on Highway 101.

Drips sat down, rolled a fatty, fired it up and inhaled. If he was stoned, I couldn’t tell. I didn’t need his joint, and wouldn’t have taken it even if he had offered.

In a text that morning, my friends at the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) urged me and all cannabis consumers not to share pipes, joints and bongs, and, if-and-when possible, to turn to tinctures and edibles since they don’t stress lungs. Those NORML friends also urged the use of 90-percent-plus Isopropyl Alcohol to rid germs and pathogens from delivery systems.

Before I met with Drips and Hansen, I bought gummies at my local dispensary, and after consuming just one I was high. Tens, if not hundreds of thousands, of other Californians were also high. In the wake of the virus, cannabis sales have boomed, according to one source, by more than 200 percent. Last year legal cannabis sales in California topped $3 billion, while the illicit market came in at just under $9 billion.

Drips and Hansen, both in T-shirts and jeans, started their business on Petaluma Hill Road. Hence the name of their company, “Petaluma Hill Farms,” which they’ve retained, though they were forced to move to Two Rock Road where there are more rocks and cattle than human beings.

“We were fucked by the Sonoma County Planning Department,” Drips says. “We understand the need for some rules, but the county has used too big an axe, so a lot of my friends have been cut out of the industry. The only option for Zac and me has been to adapt. We moved from a parcel zoned RR, or “Rural Residential,” to LEA, or “Land Extensive Agriculture District.”

The 300-acre-parcel is well suited for cannabis. There are no schools or school kids nearby, and no next-door neighbors who might go to court to stop them. The cannabis garden itself is set back 900 feet from the road. There are no creeks to protect and no trees that might need to be chopped down to provide more sunlight.

“We have all the sun we need,” Drips says. “Plus good soil and lots of clean water. That equals good marijuana.”

Drips isn’t your ordinary California pot farmer, though few—if any—pot farmers are “ordinary.” Over the past 40 years, I have met scores of them: the law abiding and the outlaws, the environmentally conscious, the greedy and the compassionate. Drips keeps on keeping on and abides by best industry practices. Hundreds, if not thousands, of growers—some of them his friends—once cultivated modest commercial gardens in and around Sebastopol and were pushed out by legalization, taxation and regulation.

“I have faith in what we do at our farm,” Drips says. “I believe in marijuana sociologically, economically, medically, spiritually and more. I can’t see doing any other job, though I have worked in construction.”

Hansen adds, “I love this work.”

A graduate of Rancho Cotate High School, where he played lacrosse, Hansen has grown cannabis ever since he turned 16. His 8-year-old daughter attends school in Rohnert Park, his hometown.

Like Hansen, Drips knows and loves Sonoma County, though he was born in Stockton, has traveled widely and has lived in Louisiana, Florida and Virginia.

“America is a beautiful place,” he says. “Though there’s no place more beautiful than here.”

What makes Drips stand out more than anyone else in the field of marijuana cultivation is that he served for five years in the U.S. Navy, and was deployed in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“The military helped me to grow as a person,” he says. “I visited 23 different countries and acquired a foundation of knowledge.”

Sonoma County officials may not know his military background and training. He doesn’t brag about it, though he’s not hiding it either. Assertive without being aggressive, he’s ready to fight the good fight.

“The county is waging a war of attrition against marijuana growers,” Drips explains. “They want us to fail. They hope that we’ll pack up, clear out and not come back.”

Drips says he has no beef with most of the county supervisors, including Linda Hopkins, Shirlee Zane and Susan Gorin. He’s attended enough meetings to know them and he’s spoken out so often that he’s made a name for himself as an advocate for the cannabis industry. But let’s be absolutely clear: He doesn’t appreciate the folks at Code Enforcement who have hammered away at him and at other growers sometimes, it seems, just to be ornery.

Drips has had a series of verbal skirmishes with officials who want him to jump through one hoop after another: build a fence, plant trees to hide the fence, pave a road in case of fire and more.

Drips hasn’t minded spending money on essentials at Friedman’s Home Improvement and Harmony Farm Supply & Nursery, and paying Weeks Drilling and Pump for a well. In fact, he points out that he and his fellow marijuana farmers have helped to keep local businesses afloat through drought and fire.

“I have not taken any corporate investment,” Drips says. “It’s all personal savings, though a friend gave me a $30,000 personal loan.”

He’s received counsel from a half-dozen lawyers, including Joe Rogoway, Omar Figueroa and Lauren Mendelsohn. Drips and the growers who have his back, as he has theirs, recently revived the dormant Hessel Grange, which now, for the first time, has an emphasis on cannabis farmers and farming.

“Some of us feel like we’ve been denied our basic rights,” Drips says, “But we still believe in the American Dream.”

His son Donough attends elementary school and his stepson Joshua goes to high school. Drips would like them to inherit the business and become farmers.