Nearly two decades ago, I somehow convinced my filmmaking pal, Abe Levy, to accompany me on a drive across the American Southwest, through the endless ribbon of mirages known as Interstate 40 until we reached the White Sands Missile Base in Socorro, N.M.

This was not our final destination, but an obligatory stop made on behalf of the U.S. government so that they could clear our rental car, our camera gear and our very persons before granting passage onto the base. After that, we drove 17 more miles into the base’s interior, then rendezvoused with a press liaison who drove us further still.

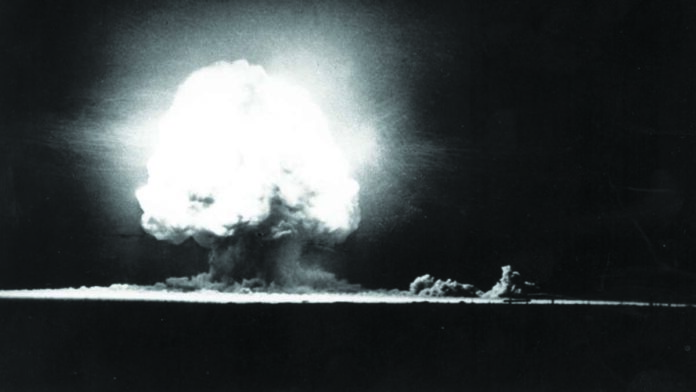

Levy was the cameraperson and I was the reporter, and our story was pegged on the 60th anniversary of the first detonation of the atom bomb. The subject had haunted my imagination since sixth grade, after I managed to miss the broadcast of ABC’s dystopian TV-movie about nuclear war, The Day After. In its absence, during the morning’s class discussions intended to soothe our anxious minds, my own nuclear nightmares filled the void.

At the end of the original broadcast, a disclaimer read, “The catastrophic events you have just witnessed are, in all likelihood, less severe than the destruction that would actually occur in the event of a full nuclear strike against the United States.” Naturally, this added more fuel-rods to the reactor fire of the Thanksgiving holiday, when families all across America shared solemn conversations about vaporization, radiation sickness and—oh, no!—hair loss, as the gravy boat dolefully bobbed around the table.

Not my family, of course—we missed it. But I knew what had happened on TV, if only secondhand, and that it was “less severe” than the real deal, which then seemed imminent.

Fortunately, President Ronald Reagan commanded Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall!” and I guess he did, because Jesus Jones made a music video about it, and my nuclear holocaust anxiety quelled into a low thrum through the ’90s. By 2006, I was able to confront the nearly forgotten fear at its literal genesis—the Trinity site in New Mexico—recorder in hand, as Levy popped off shots. I wrote and filed my story, and it eventually became yesteryear’s news.

Since then, not even North Korea’s nuclear-saber rattling during the early provocations of Donald Trump’s presidency resurfaced my atomic anxiety—though nicknaming Kim Jong-Un “Rocket Man” was, dare I say, inspired. No, it took filmmaker Christopher Nolan and his Oppenheimer marketing machine to flare up this radioactive half-life within me. But it’s not anxiety anymore; it’s angst. And I suppose it will always be there, like the shadows etched into the stone walls of Hiroshima by the boiling light of Little Boy. After 40 years, it’s an old friend. I suppose this is how we learn to stop worrying and love the bomb.

Read ‘Atomic Hangover’ at dhowl.com/bomb. Originally published at dhowell.substack.com.