If Scott Heath has harvested a bitter fruit from his labors, that’s just the way he planned it.

It’s late July, and the apples are ripening in Heath’s two-acre experimental orchard on Gravenstein Highway north of Sebastopol. Heath plucks an apple from one of the head-high trees, and I follow suit. It’s a good-looking fruit, plum-red and smooth-skinned. But when I take a bite, tannins dry out my tongue. This apple’s got more grip than a Rutherford Cabernet Sauvignon.

“That’s why they call them spitters,” Heath says.

These aren’t your granny’s baking apples. But they are an essential ingredient for making traditional and European-style ciders. Access to these varieties will be critical, some say, for local craft-cider makers hoping to compete in an increasingly crowded category.

Ask around about craft cider in the North Bay, and most everyone will mention Tilted Shed Ciderworks, co-owned by Heath and his wife, Ellen Cavalli. When they made their debut at Sebastopol’s annual Gravenstein Apple Fair in 2012, they were squeezed into a corner of the wine tent. At this year’s fair, running Aug. 8–9, eight local cideries will share space in the “craft cider tent.” (See page 23 for more on the fair.)

JUICE INTO CIDER

Craft cider is hard cider, fermented from apple juice to a strength of 6 to 7 percent alcohol, and often higher. According to Tom Wark, author of the Cider Journal blog (ciderjournal.com), the cider category grew by

70 percent in 2014. Behemoth brand Angry Orchard, made by Boston Beer Company, accounts for more than half of sales, while Stella Artois, Samuel Smith and others have made a bid for the apple-flavored action.

Craft producers represent a very small slice of the pie. While the rise of cider generally is linked to the success of craft beer, and to its appeal as a gluten-free alternative to beer, craft cider has more in common with wine.

Heath compares cider apples to Vitis vinifera, the species to which nearly all grape varieties used for making wine belong. The better wines are not made from grocery market grapes like Thompson seedless; they’re made from specialty winegrapes, grown in the right regions. “We think cider is exactly the same,” Heath says

Heath’s orchard includes “bittersharps” like Kingston black, an English variety that’s highly valued because of its combination of high acid and high tannin. The “sharps” include local hero the Gravenstein, favored by pie makers for its high acid and low tannin. It makes pretty good hard cider as well, but it lacks the high tannins that “bittersweets” like Muscat de Bernay and Nehou contribute to a cider’s structure. Some “sweets” like Roxbury russet wouldn’t look pretty in the produce aisle, but provide sugar that approaches winegrape levels.

Most cider on the U.S. market is not made with such apples.

[page]

APPLE ECONOMICS

“There are a lot of orchardists looking at the cider market,” says Wark. “They can get more per ton in heirloom or cider apples. In Sebastopol, they’re up against Washington, they’re up against China. It’s easy to understand why they pull up their apple trees and plant Pinot Noir.”

The value of the 2013 winegrape harvest was over $605 million, according to the Sonoma County Agricultural Commissioner’s crop report. Apples brought in less than $6 million.

In what might be a sign that the market is heating up, Heath won’t name his growers on the record, out of concern that other Bay Area cideries are scoping his apples. “It’s really getting competitive at this point,” Heath says. But he can’t think of a grower who’s stayed in the business specifically for the industry. “That’s what we had sort of hoped to achieve.”

To that end, Tilted Shed offered growers a better price than that offered by Manzana, the only apple processor left in the area. But to be fair, other than Gravensteins, Manzana doesn’t buy heirloom apples favored by cider makers.

“From what I understand,” says Heath, “it was about the same as they were paying in 1976.” And Tilted Shed would pay a lot more for cider apple varieties, Heath adds, with a caveat: “But you can’t even get a ton around here, so it’s just theoretical.”

A FAMILY BUSINESS

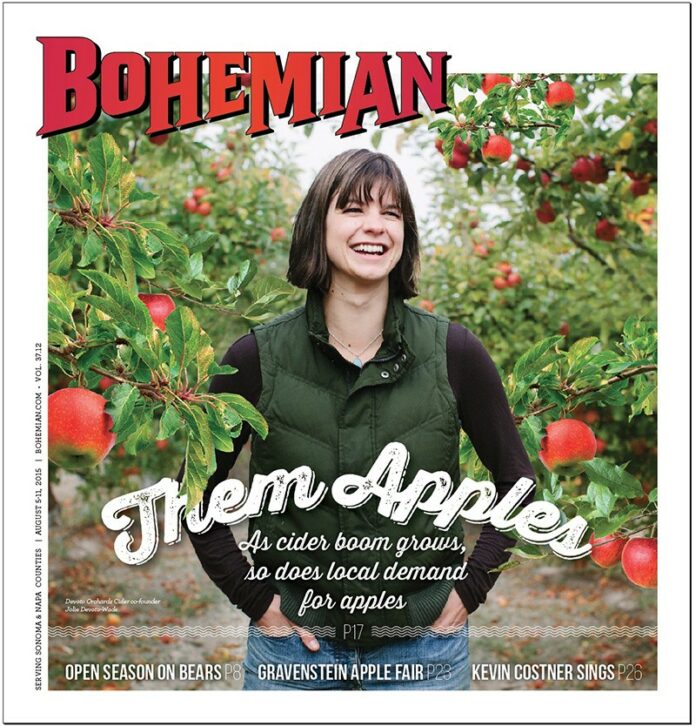

Six miles to the south, Stan Devoto farms a hundred varieties of apples in the same sandy, Gold Ridge soil. (Hedging his bets, he also grows Pinot Noir.) Much of the produce is sold to restaurants and a fresh market that pays a premium for top-grade apples. His daughter, Jolie Devoto-Wade, then gleans the odds and ends to make her 4,000 cases of Devoto Orchards Cider.

“Yes, someone planting a cider apple orchard would get a significantly better price,” Devoto-Wade says. “But the market definitely likes ciders that aren’t so intense. I think the general palate would probably prefer ciders that are made with a little bit of cider apples, and then some others.”

In 2012, the Devotos planted an experimental acre of English and French bittersweets and bittersharps. Many of these have never been grown commercially in this area, but if one doesn’t work out, they can simply graft over the tree to one that does better.

The bill payer is Golden State Cider, a can and keg brand that Devoto-Wade owns with her husband, Hunter Wade. They’ll ship out 100,000 gallons this year, made from California and Washington state Golden Delicious, Granny Smith, Fuji, Pink Ladies, apples you’d encounter in the supermarket produce section.

Still, Devoto-Wade says there’s a lot of demand for the heirlooms.

“A few farmers grow them, and I see more being planted every year,” she says. “And we’re getting away from the Red Delicious mentality, which I’m very happy about.”

APPLES OR GRAPES?

Asked if craft cider is a boom or a boomlet, longtime apple farmer Paul Kolling opts for the latter characterization. “I’ll believe it’s a boom when they start ripping out vineyards and start planting apple trees, instead of the other way around,” he says.

As majority owner of Specific Gravity Cider, Kolling is banking on cider. But it’s only a fraction of his other business, Nana Mae’s Organics, which sells 100,000 gallons of organic apple-cider vinegar each year.

Thus far, since the local crop is treated as a commodity that competes with Washington apples, Kolling has just kept the orchards he tends going with interplantings of various kinds of apples. And he’s not convinced that cider-apple varieties have much on the old Gravenstein.

Mark McTavish says he gets all he needs for complex, wild-fermented cider from the ghosts of Sebastopol’s original apple boom.

[page]

Based in Southern California, McTavish is the owner of Troy Cider. Troy Carter started the brand three years ago. Carter is a niche-wine market adventurer who asked landowners for permission to forage apples from abandoned orchards. McTavish claims that many of these apples-gone-wild are perfectly tannic crabapples, from seedlings sprouted among the original trees. He also uses quince, a relative of the apple that he calls the jewel of the cider world.

“We just make a really complex, funky cider which is unlike any that I’ve ever had,” McTavish says.

Foraging in the land of the lost apple tree will only take the industry so far. Even McTavish has to supplement his 1,500 cases with purchased organic apples.

Chris Condos says he pays a bit more for certain apples, up to $1,000 a ton. Condos and his wife Suzanne Hagins are winemakers, but they recently added 500 cases of cider to their Horse & Plow label.

Most of the apples come from their neighbor’s property two doors down. “It’s nice supporting people who have held on,”

Condos says. “When they were getting $150 a ton for apples, it was tempting to move on—especially when Pinot Noir, in good locations, is selling for $6,000 a ton,” Condos says. “Apples aren’t there yet, but I think they’re headed in the right direction.”

APPLES TO APPLES

Don’t do the math yet, because there’s something missing from the equation: you get more apples per acre than grapes. While Kolling says he’s getting three tons per acre from old, dry-farmed orchards, that’s at the low end for other growers.

“If you have irrigation and you do a really good job, you get 30 tons to the acre,” says Paul Vossen, Sonoma County farm adviser for University of California Cooperative Extension. “And I know of a grower up in Alexander Valley who got 63 tons.” Those figures are extremes, Vossen cautions. “You wouldn’t bank on that. But even dry-farmed, you should be able to get 15 tons to the acre.” That syncs with Devoto-Wade’s figure of 12 to 15 tons from her family’s dry-farmed orchards.

An acre of grapes grown for the premium wine market in Sonoma County yields about two to four tons. A ton of Pinot Noir fetched an average price north of $3,200 in 2014; Chardonnay, about $2,000.

Do that math, and the prospect for $1,000 heirloom apples looks a little better—on paper, anyway. Still, there’s something missing: how does the pressed juice yield compare?

“It is shockingly comparable,” says winemaker Condos. “You get anywhere from 145 to 165 gallons per ton.”

This February, Vossen held a seminar intended to get vineyard operators to at least think about diversifying with cider apples. He says there’s a good reason that producers, and ultimately consumers, might want to pay more for this specialty crop.

“You get slow ripening in Sonoma County,” Vossen explains. “Basically, it’s that same temperature regime that produces some of the really good flavors in winegrapes.”

Following up on his success advocating for olive trees, Vossen is helping to plant a demonstration cider apple orchard at Santa Rosa Junior College’s Shone Farm.

Vossen compares the fledgling cider apple business to the now-dominant viticulture, back when orchardists were taking a look at what newcomers were doing with Pinot Noir.

“It took them a while,” Vossen recalls. “They looked at that and said, ‘Gee, maybe I could do that, too.’ Now most of the apple growers are also grape growers. It didn’t happen overnight.”

APPLE RENAISSANCE

It took newcomers like Joseph Swan to reinvigorate the Russian River Valley wine industry. In 1968, Swan made some Zinfandel from a heritage vineyard on his property, a relic from a wine boom of the previous century. Then he turned his Eurocentric attention to a rare variety, almost unknown to the area: Pinot Noir.

Nobody is predicting rampant success for cider apples, and potential growers are sitting on the sidelines, unsure whether the trend will last. Indeed, Tilted Shed’s greatest treasure, the “lost orchard” they discovered, also serves as their cautionary tale: the cider visionary who planted these true cider varieties abandoned it some 30 years ago.

Heath hopes that his orchard might serve as an incubator for the industry, helping with scion wood and local knowledge on which varieties do well here. With such diligence, this eclectic mix of little apple trees among the grass and weeds just might be the “Swan vineyard” of the future of craft cider.