In November of 2011, Mark Herczog wrote a short, desperate note on his calendar for the week of the 21st. It was about his son.

“It said, ‘Get help for Houston,'” his sister Annette Keys recalls.

It had been an increasingly difficult year for the Herczog family, during which 21-year-old Houston seemed to have been replaced by a different person. He had always been shy, but according to his aunt, he now shunned social interaction, waiting until after 11pm to go to the gym so he could work out alone. He stole his mom’s Adderall. He said strange things with an empty, vacant gaze that his family now refers to as “the look.” In early November, when he crashed his dad’s green Caravan and smashed his head into the windshield, he didn’t check to make sure his passengers were OK. Instead, his aunt, who was in the vehicle at the time, says he asked her about the sandwich he’d placed between them, in the center console of the car.

Houston’s family knew something was very wrong, but they didn’t know what it was. They didn’t know that three psychiatrists would eventually diagnose him with schizophrenia. They didn’t know that two of them would be appointed by Sonoma County Superior Court.

Around 1am on Nov. 21, Houston Herczog stabbed his father in the kitchen of his Rincon Valley home, using at least four knives to gash and puncture his body 60 times. He tried to cut off his head. He would later tell a court-appointed psychiatrist that he’d thought he was performing an exorcism with a cardboard version of his dad. When police arrived, he told them flatly, “I killed him.”

Mark was declared dead at 2:52am by Memorial Hospital, his face so tattered that, according to the coroner’s report, his right ear was barely attached.

He was never able to help his son.

Houston’s defense has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, a verdict that would likely allow him to be sent to a maximum-security facility for the criminally insane, such as Napa State Hospital. Three psychiatrists have backed up this claim. On the eve of Houston’s juried trial, however, the district attorney called for a rarely requested additional opinion, which contradicts the others’ assertions of insanity.

Herczog faces a possible murder charge that could land him in prison, where his family worries he won’t have access to the treatment they believe he needs.

Tragically, the Herczog family has landed in the criminal justice system partly because of their initial reluctance to use it. In 2007, Sonoma County police shot and killed 16-year-old Jeremiah Chass and 30-year-old Richard Desantis during psychotic episodes. Mark Herczog’s daughter, sister and ex-wife all say Mark refused to call police despite signs of Houston’s escalating violence for fear that officers would shoot his son.

As a judge prepares to sentence Houston in a Sonoma County courtroom, Mark’s surviving family is not crying for blood. Instead, they want treatment for Houston and changes in a system that too often criminalizes—and even kills—the mentally ill.

‘I’M SCARED’

Cameron McDowell, Mark’s oldest daughter, remembers a chilling moment of foresight soon before her dad was killed. At her home in North Carolina, she’d just gotten off the phone with her aunt, who’d described the vacant look that would slip over her half-brother sometimes, saying it almost seemed like he left his body and someone else came in and took his place.

“I told my husband, ‘I’m scared Houston is that kid who’s going to walk into a supermarket and open fire,'” she recalls.

This was in mid-November, but she’d suspected something was off for roughly a year and a half. The brother that she describes as shy, creative and gentle as a child had become quieter and more distant. He’d quit his band and instead spent hours playing guitar alone. McDowell’s dad once told her jokingly on the phone that her brother was such a loner, he wished Houston go out drinking if it meant he’d be with friends. On her son’s third birthday, McDowell received a card from the family that Houston had signed, “I hope you have a shitty birthday.”

McDowell wasn’t alone in her concern. Her aunt, Annette Keys, noticed him changing in 2010, after he graduated from Santa Rosa High School’s ArtQuest program and began taking classes at SRJC. He read Kant and Nietzsche obsessively. He would begin a movie with the family and then get up 30 minutes later to go sit by himself at the computer without explaining why.

Keys lives in Ohio, but she came to Santa Rosa to visit her brother Mark in early November, when she was in the car accident with Houston. On Nov. 11, the day before she flew back to Ohio, she asked Houston about the change she noticed in him.

“I said, ‘Honey, I feel like something happened to you. Did something happen that you’re not telling us about?’ And he gave me this sideways glance and said, ‘Maybe I’ll tell you about it sometime.’ It was the creepiest thing.”

In March of 2011, Houston’s mother and Mark’s ex-wife Marilyn Meschalk-Herczog began taking her son to see a private psychiatrist, Dr. Dennis Glick. Like other family members, Marilyn was increasingly concerned about her son. He was argumentative. He couldn’t keep a job. He would act out in bizarre ways, like refusing to follow his employers’ dress code.

The three psychiatrists who assessed Houston in jail reviewed Glick’s notes, which suggest several possible diagnoses for the then-20-year-old Houston—major depression, developmental issues and schizoaffective disorder. According to Dr. Alan Abrams’ review of Glick’s notes, the initial psychiatrist did not recognize that Houston was suffering symptoms of schizophrenia, despite his early note on schizoaffective disorder, and focused instead on his depression, prescribing him an antidepressant.

Glick also noted Houston’s substance-abuse history, which he writes included Adderall that Houston stole from his mom, along with alcohol, LSD, marijuana and other prescription medications. In his interview with Dr. Abrams, Houston said that he only took LSD once, in the ninth grade, and in his interview with Dr. Donald Apostle, he said he smoked pot in high school but stopped in the summer of 2009 because it made him feel psychotic. According to the review of Glick’s notes, Houston stopped taking Adderall—after being prescribed an antidepressant—until June, with sporadic use through September.

Because Houston continued to steal his mother’s Adderall, Marilyn eventually told him he needed to leave her Forestville home and live with his dad. But on Nov. 19, she says, two days before he killed Mark, Houston came back to her house.

“He had that look in his eye, and he said, ‘I feel really violent,'” she recalls. “I said, ‘Are you afraid you’re going to hurt me?'”

Marilyn says that she followed Houston through her home, out to the attached garage. As she descended the steps leading into the garage, her son grabbed her by the arm and threw her. Then he locked her in, asking her through the door if she was afraid of him.

“I said, ‘No. You’re my child. I love you and I trust you, and I don’t think you’re going to hurt me,” she recalls, crying.

“I had told him, ‘If you’re feeling violent, go out and run. Run around. It’s dark out and nobody will see you. Just run as fast as you can. Go up the hill. Just run.'”

He unlocked the door and ran outside the house. In an interview with Dr. Abrams recounting the same night, Marilyn says that when she checked her purse, more Adderall was gone.

[page]

‘DON’T CALL THE POLICE’

After he threw her across the garage that night, Marilyn says that she called her therapist, who told her to call the police.

In California, officers can take mentally ill people who are a danger to themselves or others into temporary custody in what’s known as a 5150, or involuntary psychiatric hold.

She called her ex-husband and told him what her therapist had said. “He said, ‘No, no, please don’t call the police,'” she recalls. “I said, ‘Why not?’ And he said, ‘They shoot those kids. Please don’t call them. That’s my son.'”

Mark’s sister and daughter report similar conversations. Both say that when the idea of a 5150 was brought up, Mark insisted that the family refrain from calling the police. McDowell says that in October, her dad told her he’d looked into an involuntary psychiatric hold.

“He said that there had been some cases where parents had done a 5150, and the police have shot and killed their kids,” she says.

In Sonoma County, two mentally ill individuals died after their families made distress calls to local law enforcement. During a 2007 psychotic break in which he sat on his little brother clutching a two-inch Leatherman knife, 16-year-old Sebastopol resident Jeremiah Chass was shot 11 times by the sheriff’s deputies who answered his mother’s distress call. He died in their driveway.

A month later, bipolar 30-year-old Richard Desantis was also shot as he ran out of his house toward the sergeant and two Santa Rosa officers who responded to his wife’s call. According to the Desantis family’s attorney, he was unarmed when he was shot. He also died in front of his home.

Not long afterward in January 2008, 24-year-old Jesse Hamilton, suffering from schizophrenia and holding a butcher knife, was shot and killed by a Santa Rosa police officer after a staffer at his group home called 911.

While few national statistics on the subject exist, the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center reports that police kill mentally ill people in so-called justifiable homicides four times as often as they kill people who are not mentally ill.

According to McDowell, her father told her in October that he was too unsure about what Houston might do if he called the police, and that he didn’t want to lose his son.

INTO THE NIGHT

Several hours before Mark died, Marilyn says that her youngest daughter, 17-year-old Savannah Herczog, called to warn her that the strange, vacant look was coming over Houston again. She recalls thinking that he might come over to her house, safe in the knowledge that she had changed the locks.

The next phone call Marilyn received was after midnight. It was her daughter again, saying that Houston had stabbed their father.

Marilyn says she raced to Rincon Valley, still unaware of the magnitude of the crime. She remembers thinking the attack had probably resulted in some kind of minor injury, like scissor wounds in her ex-husband’s arm. But as she approached Mark’s Parkhurst Drive home, she saw police cars and paramedics surrounding the yellow house with brown trim. She says that her daughter ran into her arms, crying. She told her that Mark had been taken away, and that he hadn’t been moving at all.

The two women were taken into police custody for questioning. Several hours later, still in custody, they learned that Mark was dead.

After she was let out of police custody, Marilyn says that she went back to the house and went inside. The kitchen walls were covered in blood. She saw a denim jacket sitting on the back of a chair that was also covered in splatters of blood. She picked it up and put it on.

According to Mark Herczog’s autopsy report, a chop wound on his scalp exposed his skull. His left eyelid was punctured. Most of his right ear dangled from his face. Ten horizontal, overlapping stab wounds surrounded his neck just above his thyroid, where Houston tried to remove his head. His entire body down to the soles of his feet was covered in blood.

McDowell says the condition of Mark’s remains meant she wasn’t able to say goodbye to her father’s body; although she flew to Santa Rosa from North Carolina, she had to say goodbye to his hand. She remembers entering the funeral home, where her dad had been laid out in a body bag with one scratched-up hand poking out. A flesh-colored blanket had been draped over the body bag. She remembers thinking that it looked oddly like a Muppet, and that because her dad had a twisted sense of humor, she felt like he was with her as she had this thought.

[page]

‘OH, DEAR. OH, GOD.’

Three psychiatrists have diagnosed Houston Herczog with paranoid schizophrenia, arguing that he killed his father in the midst of a psychotic break.

As Dr. Robbin Broadman writes: “There is no non-psychotic motive that I can see for the violence that occurred. He and his father may have had a disagreement, but the extent of violence goes beyond what one would expect from a stabbing in anger. There were 60 stab wounds.”

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) defines schizophrenia as a chronic brain disorder that afflicts roughly 1 percent of the American population. It stems from a combination of genetic and environmental factors, and is often characterized by paranoia, hallucinations and a lack of interest in socialization. It typically exhibits between the ages of 16 and 30. Although NIMH cautions that most people with schizophrenia are not violent, certain tendencies, like delusions of persecution, can lead to violence.

“If a person with schizophrenia becomes violent, the violence is usually directed at family members and tends to take place at home,” NIMH’s website states.

Considering the match-up between Houston’s behaviors the year before he killed Mark and his ongoing paranoid delusions in prison—of everything from TVs speaking directly to him to the prison being a concentration camp—Dr. Abrams writes in a report dated Nov. 1, 2012: “With a very high degree of medical certainty, I believe that Mr. Herczog was insane at the time of the killing.”

Dr. Abrams was retained by Houston’s defense, public defender Karen Silver, and the two psychiatrists brought in by the impartial court agreed. Dr. Donald Apostle and Dr. Broadman examined Houston in reports dated Dec. 3, 2012, and Feb. 18, 2013, and both concluded that a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity is applicable. Along with Houston’s behavioral patterns and the sudden and gruesome nature of his crime, the psychiatrists also interviewed him about what he believed was happening while he was stabbing his dad. The two accounts match up: he thought his father was trying to speak metaphorically to him about incest. He says he thought his dad was speaking symbolically and “in code.”

“Evil was frantic, squeezing my mind. I had to stop it. It wasn’t my dad,” he told Dr. Broadman.

Houston told Dr. Apostle that was when he grabbed a knife and began stabbing his father, who seemed to him to be plastic and unreal.

Both psychiatrists note that Houston was shaking while he talked. Dr. Apostle writes that after recounting the stabbing, he stopped, sighed and said, “Oh, dear. Oh, God.”

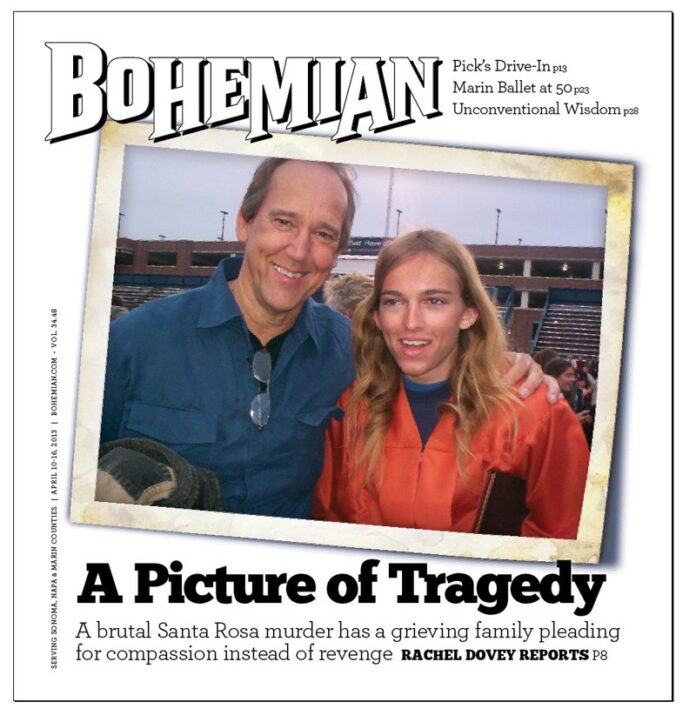

Silver declined the Bohemian‘s request to interview Houston in jail. At a court appearance on March 29, he stared at the ground, his shoulders hunched, and rocked slowly back and forth. His hair was short and unkempt and he wore glasses that he kept pushing up as they slid down his nose. He was unrecognizable from the thin, smiling boy with high cheekbones and wavy, blonde hair who hugged his smiling dad in graduation photos from 2010.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness’ (NAMI) jail liaison Carol Coleman agrees with the three psychiatrists, based on her contact with Houston beginning in December of 2011, soon after he was jailed. She asked that the Bohemian clarify that she was simply speaking from her own experience and not as an official spokesperson for NAMI.

Coleman recalls that Houston’s symptoms in prison were indicative of paranoid schizophrenia. She describes him as shy, depressed and traumatized, and speaking in disjointed sentences.

“I really believe, from my gut, from my background, from my experience, from my expertise, that Houston is mentally ill,” she says. “I believe that he does not belong in a prison. He really needs help and belongs in a hospital where he can get help with his mental illness.”

TRIAL AWAITS

Despite the opinions of three psychiatrists, an insanity defense can be a tough sell. A 1991 study commissioned by the National Institute of Mental Health and published by the Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry found that less than 1 percent of county court cases involved the insanity defense, and, of those, only around one in four was successful. The nation’s jail cells now contain up to 400,000 mentally ill, according to NAMI, which estimates the cost of housing nearly half a million mentally ill to be $9 billion a year.

In California, defendants cannot have committed their crime under the influence of drugs or alcohol when pleading not guilty by reason of insanity, a detail that is being debated in the Herczog case.

In his blood sample at the time of arrest, Houston tested positive for amphetamine and dextromethorphan, two common ingredients in cough syrup. He also reported that he’d continued to take Adderall.

Shortly before press time, the deputy district attorney prosecuting the Herczog case, Robert Waner, received a fourth doctor’s report from Dr. James Misset. While district attorney spokesperson Terry Menshek declined to discuss the document with the Bohemian, the Press Democrat‘s Paul Payne reports that Misset’s evaluation concludes that Houston was acting under a drug-induced psychosis and not a mental illness.

The two court-appointed reports do discuss Houston’s drug use when he killed Mark.

“He did use Adderall, but his drug level was insignificant, and the duration of his psychosis both preceded and continued after his relative cessation of Adderall use,” Dr. Apostle writes.

Dr. Broadman writes that although Houston’s drug use may have exacerbated his psychotic symptoms, “it is clear that he was having hallucinations and delusions before the drug use began. His symptoms were chronic and escalated over a period of time, beginning in his late teens. This is the course of schizophrenic illness.”

The district attorney’s office declined comment for this story, citing the open case. Silver, Houston’s defense lawyer, says that she’s never seen a district attorney deviate from California’s standard practice of calling in two court-appointed physicians and seeking the additional evaluation of a third.

“I question whether he [Waner] believes in the insanity defense,” she says. “Some people don’t, even though it’s law.”

Ironically, the greatest doubt in the three doctors’ reports prior to Dr. Misset’s arises over whether Herczog’s symptoms are actually too perfect—in other words, whether he could be faking schizophrenia.

Dr. Broadman examined this most critically, quoting a jail psychiatrist who believed Houston might exaggerate and amplify his symptoms.

“He speaks in sophisticated language and seems to be logical much of the time,” she writes. “In my opinion, [he] has schizophrenia and experiences genuine delusions and hallucinations. However, he is intelligent and understands the hospital will offer him a better chance of treatment and relative comfort compared with prison. This would be a motive to exaggerate his symptoms. Even if he is exaggerating his symptoms, that does not mean he was not psychotic at the time of the offense. I believe he was.”

In the middle of her evaluation of Houston, hearing his explanation of why he’d killed his father, Broadman asked him if he felt an insanity plea was to his advantage.

According to her report, Houston’s reply was simple and brief: “I’m fucked either way.”

‘NOT CRYING FOR BLOOD’

Rallying behind Houston, the Herczog family feels misrepresented by a legal system acting on behalf of Mark. In a court case surrounding a brutal killing like Mark’s, his family might normally be the loudest voices demanding justice for the loved one.

“But we’re not crying for blood,” says Keys. “We’re crying for mercy.”

Mark’s sister adds that she believes if her brother had survived his attack, he wouldn’t have pressed charges. Her portrait of him is of a man lost, desperate—unsure what to do as he watched his son change. As he wrote on his calendar in November two years ago, he knew his son needed something. He just didn’t know what.

“All he wanted was to help his kid,” she says.