Walking into Phenotype, Annette Goodfriend’s new sculpture exhibition at Sonoma’s Alley Gallery, is like stepping into a natural history museum curated by Dr. Frankenstein.

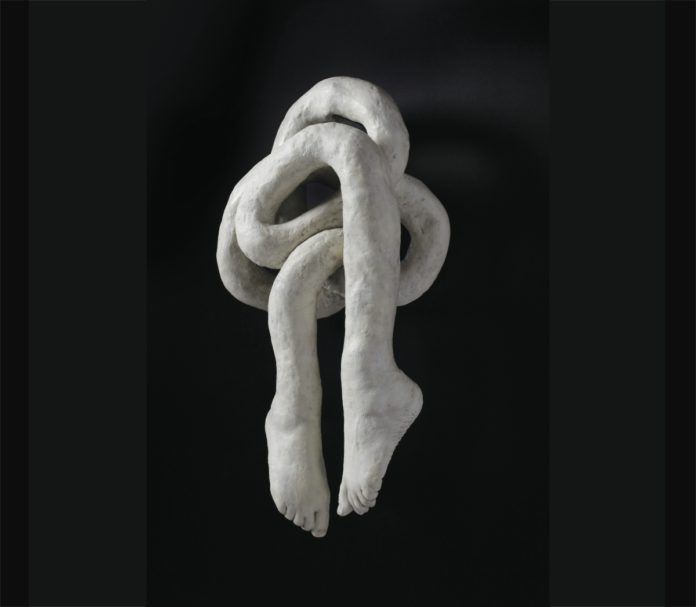

Rib cages bloom into unlikely appendages. Limbs seem to hesitate mid-evolution. Bodies appear assembled from plausible parts, yet refuse to resolve into anything anatomically correct. The notion of teratomas (tumors that sprout their own teeth, hair and nails) looms large. And yet, for all the Cronenberg-esque body horror, it’s beautiful.

Goodfriend’s work has long occupied the fertile overlap between art and science. The exhibition takes its name from the biological term describing the observable traits produced when genes encounter the environment. It’s the visible expression of invisible code. As Goodfriend explains, “The definition of phenotype is the visible characteristics that you see of an organism that result from its genetic makeup and environmental factors.” In other words, it’s not the blueprint but the outcome. And, if one is an artist like Goodfriend, a lot can happen along the way.

To be clear, her sculptures aren’t literal illustrations of genetic disorders or medical anomalies. They are speculative, surreal, even mordantly humorous (the knotted, noodly appendages leading to oddly expressive feet will draw a smile). Goodfriend describes the work as “looking at malfunctions in the genetic code that result in kind of perverse physical forms,” while emphasizing that the results are intentionally interpretive rather than diagnostic.

Materials play a crucial role in grounding that speculation. Working with steel and aluminum armatures layered with epoxy resin, rubber, plaster and wax, Goodfriend builds forms that are tactile and appear credible. The surfaces recall skin, cartilage, bone, and are expertly executed. The forms are convincing enough to persuade the eye of their verisimilitude, but not natural enough to reassure that something hasn’t gone terribly awry on a molecular level.

As she puts it, “I am telling a surreal story of biology. It is a visceral investigation of the perversity of nature, the role of science, and how our bodies both affect and are affected by the world around us.”

That phrasing—perversity of nature—captures the exhibition’s tone. In previous bodies of work, Goodfriend focused on the ocean and humanity’s impact on marine systems, examining environmental change from a global vantage point. Here, that same logic collapses inward. The site of consequence is the human body itself.

Perhaps tellingly, Goodfriend studied genetics at UC Berkeley while spending equal time in the art studio, eventually earning an MFA from California College of the Arts. The scientific curiosity never left; it simply found a more elastic medium. Now a full-time artist, she integrates cast body parts—sometimes her own, sometimes her son’s—with constructed forms, allowing her concepts to dictate material and method. “Whatever feels right for the piece,” she says, becomes the rule.

There’s a quiet narrative coherence to the show that benefits from being experienced as a whole. Solo exhibitions allow for that kind of sustained argument, and Goodfriend clearly values the opportunity.

“When you have a solo show,” she notes, “you’re able to put your different works in a single place, and it tells a story. … It kind of creates a narrative.”

In Phenotype, that narrative unfolds as a progression of altered anatomies—each one a different answer to the same underlying question: How does change manifest? Or, even more tantalizing: Why?

‘Phenotype’ is on view now through Jan. 25, with an artist conversation with Susanne Cockrell at 4pm, Jan. 17, Alley Gallery, 148 East Napa St., Sonoma. alley.gallery