In the North Bay’s agricultural community, Larry Peter is often presented as a hardworking and charitable dairyman who took a big risk by going into debt to purchase the Petaluma Creamery in 2004.

However, public records obtained by the Bohemian show that the story is more complicated. Over the past 20 years, Peter has racked up complaints with city, county and state regulators, and often failed to fix problems in a timely fashion.

Instead, Peter and his attorneys often cite his central role in the North Bay’s historic dairy industry and his business’s financial struggles as a reason regulators should go easy on him.

For a long time, Peter’s strategy seems to have worked well enough, but, as the Bohemian reported last month, Peter’s time running the historic Petaluma Creamery may be coming to an unceremonious end.

In a Dec. 21 letter to Peter, City Manager Peggy Flynn, citing the Creamery’s history of unpaid fines and uncompleted safety requirements, threatened to effectively shut down the business at the end of February if it does not complete a long list of safety improvements. Two months later, as the deadline nears, it appears Petaluma is sticking to its threat, despite Peter’s request for extensions.

In a Feb. 5 letter to Peter, Flynn stated that the city is still considering placing a lien on the Creamery to collect some of the business’s unpaid water use fees and fines, which city officials say total $1,425,258. On Friday, Feb. 19, Flynn told the Bohemian “we are working with the Creamery to gain compliance and that effort continues. There have been no extensions granted, and the February 28 deadline currently stands.”

The prospect of closing the historic Creamery, even temporarily, no doubt dismays members of the North Bay’s agricultural community. However, Peter’s track record begs the question: when do repeated code violations require a stronger response from regulators?

For instance, at the same time the Petaluma Creamery racked up fines and unpaid water bills in Petaluma, officials from the Sonoma County permitting and North Coast Water Quality Control Board attempted to get Peter’s Two Rock dairy to comply with environmental and building regulations.

And, although Peter and his attorneys routinely referenced the struggles of Peter’s businesses in conversations with regulators, public records show Peter has taken out loans to purchase numerous North Bay properties instead of paying off his decade-old debt to the city of Petaluma or bringing the Creamery into compliance with safety requirements.

Peter did not reply to a request for comment.

County Complaints

Over the past 20 years, Peter’s dairy business, located on Spring Hill Road in Southern Sonoma County’s dairy-heavy Two Rock area, was under scrutiny by Permit Sonoma, the county’s building code enforcement agency, for over a decade, and raised serious concern from a regional water regulator.

Between 2001 and 2004, inspectors with Permit Sonoma opened a series of investigations about the state of Peter’s property.

The range of alleged code violations included operating a creamery out of an unpermitted building, burying trash on the property, completing grading work without a permit and installing a handful of unpermitted buildings to house workers and host visitors on educational tours.

In a July 28, 2006 hearing with Permit Sonoma officials in front of an administrative law judge, Peter, who had recently purchased the Petaluma Creamery in downtown Petaluma, said he thought the structures were allowed by the property’s agricultural zoning or, in the case of the Creamery building, which he said was built in 1947 by a previous owner, were grandfathered into the property.

Peter told the judge he purchased the Creamery, in part, to comply with Permit Sonoma’s investigation. Now, he said, the Creamery was on the verge of bankruptcy.

The administrative judge ultimately ordered Peter to receive proper permits for some of the buildings identified by Permit Sonoma, to stop making cheese on the property, fix some other problems on the property and to pay fines for some of the unpermitted work discovered by inspectors.

But the case, which might have seemed close to complete, remained open for nearly a decade. After years of stops and starts, all of the necessary work was finally permitted and completed in October 2014. Then, all that remained was to come to a financial settlement, to cover Peter’s unpaid fines and cover the county’s expenses.

Eric Koenigshofer, an Occidental attorney and former West Sonoma County supervisor, represented Peter in his drawn-out fight with the county’s building permit agency.

On Dec. 8, 2015, Deputy County Counsel Holly Rickett responded, in frustration, to a May 2015 letter in which Koenigshofer laid out Peter’s defense.

“In sum Mr. Peter ‘argues’ that he is a good guy who provides important components to the Sonoma agricultural economy; that he did not rebuke the county and didn’t benefit financially from the delay; that he made some mistakes; and that ‘financial constraints’ kept him from coming into compliance sooner,” Rickett wrote.

Still, despite Rickett’s skepticism about whether Peter’s story would hold up in front of a jury, she told Koenigshofer that the county had agreed to knock down the fine considerably.

During the July 2006 hearing, a county permit official calculated Peter’s outstanding fines at $33,775, if Peter failed to file for the proper permits within 30 days.

By December 2015, Rickett said that the total bill had reached $83,717.88, due to daily non-compliance fines in addition to county lawyer’s fees.

But, instead of standing firm, Rickett told Koenigshofer that the county had agreed to drop a daily fine against Peter and cut the five years of county lawyers’ fees by 15 percent.

On Jan. 5, 2016, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors approved a $35,000 settlement with Peter for his permit violations, a meeting document shows. So, despite spending almost 10 years trying to get Peter’s property into compliance, the county settled for little more than it asked for in the 2006 hearing.

Koenigshofer did not reply to a request for comment about his work for Peter.

Waste Waters

But that wasn’t all. While county officials hounded Peter for building violations, the Sonoma County District Attorney’s office and state regulators pursued him for spilling nearly 50,000 gallons of wastewater into a streambed near his dairy property.

The saga began on Jan. 2, 2009, when state environmental regulators, responding to a tip, discovered dairy employees attempting to pump the manure waste water out of a stream bed down the hill from Peter’s Spring Hill Road dairy.

According to an account written by the state inspectors, dairy employees said the manure water spilled while they were trying to transfer it from one holding pond to another, days ahead of a projected rainstorm. Instead, the waste water spilled from the transfer pipe and down the hillside, where it began to form pools—some of them two-feet deep—in a dry stream bed nearly a mile from the sewage storage ponds on Peter’s dairy.

According to an account of the spill by a North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board (NCRWQCB) inspector, dairy employees hauled away 13 truckloads of the manure water on the afternoon of Jan. 2, for a total of 49,100 gallons of manure water. The dairy employees later used 35 truckloads of fresh water to wash the creek bed clean.

One of the neighbors told state regulators they first saw the spill on the afternoon of Dec. 31, two days before the state investigators arrived.

Two of Peter’s neighbors told inspectors at the time that manure spills were a common occurrence, though maybe not on the same scale.

“Manure water releases similar to this have been an ongoing problem, but agencies have not done anything about it,” one neighbor was quoted as saying.

In a July 2009 letter to the Sonoma County District Attorney’s office, Luis Rivera, then the acting assistant executive director of the NCRWQCB, recommended the District Attorney’s office press criminal charges against Peter for failing to notify regulators of his plans to move the wastewater, or of the spill once it happened, a violation of the state’s Water Code.

“Mr. Peter never filed a report of waste discharge prior to pumping out his pond, and allowing the waste water to flow to the creek,” Rivera wrote in his letter to county officials.

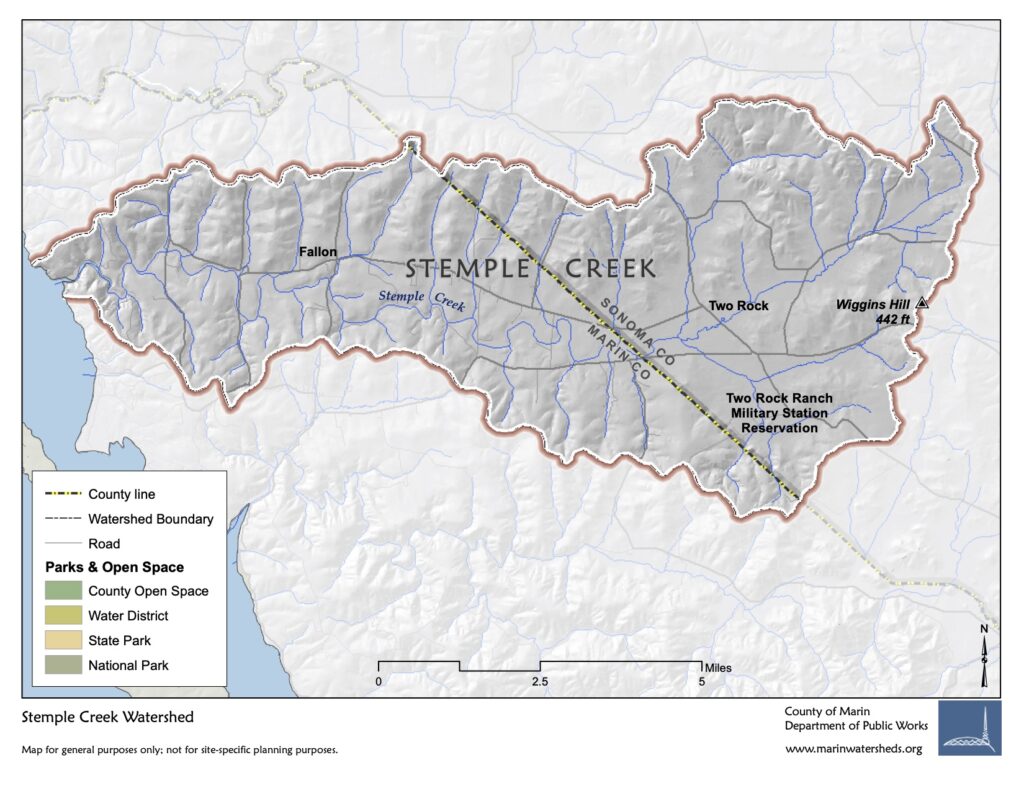

The spill was particularly notable because of the location of Peter’s dairy in the Stemple Creek watershed, a dairy-rich area surrounding a creek which bisects the Sonoma-Marin County border.

The watershed has been listed as “impaired” since 1990, a undesirable designation under the federal Clean Water Act, which indicates that a body of water has excessive levels of pollutants. In the case of Stemple Creek, it’s an excessive amount of nutrients and sediments in large part tied to the region’s heavy concentration of industrial agriculture operations.

A 1997 Water Board report states that the “Manure from concentrated animal feeding operations (dairies and poultry) has been identified as the primary source of the impaired water quality conditions in the Stemple Creek watershed.”

Sonoma County District Attorney Jill Ravitch’s office did not press criminal charges, but did pursue a civil case against Peter for unlawfully discharging wastewater.

On Feb. 14, 2012, Peter reached a court settlement with Ravitch’s office which required Peter to pay a small fine and to join the Water Board’s dairy waste regulation program, which, among other things, required him to file annual reports with the board.

However, Peter failed to follow the rules of the settlement.

In June 2014, Ravitch’s office took Peter to court again for failing to file his report with the Water Board two years in a row. In November 2014, the Water Board fined Peter $37,125 for failing to file reports properly.

Cherie Blatt, a water resource control engineer with the Water Board, told the Bohemian that Peter has paid the fine and filed annual reports properly since 2014. The Water Board has not received reports of a significant spill on the property since the 2009 incident, according to Blatt.

Purchases

Over the past six years, Peter has received press coverage for buying new businesses. The articles do not mention that he owed hundreds of thousands of dollars to Petaluma at the time of the purchases.

In July 2015, while Koenigshofer negotiated a settlement with Permit Sonoma, Peter purchased the Washoe House, a historic bar outside of Petaluma, according to press coverage from the time. Also in 2015, he purchased the Tomales Bakery in Marin County, Marin Magazine reported.

Property records reviewed by the Bohemian indicate that those purchases were part of a larger trend. In recent years, Peter took out large loans from banks, as well as smaller loans from members of some of Sonoma County’s older dairy families, to finance a string of property purchases.

In September 2018, for instance, Peter’s dairy property company, Western Dairy Properties, paid $3,900,000 for a property near his Spring Hill Road dairy.

On Nov. 20, 2020, Western Dairy Properties purchased a dairy farm on Peterson Road outside of Sebastopol for $2.1 million.

Peter has even continued to buy property after Petaluma ramped up its threats to close the Creamery in December. In January, Peter purchased two properties on Santa Rosa’s Mission Boulevard, according to public records.

Petaluma Cracks Down

In her Dec. 21 letter to Peter, after two small fires broke out at the Creamery in six months, Flynn, the Petaluma city manager, threatened to effectively shut down the business if it fails to meet a long list of safety improvements before the end of February.

Two follow-up letters sent by Flynn to Peter on Feb. 5 and Feb. 19 indicate the city is sticking to its threat to revoke the Creamery’s water-use permit and to decline to issue a crucial safety permit on March 1, despite Peter’s pleas for more time.

In a Feb. 5 letter, Flynn batted away Peter’s go-to argument: that his business is central to the region’s agribusiness and that its struggles to comply with regulations and pay fines are an inherent trait of the modern dairy business.

“We would like nothing better than to have the Creamery around for another 100 years—if it were operating responsibly,” Flynn wrote.

“While the dairy industry continues to struggle, the issue with the Creamery is not one of sustainability, but of accountability. Similar ag-supporting businesses in our community meet the rules and regulations, despite the challenges experienced in the industry. It is good, and necessary, for business,” Flynn added.

While it seems the city will stick to its threats this time, the crackdown has been a long time in coming—and, at least in part, pushed by an outside actor.

A February 2018 audit of the city’s wastewater pretreatment program obtained by the Bohemian states that members of the city’s Environmental Services staff outlined seven ways to increase the city’s enforcement efforts in a Jan. 5, 2016, letter to the city’s Director of Public Works and Utilities.

The recommendations ranged from requiring the Creamery to install additional monitoring equipment, temporarily shutting down the Creamery until it “demonstrates permit compliance” or immediately revoking the Creamery’s wastewater permit.

Although a city permit issued on Nov. 1, 2016 required the Creamery to install additional water bypass equipment, “none of the other recommendations in the memo have been implemented,” the 2018 audit, which was completed by a contractor to fulfill an Environmental Protection Agency requirement, states. As a result of the lack of action, the audit ordered the city to increase its enforcement efforts.

“The City is required to implement its [enforcement response plan] ERP by taking enforcement action to address Petaluma Creamery’s pattern of noncompliance and failure to comply with the bypass monitoring requirement of its permit,” the audit stated.

In April 2018, two months after receiving the audit, the city launched a legal action against the Creamery. And, in November 2018, a judge ruled that Peter owed the city $624,046.06 in 24 monthly installments. But, Peter did not pay the full amount by the Dec. 31, 2020 deadline, according to Jordan Green, a deputy city attorney.

Now, the city appears to be on the verge of closing the Creamery, at least temporarily, until Peter, or a new owner, brings it into compliance with safety regulations.