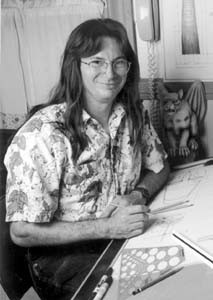

Dream Designer

Michael Amsler

David Prothero makes fantasy happen

By David Templeton

WARNING!” cautions David Prothero, as a guest steps unaware into his living room. “Warning! Here there be dragons.” Prothero is not being merely whimsical–though one could hardly look around the room and not be struck by the prevailing whimsy of the neo-gothic, gargoyles-and-ravens design scheme of the place. The dragons he warns of are real.

“Water dragons,” he explains, leaning over to scoop one of them up from its hiding place. Cradling the 2-foot-long, flushed-red reptile gently, he turns it about to gaze into its scaly face. “There’s another one around somewhere,” he says. “They’re pleasant little fellows. They eat baby mice.”

The gleefully macabre interior of Prothero’s Petaluma home is tempered by less off-beat–but equally playful–decorations: Numerous dwarves (the Disney kind) exist in various collectible forms, and sketches of Wizard of Oz landscapes hang on the walls. Prothero lives and works here, sharing the place with his two sons.

“This is fairly conservative for me,” he laughs. “I’m only renting. If I owned my own place I’d go a lot farther.

“I have a strong desire for a certain level of fantasy in my immediate surroundings,” Prothero adds. “It’s a natural environment in which to let ideas flow.”

It is ideas, after all, that are Prothero’s stock in trade. He is paid to have them, develop them, and put them down on paper. Occasionally some of these ideas are actually used, brought to life as underwater stage sets, whirling and rotating parade floats, labyrinthine theme-park rides, undulating chandeliers manipulated in time to soaring music, and gaseous clouds that form and re-form within the enormous lobby of a multimillion-dollar casino. All these miracles were made possible by ideas hatched right here in Mr. Prothero’s fun house.

Though others may have had the initial notion–be it a stage show, a traveling exhibit, or an amusement-park ride–it is to Prothero that those people come when they wish to make it happen. As the owner of Dwarf Productions–“A compact, efficient little company with big ideas” reads Dwarf’s letterhead–Prothero draws on his early schooling in theatrical arts and advanced physics to develop what he calls “interactive entertainment environments.” Part designer, part technician, he determines how each creative vision is going to be executed, employing a broad knowledge of available technologies and scientific possibility. Often, the end result is something that has never been accomplished or even attempted before.

“At the beginning of every project,” he says, flipping the pages of his mind-boggling portfolio, “you’ve got the high concept–that’s the initial idea, the creative element–on one side, and then on the other side you’ve got the reality: a client with a budget. I’m the guy who stitches the two together.”

Put another way, “I make other people’s stuff work.” He explains all this shyly, even humbly, pointing out that he started his career working backstage at the theater in his home town of Hibbing, Minn.

“Theater, particularly the backstage environment of theater, tends to attract all the square pegs that don’t fit in anywhere else. The anonymity of my work pretty much suits me,” he admits.

Among his many anonymous achievements–not counting numerous sets and special effects designed for his son’s elementary school plays and haunted houses–Prothero designed the stage and sets for “Splash,” the legendary Reno Hilton show that featured mermaids and mermen performing in pools and waterfalls among ever-shifting backgrounds. When the San Francisco 49ers won the 1984 Super Bowl, they celebrated their victory with a drive through the streets of San Francisco, seated comfortably on bleachers carried by a massive float of Prothero’s design, big enough to hold all the members of the team, along with their families.

Prothero developed the initial concepts of Walt Disney World’s innovative Disney Institute, designed major elements of Universal Studio’s popular Star Trek Adventure ride, and converted Vancouver’s PNE Coliseum hockey arena, with seating for 6,500 people, into a stunning Italian opera house for Teatro alla Scala of Milan’s production of Verdi’s I Lombardi during Expo ’86.

Most dazzling of all–literally–is one of Prothero’s most recent projects.

Called the Atrium Show, it’s “an architectural enhancement” of the walk through the atrium inside the Crown Casino Hotel in Melbourne, Australia. With fountains, lasers, lights, photographic projections, and audio effects, enhanced by mysterious liquid nitrogen fog and amazing floating cloud formations, the atrium–designed by an international team of artists and technicians, in which Prothero was a key player–has been transformed into a representation of the four seasons of the state of Victoria, animated and choreographed to a soaring orchestral score. Enormous chandeliers undulate overhead, change shape and color, and can be programmed to form patterns or star-fields in the artificial sky. The building itself, which cost a reported $2.5 billion, is the biggest casino in the world, and the largest building in the Southern Hemisphere.

“The Atrium Show was designed for people to walk through,” Prothero says proudly. “But they’re ending up with hundreds of people standing in one place as it unfolds in sequence around them.”

Still, for every Prothero project that has been realized, there are numerous others that never moved beyond the conceptual stage. This, he points out, is the way the business works.

“I get paid for the ideas, whether they are developed or not,” he shrugs. “What usually happens is that the client finally understands what he or she is getting into, how much money it will cost, and how much of their lives they’ll have to give up.

“Frankly,” he smiles, “it’s a lot easier if a idea never does get built. Because then we can avoid all the physical headaches. And in truth, most ideas end up becoming compromised in scope during that process. If it’s never built, it remains a pure idea.”

On the other hand, visiting Australia to oversee implementation of a billion-dollar wonderland is nothing to knock.

“That,” he admits, “was a fun little project.”

From the August 20-26, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.