Free Fall

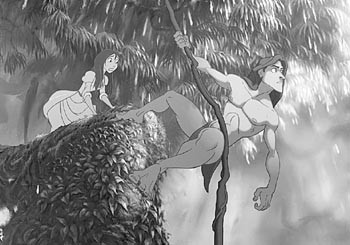

Out on a limb: How can a real-life acrobat compete with a cartoon Tarzan?

San Francisco acrobat Aden O’Shea takes a swing at Disney’s ‘Tarzan’

By David Templeton

Writer David Templeton takes interesting people to interesting movies in his ongoing quest for the ultimate post-film conversation. This column is not a review, but rather a free-wheeling discussion of popular culture.

ADEN O’SHEA is upside down. Dangling 30 feet above the floor, the 24-year-old acrobat, clad in blue tights and a fitted gray shirt, seems improbably at ease up there, in spite of his being wrapped up thickly in long coils of rope, head down, legs up, arms outstretched, while numerous folk, myself included, stare in disbelief.

Before returning to the earth, O’Shea will repeat this gravity-challenging maneuver several times, wrapping and unwrapping, climbing and swinging and pirouetting about like . . . well, like Tarzan. At last, having pulled the entire length of rope up to where he hangs, and having coiled it around his body like thread on a spool, he allows himself to unwind, slowly downward–all the way to the ground.

O’Shea–a circus performer since the age of 13 and one of the instructors here at the renowned San Francisco School of Circus Arts–stands panting as a class of young acrobats-in-training reward him with applause.

The 14-year-old school, which evolved from the Pickle Family Circus School and has been located, since ’91, in a cavernous old gymnasium across from Kezar Stadium, seemed a fitting place to meet after we’ve both seen Disney’s latest animated blockbuster, Tarzan, itself a marvel of acrobatic derring-do set against a lush jungle rendered in “deep canvas” animation.

O’Shea’s spontaneous demonstration of aerial craftsmanship has come at the end of our discussion, in which he admits being frustrated by the animators’ over-the-top depiction of the physical activities of Tarzan (given voice by Tony Goldwyn in the movie).

“Tarzan does acrobatics,” O’Shea says, sitting on the brightly painted bleachers overlooking the trapeze training area. “I do acrobatics. He works with ropes. I work with ropes. We both fly through the air. So I can identify with Tarzan, the mythic figure.

“But this Tarzan,” he says of the movie, “was less of an acrobat and more of an Extreme Sports type athlete. He was a surfer. A skateboarder. And most of what he did was physically impossible. It was the animator showing off.

“Frankly, I think the things that are possible–even just barely possible–are more exciting to watch that something that is not possible, even in animation. There are real people who can fly through the air, and the way they do it is thrilling.”

“I kind of thought [Tarzan] was thrilling,” I admit. “Sure, it wasn’t entirely realistic, but watching Tarzan zip through the trees made me want to be up there with him.”

“Well, me too,” O’Shea laughs. “And ‘zip’ is right. Tarzan hauls ass in this movie. He never stops. When he goes from limb to limb, from vine to vine, he’s so fast you can almost not get a sense of how he’s moving.

“Actually,” he adds, “I kind of got the sense that Disney was kind of uncomfortable with the idea of having this buff, nearly naked man in their movie, so they made him move so fast he could never be thought of as, you know, sexy.”

“He was still pretty buff,” I point out. “With all that momentum gained from flying so fast, you’d think his loincloth would have flapped up once or twice. What do you bet there’s some Disney animator with an outtake of a naked Tarzan pinned to his cubicle wall?”

But we digress.

“In spite of the fantasy elements,” I say, “the elation and freedom of flight does come through pretty clearly.”

“It does, and that’s good,” O’Shea admits.

ASKED TO DESCRIBE the sensation of learning to fly, trapeze-wise, O’Shea turns to face the elaborate rigging above us. Pointing out the bars from which the flyer and the catcher each hang, he says, “So you’re hanging there, and you’ve been practicing for months, and then finally you let go. You’re in the air, flying to the guy who’s gonna catch you. And just seconds before you were thinking, ‘This is too hard. What am I doing wrong? I’ll never be able to do this.’ And, ‘Shit! What am I doing up here?’

“But then you do it. You may not have done it perfectly, but you did it. This weightlessness has found you, for the first time ever–and time stops. There is no sound. In that moment you know yourself better than you ever have. Because now you know what you are capable of.”

Jeez. Trapeze as self-actualization therapy. Sign me up.

“It’s true,” he laughs. “It’s like therapy. You learn a lot about yourself up there. In fact, I think that’s the underlying reason for the fitness craze going on in America. People are discovering that when you feel yourself pumping iron, you are forcing a relationship with your own body.

“There have been renaissances of art and philosophy and science. There have been cultures of the word, and cultures of the painted picture. Currently, among the affluent of America, we are experiencing the culture of the body. From San Francisco, California to Texarkana, Texas, anyone who can afford a Stairmaster can be part of the culture, they can pursue the ideal of having a perfect body, a powerful body.”

“A Tarzan body?” I add.

“Of course. You know,” O’Shea says, eyeing the dangling ropes across the room, “I was sitting there during the movie, thinking, ‘Hmmm.’ As a performer, this Tarzan thing might be what the market will be asking for now.

“Maybe,” he grins, “it would behoove me to get comfortable working in a loincloth.”

From the July 8-14, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.