Reeding & riting: Among complaints of racism and copyright infringement, AI officials decried the terrible grammar of the school mag.

By Brett Ascarelli

Until recently, Robert Ovetz, Ph.D., held two jobs. He worked as an environmental advocate for the Sea Turtle Restoration Project in Marin and he taught environmental science, world conflict and cultural studies as an adjunct instructor at the Art Institute of California San Francisco (AI), a school for the commercial arts. His scholarship in sea turtles dovetailed with the school’s Eco Club, so he served as its faculty adviser for two years. During that time, he says that the Eco Club got new bike racks installed in front of the school, had the bookstore bring in a sandwich vendor where before there had been only vending machines and vastly expanded the school’s recycling program. In the spring of last year, the school gave him his second positive review and pay raise. But he says that in December, school officials told him that they wouldn’t return him to the classroom for the following quarter. Ovetz, 40, thinks he was fired because he criticized the school’s decision to censor a magazine, Mute/Off, that students in his cultural studies class published as an assignment last quarter.

Hoping to give students a broader perspective on media-making, Ovetz explains the magazine assignment by phone from his Mill Valley home. “The students could pick whatever topics they wanted, as long as they were related to cultural studies. I left everything up to them–how it would be designed, promoted and produced. I just played a role as the facilitator.” The assignment also required wide distribution of the magazine to the AI community.

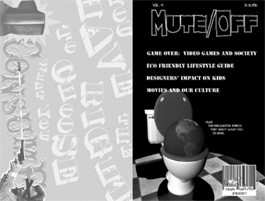

The students decided to write about film and society, video games, green living and the impact of consumerism on children and fashion. Toward the end of the quarter, they distributed some 500 copies of Mute/Off around the school. But the next day, Ovetz found only five copies of the magazine after searching the campus.

“The students were unanimous and thought the magazine had essentially been censored,” says Ovetz, adding someone had reportedly removed a copy of the magazine from the hands of a student who was in the middle of reading it. Ovetz claims that the school has a history of censoring student art, from a sculpture of an alien that one visitor claimed looked like a vagina to a sculpture of an African American breaking out of his chains. Ovetz also says that last quarter, a photo featuring toast with a milky substance and a condom was removed from the student exhibition “Taboos.” With reference to the sculptures, AI president Jim Campbell says he thinks they were simply cycled out of the student gallery after three months on display; he confirms that the toast photo was pulled.

After Ovetz discovered that Mute/Off copies were missing, he wrote an e-mail to the Dean of Academic Affairs, Caren Meghreblian, Ph.D., to find out if she knew anything about their disappearance. She responded to him that the school had chosen to remove the magazines “as a precautionary measure.” She cited potential copyright violations. (Mute/Off featured an Adbusters-style collage of corporate logos over which “Organized Crime” had been stamped.) The dean also wrote that one piece might be seen as “racially offensive.”

“[The dean] obviously didn’t read the article to the end,” says Ovetz, who thinks she was referring to a short story written by Simone Mitchell, an African American student in the class. Mitchell, 27, had been studying game art and design, and his story describes a group of three men who call each other “nigga,” steal cars, rape a woman and randomly shoot people. At the very end of the piece, the reader learns that the three gangsters are actually video game characters, played by three wealthy, suburban white kids.

Speaking by phone from his Daly City home, Mitchell says that a video game, Unreal Tournament 2004, that AI uses in its game design curriculum features “lots of people getting killed, blood everywhere and pretty much everything I described in my piece is right there. If you play it online, people make those sorts of [racist] comments all the time.”

Campbell says he hasn’t personally seen that game, but that review processes are ongoing at the school. Despite this, he notes, “We try to give our faculty academic freedom in the classroom and try not to censor their lesson plans or the materials that they use to deliver their lesson plans.”

In the student handbook, AI reserves the right not to display student work that may be objectionable. “There is a process to go through to be able to post work of any kind of the campus,” says Campbell. He says postings must reinforce what is being learned on campus–in other words, students and faculty can’t necessarily go around posting their personal work. He also says the review process is important, because sometimes work that might be appropriate for students may not be appropriate for younger audiences visiting the campus.

AI spokesperson Gigi Gallinger-Dennis explains, “In an effort to ensure compliance with AI processes and procedures, [Mute/Off] was removed from circulation, pending further review. And so to follow procedures, we collected the magazine, had it reviewed and then redistributed it after a full review by our legal counsel.”

Gallinger-Dennis says that the school will continue to review student work, but she says the school will make more information about the review process available this quarter so that students can “make sure they are in compliance.”

Does the First Amendment protect students from censorship?

Not according to Oakland’s First Amendment Project staff attorney David Greene. He says that private universities don’t have to uphold First Amendment rights, because they aren’t government actors. “Subsidized loans don’t make a private university a government actor,” adds Greene, who is also one of the lawyers representing Josh Wolf, the freelance journalist in jail for refusing to turn over his video footage of a 2005 street protest to the court.

However, censorship may violate the Leonard Law, a free speech law unique to California. “The Leonard Law prohibits a private, post-secondary school from disciplining a student [for exercising First Amendment rights],” says Greene. “The law doesn’t indicate whether the removal of a student publication would be discipline. I think it should be.”

Does AI see censorship as punishment? “No,” says James Campbell, “I guess we don’t. But we didn’t end up censoring the work anyway. I think we have the right to a review period.” He points out that despite some faculty who protested that Mute/Off was embarrassingly ungrammatical, AI still allowed it to be redistributed in its entirety.

Campbell also says that AI may start workshops for students and faculty to discuss what it means “to be an artist in today’s commercial world. With that freedom comes responsibility.” He points out that students who attend AI are going into “commercial-type environments, not fine arts.”

Once these students enter the professional world, Campbell says their work will be subject to review by the company they work for. “They need to understand the ramifications that go with their freedom of expression,” he says. “[These limitations are] not necessarily set by us, but by the commercial world at large.”

About a week after the magazine was picked up by the school, Ovetz says that the dean and the head of the liberal studies department declined to rehire him for the spring quarter. “They told me there was some issue of some conflicts with some other staff,” says Ovetz. “That was their reason. I find that to be disingenuous because of the two previous positive reviews and pay raises.”

As for Ovetz’s firing, AI will not discuss personnel matters, but the president assures that his firing had nothing to do with Mute/Off‘s content or circulation.

Ovetz has since won a James Madison Freedom of Information Award for speaking out.