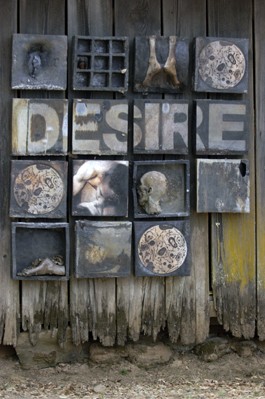

‘DESIRE’: The disparate clay pieces that Richard Carter brings together draw from his ‘Life After Life’ series as well as his own personal longings.

By Gretchen Giles

Like drawing, it is possible to see ceramics as a “mother” art, one that is necessary to claim proficiency in before moving on to exploring other media. At least, that appears to be the case at the Quicksilver Mine Co., which is currently exhibiting a show drawn from the workings of a ceramic studio, much of which has very little to do with clay.

Titled “Richard Carter Studio: Past and Present,” this collective exhibit showcases the work of some 20 students who have done residencies with sculptor Richard Carter. Formerly housed along the Napa River, Carter now oversees some 85 acres in the rural Pope Valley area near Angwin, running an in-house residency program centered on wood-fired kilns and community. Students may stay for extended, even open-ended periods of time during which Carter, a former French Laundry sous chef, finds them restaurant work in tony Napa eateries to help pay their artistic stipends, cooks for and with them, and helps them learn to live on his rural ranch.

Carter, 49, estimates that some 30 students have so far passed through his program, a strenuous life experience modeled after the teachings of his own mentor, Kansas City Art Institute instructor Ken Ferguson, as well as the Bauhaus-informed strictures of the late Pond Farm artist Marguerite Wildenhain. During their tenure, students live together, work collaboratively and, most importantly perhaps, tend the wood fires necessary to heat the Korean- and Japanese-style kilns that must burn ceaselessly for seven to 10 days at a time in order to get hot enough that they not only melt their own ash, they also puddle steel.

But to judge from the Quicksilver show, most of what emanates from Carter’s kilns is not adequate to make tea, serve tea or sip tea; few of the artists who train with him end as “functional” ceramicists, those who produce items for the table or hearth. Rather, those such as Brooklyn-based artist Paige Pedri have moved on to create, huge white corporeal figures, abstract and recognizable both, fashioned from burlap, plaster and wire that splay in reminiscence of Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox or the biomorphic hanging figures of Eva Hesse.

Needing to complete an apprenticeship under a mentor, German artist Kathinka Willinek came to Carter after finishing a rigorous study in functional ceramics in Berlin. After her time in Pope Valley, she went to Carter’s alma mater in Kansas City, but soon switched from the ceramic department to the sculpture department. The work she sent to Quicksilver consists of long filaments threaded through with short pieces of colored string that when looked at from a small distance reveal a quick sketch of a face and figure.

A current Los Angeles darling, sculptor Nathan Mabry came to Carter when he was still a high school student in Napa. Under Carter’s tutelage, Mabry also went to the Kansas City Art Institute, subsequently receiving his MFA from UCLA and his own show within the month. Mabry takes found objects and ready-mades and alters them with masks and other surprising additions as well as casting his own minimalist molds and models.

Guy Michael Davis, who shows slip-cast tree limbs and faux nests at Quicksilver, has founded a Midwest design firm; the singularly named Granite uses oil paint, garish cartoon figures and plenty of sequins to wreak satiric nudges; Jayson Taylor uses beading and white silk organza to reflect on God.

While many of the artists collected in the Quicksilver show did send functional pottery, as many did not. “I really question college ceramics departments,” Carter says crisply by phone from his Pope Valley ranch, “because if you’re making three-dimensional objects that aren’t functional, you need to be in the sculpture department; otherwise, you need a design education, and that is lacking in most ceramic programs.”

Ken Ferguson, Carter’s mentor, died four years ago after having made a laughable attempt at retirement in 1996, continuing on with KCAI as an emeritus professor and remaining a towering figure both on campus and on the national clay scene. With his passing, Carter also sees the efficacy of a ceramics program having passed, too. “Clay has always wanted to be accepted in the fine art world and it’s so stuck in its past and its function,” he says. “You end up with a teapot that’s trying to be a sculpture that’s not accepted by the fine art world and doesn’t function either. What’s being made is really reflective of what’s happening in that world.”

Carter’s own career is most hugely defined by a mammoth “Life After Life” series he completed in the late 1990s. Returning to the Bay Area from his education at KCAI, he was caught up in a sad swirl of AIDS and HIV-related deaths among his friends and contemporaries. He created a series of ceramic slabs studded with nails that he now says worked as a sort of emotional barrier, the nails a protective artifice. And then a friend stricken with AIDS came to him and asked to be an actual part of Carter’s work. “Troy came to me and asked me if I would cast his body because he wanted to be part of a piece that would help educate, he wanted to be immortalized,” Carter says simply. “He died 10 years later.”

The day after Troy’s death, Carter cast his body, creating a mold. He later filled the mold and recreated Troy’s person, eventually filling the vessel with Troy’s ashes so that it is both urn and testament. For years, Carter made work based on the memory of Troy Simon Burdine III, much of the work eponymously titled. “I did the whole grid series using pieces of his body, and it was compartmentalizing, it was the way that I was processing and then that became much less about him and more about me and my sexuality and fears,” Carter says with characteristic honesty.

After much self-reflection and striving, Carter finished with the series based on Troy’s body and moved back into his own emotional frame, gradually moving to the work he creates today, in which he wood-fires ceramic slabs studded with steel nails until the nails dissolve, informing the surface texture and color of the pieces. “I went back to that nail series [from college],” he says, “and fired those pieces so that they would melt. Now the barrier was gone and love came into my life. The barrier, the nails, were keeping me from what I wanted. It probably saved my life.”

Curiously, stepping back to old work has prompted a fresh vision. “These pieces are not as narrative as the ‘Life After Life’ series,” Carter reflects, “they’re not as content-driven. For me, what I walk away with is what’s most important. Rothko could paint a canvas just red or black and evoke feelings and emotions. It all connects to the feelings. This is a relatively new series, but for me it feels very current, because I think that art and craft need to reflect the time in society that it’s made.”

Having spoken with a very eloquent frankness about his work and his emotional life, Carter sighs. “I hate giving interviews,” he says. “I express myself so much better in clay.”

‘Richard Carter Studio: Past and Present’ continues at the Quicksilver Mine Co. through Dec. 7. 6671 Front St., Forestville. Open Thursday–Monday, 11am to 6pm. 707.887.0799.

Museums and gallery notes.

Reviews of new book releases.

Reviews and previews of new plays, operas and symphony performances.

Reviews and previews of new dance performances and events.