Sculptor Richard Shaw says that he has found a way to avoid the anxiety of the blank canvas. Rather than depicting something that might never have been seen before, he makes a teapot. Rather than conjuring a fantasy figure straight out of nowhere, he makes a bowl. Rather than calling up some imaginary creature never before known to humankind, he makes a vessel. But the forms that his teapots, bowls and vessels take are not previously known to mankind and can’t dispense tea, hold oranges or suffer flower arrangements. Shaped like bowler hats, demitasse cups, cookies, walnuts, cakes, playing cards, cheese wedges, lemon slices and other homely domestic nouns, Shaw’s ingenious porcelain pieces intend to trick the eye and lead the mind.

“If you make it functional, you have to jump through a lot of hoops, make a lot of decisions about it,” Shaw, 69, explains by phone from his Fairfax home. “It’s not making fun of functionality, it’s not not respecting it, but respecting it and making fun of it at the same time. Just because something’s a painting doesn’t mean it’s art; just because it’s a teapot doesn’t mean it’s not art.”

Shaw’s circuitous phrase “it’s not not respecting it” gives a hint at the method this UC Berkeley ceramics professor takes to arrive at his work and his method. Trained at UC Davis and the San Francisco Art Institute, Shaw is internationally known for his trompe l’oeil technique in slip-casting porcelain so that it uncannily resembles its inspiration, be that a cigar or a novel. Mentored by Cotati sculptor Bob Hudson, his former teacher and merry collaborator, Shaw is among that group of Bay Area artists who very much dislike being described as “funk” artists—and yet inevitably are—including Woodacre’s painting punster William T. Wiley, di Rosa Preserve stalwart Viola Frey and the late Robert Arneson.

The Sonoma County Museum honors his career with “Richard Shaw: Four Decades of Ceramics,” a 40-year retrospective of his work opening Jan. 29.

Shaw, who intended to be a painter, arrived at art school just as ceramic work was changing from earnest functionality to freer sculpture. Writing in the museum’s companion catalogue to the show, Sonoma State University art history professor Michael Schwager notes, “It was a time for breaking rules, and Shaw was ready to do so technically, structurally and aesthetically in clay.”

His first pieces worked and reworked a sinking ship, an image he had obsessively drawn in high school, having been forced to read a Reader’s Digest version of the Titanic tragedy for several consecutive semesters. But Shaw sunk his Titanic into a couch.

At a wedding, he thought it would be funny to remove the bride and groom statuettes from the cake (he was nearly alone in thinking so), and that disaster of manners led to him casting his own wedding figures. And so on, with life presenting all manner of opportunity for Shaw to lampoon, examine, mimic and transform.

In the early 1970s, when he and Robert Hudson were neighbors in Stinson Beach, the two began to collaborate, using the same materials—mostly domestic cast-offs culled from area thrift stores—the same paint and the same molds. Neither worked on the other’s sculpture, but all materials and inspirations were shared. What had been intended to be a summer’s lark turned into two intense years of immersion that helped Shaw hone the ingenious trompe l’oeil technique of which he is the undisputed master.

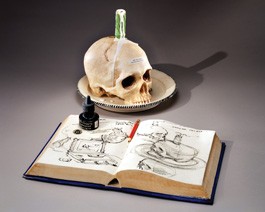

But critics and art professionals are quick to remind that there’s much more to Shaw’s work than meets—or tricks—the eye. A recurring motif is that of the cup with a plate, perhaps a cookie and a book. “I think that if you look at the titles of the books, there are so many levels where he’s being very subtly creative and sometimes not so subtle and is joking,” says Sonoma County Museum executive director Diane Evans, who curated the show. “The little bits of debris on the plates. One thing that people tend to overlook with his work is the blue and white work—look at the artwork on the plate, he’s created all of the designs and patterns, playing upon traditional Asian designs. None of these are direct copies from some object in nature. He manipulates everything.”

The “blue and white work” that Evans references is Shaw’s homage to the traditional Blue Willow china pattern prized by the Victorians and ubiquitous now. Looking closely at the familiar dishware, one can see that Shaw has entirely redrawn the figures. “As a kid I didn’t like it, but I liked that it told a story,” he explains.

Ah, the story. Narrative is rampant and intended in Shaw’s work, and he gives lots of intriguing clues for viewers to mull over. “The realism and the transition of the materials grab people, but hopefully there are layers going on,” he says. “It’s about people looking at things that they probably wouldn’t spend that much time looking at otherwise, like junk, and the story of why that is put together, because a lot of times I’m trying to pretend I’m someone else. Especially in the still lifes. You can read it: Is it a male who did this, or a female? What were they drinking when they left that coffee cup? What kind of book were they reading? That’s the narrative and then just enjoying the works for what they are.”

Michael Schwager adds, “The wow factor that everyone, understandably, has when seeing Richard’s work is that it is technically such a tour de force. He has such prodigious skill. But people who give thought to artwork at all talk about the content, the storytelling and the implied narrative that’s there, as, actually, does Richard. This little tableaux he creates—there’s a cigar sitting on the edge of a tray of watercolors or a house of cards—the story part is what grabs people and holds people and that’s what given Richard a sustained career. However, his renown and respect in the field would be less if that were all that was to it.”

Long married to the painter Martha Shaw, who is being given an adjacent exhibit of her solo work at the museum, Shaw is known for regularly biking from Fairfax to his Berkeley teaching post and for playing bluegrass guitar and soccer. What some may not know is that under this athletic family man there lurks the heart of a romantic—specifically, one whose romance is with materials.

Shaw’s sculpture often juxtaposes an artist’s palette or watercolor box or sketch book with other items. He explains: “There are a lot of materials that have so much possibility, like if you buy the right kind of brush, it will make everything turn out all right. With a palette or the watercolor boxes, it’s not what they make but what is used to make it. I think there’s a real romance in art and art materials and traditional materials.”

Forty years is long enough to get good at something. The challenge is in keeping it fresh. “I take chances once in a while,” Shaw explains. “Selling isn’t the priority, but you can tell that when people buy things, it’s because it moves them some way. In every show, there’s some work that goes in a new direction and that kind of keeps me alive.

“If I can do what I’m known for and find a way to make it interesting to me,” he laughs, “all the better.”

‘Richard Shaw: Forty Years of Ceramics’ runs Jan. 30&–May 30 at the Sonoma County Museum. A public reception is slated for Friday, Jan. 29, from 5pm to 7pm. 425 Seventh St., Santa Rosa. 707.579.1500.

Museums and gallery notes.

Reviews of new book releases.

Reviews and previews of new plays, operas and symphony performances.

Reviews and previews of new dance performances and events.