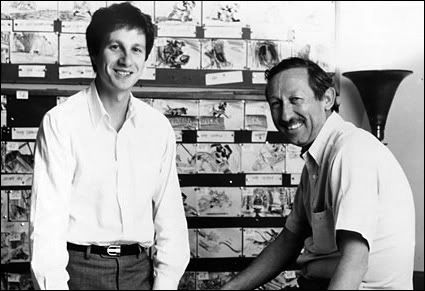

Peter Schneider, left, with Roy Disney. When did you start at Disney?

Peter Schneider, left, with Roy Disney. When did you start at Disney?

I started in 1985. I got there just after The Black Cauldron was released.And trounced at the box office by The Care Bears Movie.

Yeah, that’s correct!What was the atmosphere when you came on? Was it a depressed environment?

When Roy Disney engineered the takeover, and brought in Frank Wells and Michael Eisner, there was no real support for animation. And there was a feeling it was going to be closed down. Without Roy, it would have been—Michael Eisner disagrees with me every time we talk about it, but never mind that. There was a sense that it was not important. All the animators had been moved off the lot, out of the very fancy building it had been in for years, and into warehouses in Glendale. So everybody was both depressed, and free, and ready to prove themselves but didn’t know how. We have a great scene in the movie where they feel it’s the end of Disney animation, and they re-stage Apocalypse Now. We have it on film; somebody taped it. And it’s one of those great moments, where you realize these are nutty, wonderful, fabulous people. And I think they truly felt their job was over.So there’s a little bit of we’ve-got-nothing-left-to-lose, and a little bit of let’s-be-as-rabidly-creative-as-we-can.

I think that’s correct. And I think that’s why it all happened. For me, it all happened because this extraordinary group of people got together and said, ‘Let’s do it.’Historically, those who work on Disney movies don’t get credited. With this documentary, did you want to put a human face on the animators?

I wanted to put a human face not just on the animators, but on the crew of people that worked at Disney—people like Jeffrey Katzenberg, Roy Disney, Michael Eisner. And the artists. It was an extraordinary period of time, as you well know. The Disney company is extraordinary as it is. But an extraordinary group of people came together, and did something quite wonderful. Our goal was to capture that in a way that’s never been captured before.You certainly got a lot of exclusive footage. No one else would have been able to make this film.

I think you’re right. I mean, we had a really good time doing it.Of the stable of animators from that era, one of them’s John Lasseter. What do we get from him in this film?

John, of course, was there at the beginning of the process. And then he left. And then he came back when we did Toy Story together. What’s extraordinary is there’s a home movie in this movie, of Randy Cartwright, shot walking around the studio with a Super 8 camera. And the cameraman happened to be John Lasseter. So we have John Lasseter throughout the whole thing, in some sense.Cameras were not allowed on the lot, I presume?

That’s right. It was all forbidden footage.After putting it in your film, was Disney angry with the footage?

No, no. Disney was extremely supportive of what we did. I mean, I would love to say that gosh, no they weren’t supportive. But they really, really were champions with us. They gave us a lot of resources and access. I would say that Jeffrey, Michael and Roy—the three principal players—were all extremely generous with their time. And I’m so glad Roy saw it before he died. We got the last interviews with Roy. That’s the exciting part for me; that we got the support, and that everybody felt we’d portrayed the situation honestly and forthrightly. I think they were all extremely pleased by it.It seems like this documentary could have been a lot nastier. What made you keep it civil?

Well, for me, being there, there were no good guys or bad guys. There were no villains in our piece. This really was an opportunity to find the joy—and the frustration, and human foibles in all of us—in the process of what we did. I would say there was no reason to be nasty. No one set out to be a villain. There are no villains. You know what I mean?From that era, some of the greatest songs are from The Little Mermaid. Tell me a little about Howard Ashman.

I think Howard was one of the central and key figures that transformed this period of time. He was… as Roy Disney says, ‘I don’t want to compare him to Walt Disney,’ but he certainly had that same feeling, When I examine Roy’s statement, what Walt was was an extraordinary storyteller. His ability to communicate an idea, to inspire people, to make their ideas better. Howard had all those characters of Walt’s. He wasn’t just a lyricist, he wasn’t just a song guy. He was a storyteller, fundamentally. Howard prematurely died from AIDS, as we were finishing Beauty and the Beast, and I think it’s a huge loss. Beauty and the Beast and The Little Mermaid are some of the best works that he ever did in his life.With Howard Ashman gone, with other key people like John Lasseter and Tim Burton gone, do you think the Disney company can ever replicate the spirit or the success of this second golden era?

Certainly there are great movies coming out. But I think there was a specialness about animation back then that was unique, and caught the audience by surprise. Animated movies, as you said, were relegated to the Care Bears, way back then. Here we had a group of people coming together who changed the face of animation. And now animation’s just a darn good part of the movie business.It’s a huge part of the movie business.

A huge part! It’s no longer special. It doesn’t mean it’s bad—in fact, it’s pretty damn good. But it no longer is that special, oh-my-God. Of course you go to animated movies. I can’t wait to see Shrek Forever After and Toy Story 3 and How to Train Your Dragon and Dumbo 7 or whatever else is coming out this summer.When you say it’s no longer special, is that at all due to the influence of computer technology?

No. Because what we want in moviemaking, whether it’s live action or animation, we want to be taken someplace we’ve never been to before. To worlds we never imagined. To stories that are beyond our emotional scope. No one thought animation could do that. And then along came Howard Ashman, John Lasseter, etc., and they took you to places you’d never been before, and you felt it was real. Now, with the advance of computers, and with people understanding the value of it—Avatar, Alice, etc.—the line between what’s animated and live action are blurred. And animation no longer is one company with one group of artists. It’s an industry-wide phenomenon, where people are doing darn good work, but which makes it less special.Do you ever finding yourself tracing the current animation explosion to The Black Caulron, and The Care Bears, and the animators getting kicked out of their building? If that hadn’t happened, maybe The Little Mermaid wouldn’t have been made, and maybe animation wouldn’t be as huge an industry as it is today?

I have to think you’re right. And I think that’s what the documentary tries to explore, which is all these factors that serendipitously came together—there was no design, or plan—it just was over a period of time, these things came together.When did you leave Disney?

I left in 2001. I’d been there for 18 years, it was time to do something different, and the company was changing. But I left on great terms. My goal was to leave and have lunch and dinner with Michael, and to continue to fly on Roy’s plane. And I’ve done all those things. So it’s been great.Peter Schneider appears for a Q&A after the 4:30 and 7pm screenings of Waking Sleeping Beauty on Thursday, May 20, at Rialto Cinemas Lakeside. 551 Summerfield Road, Santa Rosa. 707.525.4840.