One shouldn’t expect calm still-lifes or landscapes in Hamlet Mateo’s latest work at Healdsburg’s Hammerfriar Gallery, which opens a seventh-anniversary exhibit on Feb. 11 running through April 7. Influenced by bawdy 17th-century English broadsheets, the multimedia artist’s work steers toward the tumultuous, provocative and even sinister.

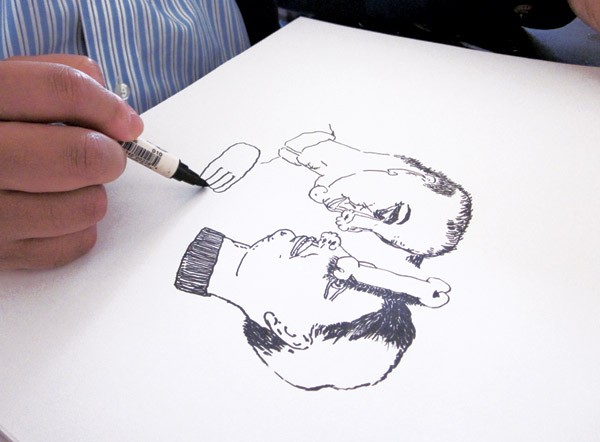

In the living room of his Graton home, holding his teacup Chihuahua, Doris, in one hand, Mateo flips through the pen-and-ink drawings that make up his new series, “Early Man.”

“I became obsessed with drawing these little figures that were holding a little document in their hands—it was very elaborate, almost royal-looking,” says Mateo. “They’d bring the document to all of these places, where there were natives that they thought were culturally and spiritually inferior. They’d tell the natives, ‘We are in charge now.'”

The series tells the story of colonialism, opening with depictions of stiff military-jacketed colonialists standing before a flowered background. The drawings grow progressively wild, morphing into orgies of animals, naked “natives,” writhing colonialists and shadowy humanoids whispering nefariously into the ears of Mateo’s half-men, half-ape creatures.

Mateo, 38, says he was driven to create the pieces after becoming immersed in studies of cavemen and early human culture.

“I have an imaginary country called Mongo,” he explains. “I started to think, here are these people coming in their big boats, and they’re taking over certain parts of Mongo. What are they thinking? How can they more or less justify the type of erasure that will take place once they get there?”

Originally from the Dominican Republic, Mateo and his family immigrated to the Bronx in 1987. He swiftly experienced harassment, racism and homophobia, he says—not just from other kids, but from his own family members—which informs his work to this day. In addition to pen-and-ink drawings, Mateo creates zines, live performance pieces, conceptual installations and short films, and remains interested in subverting narratives and creating environments that challenge what is and what isn’t real.

“I create a narrative that’s completely untrustworthy,” Mateo says. “I create these types of environments where you’re not ever really sure if the text is a joke or if it’s real.”

Mateo credits Hammerfriar founder Jill Plamann for consistently being open to work that is more provocative than her contemporaries. “Often, my experience is that there are drawings and types of art that I want to do,” he says, “and that I haven’t been able to do in other places because they were too strange.”

The anniversary exhibition also features “Wood Grains,” a series of paintings by Mary Jarvis, and “A Narrative of Elements,” sculpture by Luke Damiani.

“My vision deals with time, space, humanity, philosophy,” says Plamann on the phone from her gallery. “I have a horribly strong passion for educating people in Sonoma County about art.”

Plamann wears a visionary zeal for conceptual art. She’s purchased several pieces by Mateo, and speaks enthusiastically about bringing him into the “museum arena,” to places like SFMOMA. And looking ahead, Plamann’s energy is boundless.

“We’re moving fast here,” she says. “I’m on the outlook for good, conceptual artists around the North Bay. I have so much space. I need to fill and I want to grow.”