“But they choose to come here.”

It’s a common argument one hears in the ongoing debate about immigration—that because immigrants choose to come to the United States, they deserve to deal with the results of that choice.

But what if they didn’t have a choice?

The Immigration Policy Center estimates that there are 1.4 million immigrants currently under the age of 30 who were brought to the United States before the age of 16; have lived continuously in the country for at least five years; have not been convicted of a felony, a “significant” misdemeanor or three other misdemeanors; and are currently in school, graduated from high school, have earned a GED or have served in the military.

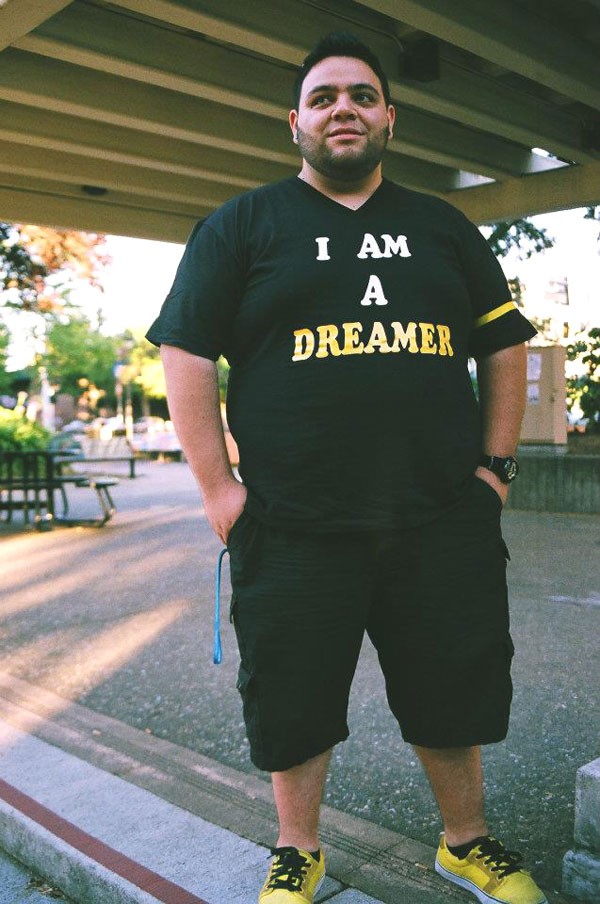

These are the “DREAMers”—young immigrants named for the DREAM Act who were brought here as minors and who dream of one day becoming U.S. citizens. Often, DREAMers go unnoticed. Many do their best to keep their undocumented status secret for fear of being deported. Many have lived and worked in their community so long that their citizenship isn’t questioned. And although some were brought to the United States as young as one month old, they have no way of applying for citizenship here.

After the DREAM Act failed to pass the Senate, Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano announced President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in June, 2012. The program prevents DREAMers from being deported and allows them a work permit and, in some cases, a driver’s license. The catch? An application for Deferred Action costs $465, requires a massive amount of paperwork, takes roughly eight months or longer to be processed, and, if approved, expires after two years. While the program does help DREAMers buy time while Congress continues to debate Comprehensive Immigration Reform, it does not alter one’s immigration status, nor does it provide a path to citizenship.

There are untold numbers of immigrant youth in Sonoma County who keep silent about their families. But because of Deferred Action, and due to “Coming Out” advocacy efforts nationwide, more and more DREAMers are breaking that silence. Here are some of their stories.

Xisamena, a 19-year-old Santa Rosa Junior College student, has always known she was undocumented, but she felt it the hardest after turning 16. While others were taking driver’s ed and applying for jobs, she says she realized, “Oh—I can’t get that.”

Xisamena arrived in the United States at the age of three, and she quickly adapted to American culture. Although Xisamena wasn’t born in the United States, she says, “I feel like I’m legal, even though I know I’m not.” She’s proud of her roots and what her struggles have taught her, but, she says, “I don’t remember anything about Mexico. I should say I’m Mexican, but what is my true culture?”

It’s not easy for Xisamena to tell others about her story. One of the first times she did was during a school assignment that required her to write her own constitution. In it, she gave herself freedom from her legal status by assigning herself and her family Social Security numbers. When she turned her project in, she had a moment of remorse. “I didn’t know what to do, I was in shock that I basically just told [my teacher], ‘Yeah, I’m illegal.'” Though no harm came from it, Xisamena didn’t feel safe sharing again—until now. “It’s taken me a long time to accept it,” she says.

[page]

Both Xisamena and her brother applied for Deferred Action in August. They have yet to hear back. She attended three different application workshops, but decided to seek help from a private law office after she found some errors while looking over her initial applications. Private help wasn’t cheap, but Xisamena and her family didn’t want to take the chance of filling out the application incorrectly. “One mistake and it’s rejected. The lawyer wanted $500 for helping me fill it out,” Xisamena says, “but his secretary told me she would help me for $200.”

Xisamena hopes that once she gets her paperwork, she can finally have a sense of security; right now, she has a one-hour commute to attend college, and she worries about being pulled over every time she gets into her car. But another thing she looks forward to is traveling. Although Deferred Action won’t grant Xisamena her lifelong dream of going abroad, she wants to spend her two years of Deferred status exploring the United States—the only country she’s ever remembered calling home.

When Jorge was six, his mother discovered that his father had a separate family in a different town. His father left shortly after. “In Mexico, there is no child support,” Jorge explains. “We all had to live in one small room because my mom became a single mom.”

After years of suffering and instability, Jorge’s mother left him and his sister with an aunt in Mexico so she could come to America to provide a better life for her children. While crossing the border, she was stripped of her clothes and robbed by the man she paid to help her cross. Eventually, after about a year of working as a janitor, Jorge’s mother had finally saved enough money to come back for him and his sister. In her absence, Jorge became angry without any parents to provide guidance, and he remembers missing her so much that when she came back, “it felt like Christmas when you wake up and find your toys.”

When Jorge was 14, his family journeyed across the desert on a blazing hot day for what he considers the most physically demanding walk of his life. Although the walk was long and hard—and resulted in horrible sunburn—the night was worse. “Regardless of how hot it is,” he says, “you have to bring a jacket, because at night, you’re freezing.”

Jorge’s mother paid $3,000 per person in order to be led though the desert, and now, Jorge says, “I hear it’s even more.” As he was walking across the hot desert with the sun burning down on him, he remembers being warned by his mother not to trust anyone after her first crossing experience, and thinking, “I’m 14 years old. They can overtake me and my family.”

It was two years before Jorge realized that what he did that day wasn’t legal. At the time, he was very involved in his school’s book club, and together with his classmates, helped fundraise for a class trip to Italy. Once it came time to prepare for the trip, Jorge was asked to bring in his passport, but when he asked his mom, he didn’t get the answer he was hoping for. “My mom was just like, ‘Mijo, you can’t. You don’t have papers,'” he says. “That’s when I knew this was going to suck.”

Since, Jorge has realized there’s a lot more he can’t do. After he graduated, he went to his school counselor for help applying to college. He dreamed of going to a UC but would have needed financial aid, and as an undocumented student, Jorge was ineligible, even though he had good grades. The counselor told him it would be a waste of time to apply. “I was completely devastated,” he says, “but she was right.”

Through all of this, the scariest moment in Jorge’s life was when he was pulled over by a sheriff in Rohnert Park and taken into custody for driving without a license. He was then told that immigration enforcement would arrive at the jail at 6pm. From there, Jorge became emotionally destroyed. He used his one phone call to contact a bail bond agency, but the woman on the other end told him, “I’m sorry, we’ve been having a lot of these calls and we can’t do anything, even with a signer.”

While in jail, Jorge kept thinking, “I’m not a criminal, and I work hard at shitty jobs, never take anything from anyone, that’s how I was raised.” Luckily for Jorge, someone took notice. He had made plans with a friend, and when Jorge didn’t show, his friend knew it was unlike him. He got worried and called the hospitals and, finally, the jail.

[page]

By the time a police officer came to tell him that his friend had posted bail, Jorge was numb. “My name gets called at five, and I’m watching the clock,” he remembers, with relief. “My eyes were dry—I didn’t have tears anymore.”

Jose—or “Pillo,” as he prefers to be called—arrived in the United States with his mother and sister at the age of 12. His family entered with a visa, but after two years, when the visa expired, Pillo stayed. From then on, he began life as an undocumented student.

Now in his 20s, Pillo has had to adjust to life after Deferred Action. He’s still not used to the perks. Sometimes he forgets that he can wave at police officers instead of avoiding eye contact. After receiving his driver’s license, he was pulled over around the corner from his house. When the officer asked for his license and registration, out of habit, Pillo replied that he didn’t have one. “When he repeated, ‘You don’t have one?’ I remembered, ‘Wait a minute, I do.'”

Although Pillo is thankful for what Deferred Action has given him, he adds, “Its only temporary, it doesn’t fix anything. Who knows? Two years from now, I could be back in limbo.”

As of now, Pillo’s main concern is to push for broader change. “They won’t hear one, but they’ll hear millions,” he says. Pillo is a member of the DREAM Alliance of Sonoma County, an organization dedicated to helping pass immigration reform. “We’re not going to stop until it happens,” he says.

Although Pillo has shared his story in Washington, D.C., it wasn’t easy for Pillo to “come out” as an undocumented student. The first time he did, he was in a political science class at Santa Rosa Junior college. Pillo had been the quiet kid in the back of the classroom who didn’t say much until one day, his class watched a film on immigration. The teacher asked for opinions from the class, and a girl in the front row went “off about how the illegals were taking all the scholarships,” he says.

After sitting though her speech, Pillo had enough. He got up in front of the class and said, “Undocumented students don’t get any financial aid, everything is out-of-pocket. I’m not telling you from someone’s friend or someone’s cousin—I’m telling you from personal experience.” The girl was so ashamed she grabbed her stuff and walked out, and according to Pillo, the mentality of the class changed from that moment on.

Pillo doesn’t always get positive reactions. A girl he had been friends with through high school once said she was disappointed in him for being “one of those people that she always hated.” And Pillo knows there are many young Latinos struggling with the same problems he did.

“That’s why I speak,” he says. “Yes, it’s rough, but I want people to know there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

At his job and in his volunteer work, Rafael talks to hundreds of DREAMers every month, and sees firsthand the way their fear and their families’ fear is exploited. “There are individuals that are taking advantage of other individuals, and it’s all about making money,” he says.

Rafael is head of the Extended Opportunity Programs and Services department at Santa Rosa Junior College. He devotes most of his time to helping DREAMers find scholarships and financial aid, and, since the announcement of Deferred Action, has spent many unpaid hours helping hundreds of others apply. One of the youngest he helped was two months old when she came to the United States. “She has saluted the flag since she could,” says Rafael, “and yet now her fate in this country is one day here, maybe the next she’s gone.”

Rafael has seen plenty of desperate families willing to pay hundreds and even thousands of dollars to have their applications for Deferred Action filled out by attorneys or other “experts” because they’re afraid of having their paperwork rejected. Hearing of these scams has motivated him and his team to hold three-hour application workshops; in an economy where many families are struggling, taking advantage of hopeful applicants is unjust, he says. Most have had to work more than one job in order to pay for school.

Although Rafael does his best to warn DREAMers of scammers, he also tries to let them know that there is help out there. He says that for every con artist, there will also be churches and government officials “who just come together to provide a service that needs to happen. And I think that that’s what makes this country great from that point of view—that when there is a need, people come together and they help each other.”

While the program has brought some people together, it has also caused sibling rivalry, Rafael says. “We are already seeing a little bit of conflict between younger siblings who say, ‘Why does she qualify, but I don’t?'” Not that this is new to him; Rafael has also seen many families where only some family members are American citizens. “It’s common where you bring children who are seven or eight years of age,” he explains, “and as soon as you get here you settle down and you end up having another child or two children.”

What Rafael finds the most interesting is the fact that the immigrant child tends to be more successful than the one who is a citizen. “When you realize that you’re undocumented,” he says, “you see the need to work harder.” Not all families are divided by citizenship status, however. In some households, Rafael has seen older siblings who aren’t eligible for Deferred Action willing to work extra to pay for a younger sibling who qualifies.

Although Deferred Action doesn’t offer as much as Rafael would like, he notes how it’s brought people together. “Being undocumented is a solitude situation,” he says. “You don’t tell your friends, you don’t tell your enemies, you don’t tell anybody, really. It’s a very private, stressful, emotional situation.” As a result of his workshops, up to 80 people have been able to look around the room to see others in the same situation. “It is amazing to see that level of unity; where you get to see your neighbor, and this is the first time that you notice your neighbor is also undocumented.”

Rafael hopes that what he’s noticed as a change in attitude about immigration will continue. The younger generation, in particular, is more accepting of DREAMers. “They know that a lot of their friends are undocumented,” he says, “and if [ICE] was to come over and try to take their friend away, they would do whatever was necessary to prevent that from happening.”

He credits this new attitude to the young DREAMers who have spoken up and fought for this change.

“It was the youth who wrote in Time magazine,” he says, “it was the youth who have all those videos on YouTube where the students are telling their stories. They started this movement.”