Pat McPherson rattles off facts about his town water system as easily as some people cite baseball stats. He knows that two companies—one public, one private—maintain pipes and treat water in his inland Southern California community. He knows where the border lies.

“You could live in the city of Ojai, and on one side of the street your water bill is $150 and on the other side it’s $650,” he says.

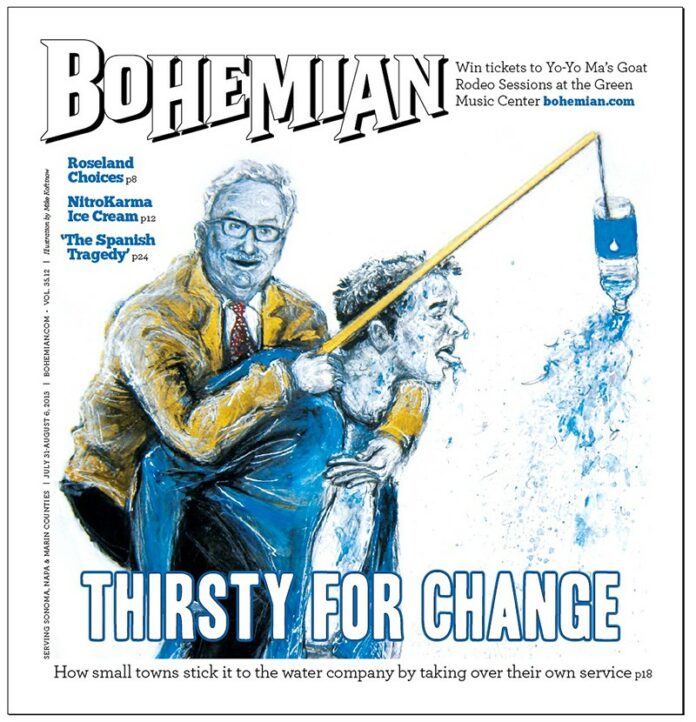

The private company issuing the higher bill is called Golden State Water, and it’s structured and regulated much like Cal Water, which serves remote parts of Sonoma and Marin and was the focus of a recent Bohemian cover story (“Wrung Dry,” May 29). It’s similar in another way, too: ratepayers complain of costs so steep they’re killing the town.

“We saw that the city could actually disappear,” McPherson says. After all, shops, restaurants and other players in the town’s tourist industry depend on water, and sky-high utility rates threaten their very existence. According to McPherson, even the school district is currently shelling out as much as $65,000 a year on what has come to be a precious and costly resource.

In May, we examined how rates often skyrocket in small towns served by investor-owned water utilities—many of them remote areas with high poverty rates. Marysville in Yuba County, for example, has a poverty rate of almost 26 percent; residents pay between $80 and $350 a month for water, according to resident Connie Walczak, and the town faces a possible rate hike of nearly 50 percent.

Unlike energy utilities, those providing water can’t spread the cost of service across a vast, statewide base. Per California’s regulating Public Utilities Commission (PUC), each community pays for its own cost of treatment and service, which means that a town of roughly 200, like Dillon Beach in Marin, can get strapped with exponentially more dollars per household than a district with thousands—or hundreds of thousands—of hookups. Dillon Beach residents compensate any way they can: showering once a week, abandoning gardens and buying only dark clothing, so they can wash it less.

But with fees leaving small districts for Cal Water’s headquarters—where the CEO drove an $85,000 car, board members were paid thousands per meeting and rate increases were requested to pay the salasries of employees who then weren’t even hired—some ratepayers we met in May felt their steep fees were unjust. In Lake County’s Lucerne, especially, a group was pushing to oust the private company entirely. A group of citizens in Marysville have filed a formal complaint with the PUC, and the town may be heading toward localization as well.

But is it possible to overthrow your water company?

McPherson is part of Ojai FLOW (Friends of Locally Owned Water), an organization also trying to reclaim its city water infrastructure. This would require eminent domain and 66 percent of the town vote, and it sounds like an underdog story too optimistic to exist off-screen: a city of just over 7,000 vs. a water company serving roughly 250,000. You do the math.

But it has been done. What’s more, according to a man whose town actually did declare independence from the company running its pipes, the smaller the community, the better.

Felton is a town of roughly 4,000 that sits along winding, redwood-lined Highway 9 east of Santa Cruz. It resembles Guerneville. Rustic cabins sit atop long bumpy driveways and line the San Lorenzo River on stilts. It’s not the kind of place you’d expect a door-to-door petition to succeed.

But it did, and according to Jim Graham, spokesperson for Felton FLOW, the reason was both simple and surprising: people knew their neighbors.

Graham says that the effort to oust California American Water, another investor-owned utility regulated by the PUC, began when the company requested a 78 percent rate increase in 2003. He estimates that bills were already twice the amount paid to the nearby public utility, San Lorenzo Valley Water District (SLVWD). So a group of ratepayers gathered at the small downtown fire district, discussing how they could take back their water—which runs cold and free through the misty state parks surrounding the town. They decided to go door-to-door.

[page]

“We walked the community three different times,” he says.

First they rang doorbells and told homeowners about the rate increase. After that, they calculated what it would cost to fund a bond measure with local property taxes and sue for eminent domain. They estimated $11 million, which worked out to about $60 a month per homeowner. Then the group printed their calculations on a flier and took it door-to-door.

Once everyone was aware of the tax increase, Graham put his background in PR to work. Walkers climbed porches again, this time collecting only the names of those who were in favor of the bond measure.

“We looked for anyone who was influential—business families, prominent families,” he recalls. “We asked them if they’d be willing to put their names on another flier.”

Because it’s such a small town, and so many people know each other, that strategy worked well. Graham recalls that when activists broadcast the third flier with 300 family names on it, homeowners scanned the list for names they knew. After the third walkthrough, a majority of the town voted to do something extraordinary—give themselves a $600-a-year property tax hike to buy their pipes.

But the water company fought back.

Nearly 10 years later, Evan Jacobs with California American Water says Felton’s water infrastructure, though locally owned, will continue to have costly maintenance issues. The reason: many of the pipes serving the mountain town were laid in the late 1800s.

“They are not saving money,” he says, referring to a rate hike of 53 percent proposed by San Lorenzo Valley Water District, the local company that took over Felton’s water, earlier this year.

“Now they’re paying the acquisition cost and facing another cost because of infrastructure,” he says.

According to Graham—and confirmed by current SLVWD manager James Mueller—the water-treatment facility was in need of major upgrades when the local company seized it.

“Specifically, there were leaks that had been reported as leaks by consumers for years and were not identified,” Mueller says.

Jacobs doesn’t contest this, but points to the age of the infrastructure, coupled with Felton’s remote wooded terrain.

“There are a lot of steep hillsides and redwood trees, which love to wrap their roots around water pipes and crack them,” he says. Cal American’s rate increase was partially proposed to fix one of the two main water lines feeding the treatment plant, he explains.

Aging infrastructure is a common problem facing small rural towns served by private water companies, Jacobs says. Without public subsidies, private companies are forced to charge the actual cost of maintaining these crumbling systems.

So, according to Jacobs, Cal American tried to inform the Felton group that their local bid wouldn’t really save any money in the long run.

But according to Graham, it was more than that—an aggressive PR strategy that included deceptive websites, astroturf groups and push polls. Graham paints it as a costly example of the company ignoring what its ratepayers obviously wanted—to break free.

In a confidential PR plan, shared with the Bohemian by Felton FLOW, Cal American states: “Our strategy is to make the road a rocky one for proponents.”

[page]

The document reads like a political campaign, outlining intentions of “making this an unpleasant experience” for the incumbent county supervisor and convincing at least one-third of the voters that localization “is a bad idea for them.”

Jacobs confirmed that the document, sent to him via email, was real.

“We wanted to show that local takeover would result in an additional tax burden for customers,” he says.

The packet contains a letter drafted for Felton homeowners. The San Lorenzo Valley Chamber of Commerce is cited, in large bold letters at the top.

“Outside organizers want to put another tax on Felton residents,” it reads, adding further down that “[t]his tax won’t pay for better schools, fire protection or police. This tax doesn’t improve anything.”

At the bottom of the letter, in miniscule font, is printed: “This letter was made possible through a grant from California American Water.”

“The water companies play dirty,” Graham says, adding later that the worst part was the push polling.

Jacobs denies that the poll, attached to the document, is in fact a push poll. A subtle form of smear campaigning, push polls begin with open-ended questions and then proceed to questions designed to slur. Negative statements that aren’t necessarily true—e.g., “If you knew so-and-so was engaged in money laundering, would you be more or less likely to vote for him/her?”—are masked as simple information gathering.

“You can decide if you think it’s a push poll,” Jacobs says.

Performed by Voter Consumer Research—which, according to the Los Angeles Times, conducted polls for the 2000 Bush campaign—it starts out with a bland question: “Do you believe things in Felton are going in the right direction, or have they gotten off on the wrong track?” It then, subtly, gets into water, asking speakers to rate California American Water as one of many “people or organizations in the news,” along with state senators and local politicians. Quickly it becomes more specific, asking about rates and local water control. While the questions do represent both sides, questions about local takeover certainly don’t have the rosiest tone. “Still other people believe . . . [l]ocal water should be under public control even at a cost of thousands of dollars in new taxes per household,” it reads.

Important to Graham at the time was how much ratepayer money funded Cal American’s campaign.

“I don’t know how much it cost, but it was not ratepayer money,” Jacobs says. He adds that the campaign was funded by shareholder money, which doesn’t come from rate increases and isn’t overseen by the public PUC.

Archives from a Tennessee newspaper in 1999 report that similar PR battles—between Cal American’s sister Tennessee American and local takeover efforts in Chattanooga and Peoria, Ill.—cost the company $4.9 million, with the majority spent on Chattanooga.

“We didn’t even spend $300,000 in the last mayoral campaign,” a woman is quoted as saying about the fight.

During that campaign, local takeover efforts failed.

Meanwhile, back in Lake County’s Lucerne, policemen patrol water meetings for crowd control, business owners talk about paying $800 a month and picketers line streets with signs that read: “Bring our water down or get out of town!!”

Craig Bach, the president of Lucerne FLOW, says there are some unique challenges facing the town—where almost 40 percent of the population lives below the federal poverty rate.

“People who have trouble putting food on the table don’t have time to organize,” he says, adding, “There are a lot of seniors here living on $800 a month or less.”

The 66-year-old, who still works as an electrical contractor, says the person doing PR for Lucerne FLOW has passed away, and that it’s simply hard to amass the support needed to fuel a local movement with so few people in town.

But he’s not hopeless. He has an appointment to speak at the local Democratic meeting, and he continues to reach out to politicians.

“I don’t have any immediate answers,” he says.

Still, according to Jim Graham, ratepayers—even in small districts—can take control of their water.

“The towns that are most successful are the small towns,” he says. “If you’re in a big town, the water company can print newspaper ads and buy time on NPR, they can send you slick fliers, but they can’t go door-to-door. We had so few people that everyone knew everyone else. Small communities can create a united front.”

[page]

AREAS OF SERVICE

Is your water utility privately owned? In some remote areas, water service is supplied by privately owned companies. If your water company is on this list, chances are your bill is higher than households on municipal utilities.

California Water Service (Cal Water)

Dillon Beach

Parts of Guerneville

Parts of Santa Rosa

Parts of Duncans Mills

Lucerne

California American Water Service (Cal American Water)

Larkfield/Wikiup

Golden State Water

Clearlake