Ten seconds.

Ten seconds is how long it takes to tie one’s shoes, or to send a text. But for a sheriff’s deputy last week, 10 seconds was all the time it took between calling in to report a suspect and then calling again to report the boy had been shot.

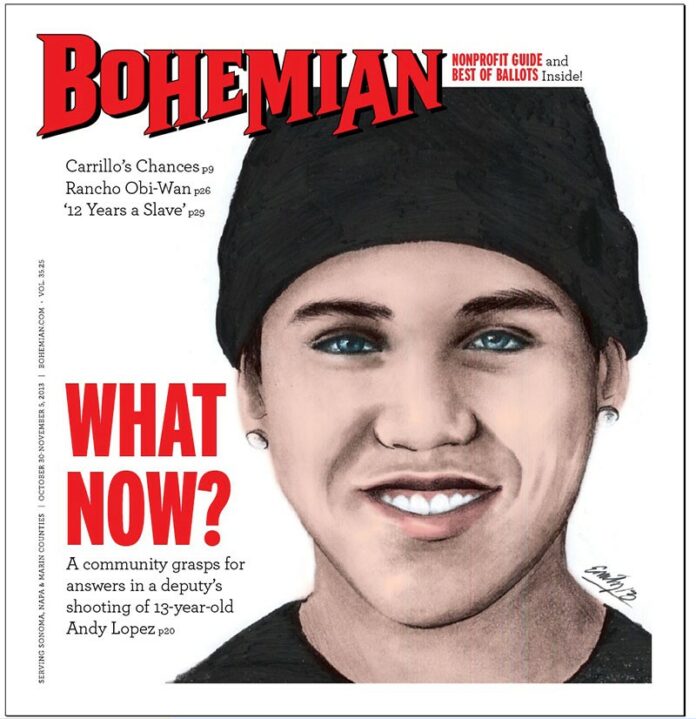

This is what we know about the shooting of 13-year-old Andy Lopez from the deputy’s perspective: that Lopez, wearing shorts and a blue hoodie, was seen by two deputies walking along Moorland Avenue holding an Airsoft gun made to look like an AK-47. That the orange tip, signifying it as fake, had been removed. That the lights of the deputies’ car came on, that the boy, from behind, was told twice to “put the gun down.” That as he moved to turn around and face the deputy, the barrel of the toy gun “was rising up and turning in his direction.”

We know all too well what happened next: that deputy Erick Gelhaus fired at Andy Lopez eight times, striking him seven times, killing him on the spot.

What we know about the shooting of Andy Lopez from witnesses’ perspectives is that Gelhaus kept firing after Andy Lopez hit the ground, according to a neighbor across the street. That he instructed Lopez to put the gun down from inside the vehicle, not outside, according to two women who were on the block. That after the deputy’s door opened, it took only three to five seconds before shots were fired, according to another man in the neighborhood.

What we know from visiting the site on Moorland Avenue is that the location of the deputies’ vehicle is still marked on the asphalt, very much behind where Andy Lopez was walking. That Gelhaus has stated he “couldn’t recall” if he identified himself as law enforcement when he called out to drop the gun. That by the SRPD’s own admission, Andy Lopez hadn’t fully turned around to see who might be calling to him before he was struck with bullets. That according to the autopsy, he was struck, among other places, in the right hip and right buttock—from behind.

In the week since the shooting of Andy Lopez, more questions than answers have arisen from a community still in shock and still struggling with how a 13-year-old carrying a toy can be killed in plain daylight. “The public expects that the investigation will be thorough and transparent,” said Sonoma County Sheriff Steve Frietas, in a prepared statement. “As sheriff, I will do all in my power to see that expectation is satisfied.”

Likewise, the Santa Rosa Police Department and District Attorney Jill Ravitch have all promised thorough, transparent investigations into the incident. Additionally, after the incident timeline and preliminary autopsy results were released last week, the FBI announced it will conduct its own independent investigation into the shooting, taking all perspectives into account.

But the perspective that’s missing is the one of Andy Lopez—and, tragically, the one person who can offer his perspective is no longer alive.

In marches, vigils and calls to action over the last week, the community has demanded—and deserves—a detailed explanation of what happened last week on Moorland Avenue. But in Sonoma County, detailed facts about officer-related shootings are often impossible to obtain.

Per longstanding protocol after officer-related shootings, the Andy Lopez shooting is being investigated internally by the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office and also by the Santa Rosa Police Department—ostensibly an independent, outside agency. But as many are quick to note, the close relationship and shared duties between these two departments negates any possibility of complete impartiality. Currently, the SRPD is being investigated by the sheriff for an incident earlier this month. How, people are correct to ask, can the SRPD be impartial to the sheriff? And how can the district attorney, a sworn representative of law enforcement, also be impartial in its own analysis?

[page]

Such questions have yet again brought up the need for a civilian review board, which could potentially have subpoena powers and could provide taxpayers with a mechanism to oversee the public servants whose salaries they pay. In fact, a civilian review board was recommended for Sonoma County by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 2000, after a one-year probe into a spate of officer-related deaths and the conflicts of interest inherent in local protocol for investigations. Civilian review was criticized by law enforcement, then as now, as unnecessary.

Even longtime activists like Mary Moore admit that civilian review boards aren’t perfect. “I am personally one of those that feels that civilian review boards have their downsides,” she says. But considering the current practice of local departments investigating each other, Moore adds, “I just don’t see that anybody would trust that process to be either transparent or accurate. We definitely need an outside eye on this.”

Longtime police-accountability activist Robert Edmonds points out that in the 26 officer-related fatal shootings that have occurred since 2000—a number that includes deaths caused by Taser—no officer has ever been convicted of any wrongdoing. Edmonds says this underscores the need for outside investigations, even while predicting that civilian review boards can create extra levels of bureaucracy—and won’t always stop complaints. “Police say they’ll be stacked with liberals who are opposed to police at all times,” Edmonds notes, “and liberals will say it’s stacked with conservatives who side with police at all times.”

Still, Edmonds says, something needs to be done to stop the cycle of citizens being shot. Looking at other models in San Francisco and beyond, a civilian review board could be set up in such a way to provide that opportunity. As Marty McReynolds of the ACLU stated last week, “Only such an independent investigation can supply the facts needed for corrective recommendations and give the public confidence in the actions of the agents pledged to protect our community.”

Sheriff Frietas asserts that the existing grand jury serves as the impartial outside body that police accountability activists continue to demand. Comprised of 19 voluntary applicants, the grand jury delivers the final report on the district attorney’s findings into officer-related shooting investigations.

But a community like that of Andy Lopez’s won’t see itself represented in the grand jury. The current grand jury, for example, is very predominantly white and over 50 years old. “Typically, grand jury membership involves a time commitment of some portion of two to three days a week,” reads the grand jury’s operational summary, and who, living in the low-income neighborhood of Moorland Avenue, has that kind of time?

The FBI will investigate the shooting, and has stated that Andy Lopez’s civil rights will be an issue in their investigation. This can hopefully address questions about the shooting’s racial implications and the marginalization of the Latino community at large in Sonoma County. Just this month, Santa Rosa police and SWAT members surrounded a house for 11 hours after reports of a man firing a gun at his wife. Why would officers wait 11 hours when dealing with a man shooting a real gun and only wait 10 seconds when dealing with a teenager carrying a replica gun? Could it be that the man was a middle-aged business developer living in Fountaingrove, instead of a teenager in a hoodie walking in a largely Latino neighborhood?

Chances are that amid the slow investigation process, more facts could come to light via a wrongful death lawsuit filed by Lopez’s family, who reportedly has hired an attorney. This could yield much more information on the shooting than is available to the public or the press, says Santa Rosa attorney Patrick Emery, who represented the family of Jeremiah Chass, a 16-year-old shot and killed by county deputies in 2007.

The wrongful death lawsuit filed by Emery on behalf of the Chass family resulted in a

$1.75 million out-of-court settlement. But it also resulted in a collection of evidence that Emery says conflicted with official reports at the time coming from the sheriff’s department, the SRPD and the Press Democrat.

That evidence was never stifled by a nondisclosure agreement; if the family wanted to, they could have released it, says Emery. “In the Chass case, my clients chose not to speak further once the case was settled. It was their choice simply to avoid further emotional upset, and that was a very emotional personal decision they made.”

[page]

Rather than shield themselves from the public, Andy’s parents, Sujey and Rodrigo Lopez, have been active in marches and vigils for their son, and have demanded that justice be served. If a wrongful death lawsuit were to be filed and evidence collected, it’s likely they would push for its release.

Currently, audio recordings from dispatch continue to be withheld by the sheriff’s department. With further details like post-incident interviews, witness accounts, depositions and the deputy’s personnel records that could come from the “discovery phase” of the legal process, “I think a wrongful death suit would be appropriate, unless there is a complete disclosure of all the facts, and those facts clearly justify what the officers did,” says Emery. “Frequently, the only way to obtain a thorough and detailed explanation of the facts is through a wrongful death suit.”

While select facts on the investigation trickle out from the SRPD, the online background of deputy Erick Gelhaus is disappearing. Gelhaus, a 24-year veteran deputy who served in Iraq and led gang-prevention and narcotics efforts for the department, had no prior civilian shooting record before last week. An avid hunter and gun enthusiast, he served as senior firearms instructor for the sheriff’s department and posted regularly to online gun forums, using his real name. While many of those posts have now disappeared, easily accessible cached pages show that Gelhaus made comments pertinent to the events of last week.

“Does anybody have or know of a location for an AK-47 nomenclature diagram?” he asked in April 2001.

In a 2008 article for S.W.A.T. magazine, Gelhaus wrote that law enforcement is a “contact sport,” and he gives a warning to his trainees: “Today is the day you may need to kill someone in order to go home.”

In 2006, Gelhaus replied to a discussion about being threatened by someone with a BB or pellet gun, and it’s indicative of his knowledge of the investigation process. “It’s going to come down to YOUR ability to articulate to law enforcement and very likely the Court that you were in fear of death or serious bodily injury,” he wrote. “I think we keep coming back to this, articulation—your ability to explain why—will be quite significant.”

Taken together, the posts show that Gelhaus was familiar with AK-47s, was prepared to kill somebody, and knew that should he ever shoot someone carrying a fake gun, the requirement to convey afterward that he feared for his life was paramount.

In a news conference last week, Lt. Paul Henry of the SRPD stated as much about Gelhaus’ testimony after the shooting. “He was able, at least in interviews with us, to articulate that he was in fear of his life, the life of his partner, and the community members in the area. And that’s why he responded in the way that he did.”

Ethan Oliver is the witness who first appeared in front of TV cameras to say that Erick Gelhaus continued to fire at Andy Lopez after the boy had fallen to the ground. Speaking in front of his house four days after the shooting, he reiterated what he saw from his front porch on Moorland Avenue.

Though the autopsy eventually bore out his statements about how many shots were fired, Oliver says that in the days following his statements on TV, he’s been targeted by law enforcement.

“I’ve been harassed real bad over this,” he says. “I’ve been arrested twice in one day, and then I just caught a bogus DUI for nothing because they said they had a report of a drunk driver, which wasn’t the case. They saw me, and then they had six cops follow me. Six cops for a traffic stop. And then twice, they got me. The other one, you know, I kind of understand where their standpoint was on that, because I got pretty extensively verbally violent with them. But to me, it’s still harassment.”

Oliver also notes that the field where Lopez was shot is a common play area for kids with toy guns, where neighborhood children “play with their paint-ball guns all the time.” Oliver’s little brother often played with Lopez, a boy that Oliver describes as a “real good kid.”

“He wanted to be a boxer, he wanted to do a lot of things. He was real friendly, real popular around the school,” Oliver says, as dozens of mourners gather nearby around a candlelit shrine where Andy Lopez was killed. “To me, I really don’t care [about being harassed]. Just as long as there’s justice for this little boy and his family.”