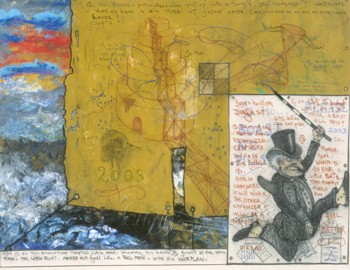

Sucker Punch: William T. Wiley’s ‘Punch Before Postulation’ showcases the curmudgeonly character with a flurry of Wiley’s musings.

Humble Pie

William T. Wiley’s long and tortured involvement in having fun

By Gretchen Giles

Ivy pushes heedlessly in through a taped-together glass window at artist William T. Wiley’s Woodacre studio, curling greenly up toward the ceiling. It’s a tawny autumn morning in West Marin, and the garden wilds thrushing around the set of small cottages that Wiley shares with his partner, Mary Hull Webster, have yet to die back and blacken in this bay tree glen by a seasonal creek. He is, as he often is, hunting about for a book in the stacks piled on the floor, his lanky frame balancing in black clogs. He finds what he’s searching for, an antique tome illustrating the antic carousings of that favorite English character, Punch.

Featured in puppet shows with his sidekick Judy, Punch screams hatefully and repeatedly whacks, and is whacked by, the other puppets to the pleasure of children delighting in seeing adult characters acting terribly badly and being immediately punished for it. And he is the newest main character in Wiley’s personal and marvelously eccentric iconography of the world, joining Mr. UnNatural, the dunce cap, the infinity symbol, the Dutch historical plaque, and the flying hourglass as shorthand symbols flavoring his art.

“He arrived with these books,” Wiley says simply, tracing the pen-and-ink illustrations of Punch on the page with his finger, “and part of it was just the gorgeous drawings.”

With the addition of a small, neat dorsal fin, Punch dominates Wiley’s current work, having crept in just this last year. And his smartly naughty ways inform the “Before Math and After Math” one-man exhibit showing through Nov. 8 at the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art.

Back at the studio, tacked up on the wall, a large canvas in progress shows Punch berating a charwoman, though this time he is an incarnation of English painter Francis Bacon’s own take on Vincent van Gogh’s Painter on the Road to Tarascon. While that’s a sweet mouthful big enough for any art historian to chew, it of course has a typically Wiley punch, this time lower-case. Through the detailed text that is among the characterizing features of his work, the charwoman impatiently shoos Punch away: “Sir, you’d better get in your van and go!”

Wiley chuckles with deep delight as he reads the text aloud. Wordplay, comical illustration, and the most basic of materials conspire together in his hands and brain to complete his artwork. A progenitor of the Bay Area “Funk” movement, so-named by curator Peter Selz in his eponymous 1967 exhibit at UC Berkeley’s University Art Museum, Wiley may be an art star, but he doesn’t dwell with any hubris in that ether.

In fact, a special evening with the artist, in which he’ll provide a slide-show retrospective of his career before picking up a guitar and playing his original songs for those gathered, is scheduled at the SMOVA for Saturday, Oct. 4. This type of humble offering, in which the 66-year-old artist not only lays his soul out on the gallery walls but then plays and sings while the audience presumably chats and sips around him, is almost shocking for a man of Wiley’s international stature. But it’s also curiously and exactly in keeping with his humble nature. His materials are those that most of us have access to: chalk and graphite and tape and glue and wire and paint and cardboard boxes. A dried leaf. A Ritz cracker container.

“I want all of these materials to remain absolutely accessible so that there’s no excuse,” he says, pointing to a drawing on the studio wall. “That’s made with pencil. That’s all. A pencil. So much beauty and it’s made with graphite. Here’s a pencil and here’s a piece of paper, and it’s made by a human being. And when it gets more and more removed from that–the more nothing you make it out of, the more magical it is. If it cost $8 million, who cares? If you’ve got that much money, you can have anything fantastic, but with a piece of tape that you can’t get off your finger . . .” he trails off.

Perhaps most surprisingly for someone whose work rarely whispers of such standards as poppy fields or hillsides, Wiley stated in a 1997 interview with the Smithsonian that he felt himself to be a landscape painter.

“That’s a way to explain in a simple way what I think I’m doing,” he says now, “which is just looking out at the landscape, and it includes the middle and the inner and the outer. I echo what’s going on at the time, emotionally, socially, politically–so I see that as a kind of total landscape.”

In marking this triumvirate of vistas, Wiley noodles around with words, adding copious amounts of punny text to his pieces, so much so that the viewer is sometimes surprised to discover how well the man draws, given that one unconsciously strains almost more to read his work than to view it as an object. It’s as though he’s muttering under his breath as he paints. “Exactly,” he nods. “It’s just what I started out doing as a kid: listening to the radio and drawing, and drawing what I was hearing, and also drawing what was in front of me.

“The editor is always there, doing stuff,” he continues. “That’s another relationship or dialogue that’s going on at the same time. Making that selection, deciding, sometimes veering away from it because it’s too personal and I don’t want to disclose who it is or what it is. And the conflict that often happens in work I show is that people say, ‘I don’t have time to read all that stuff.’ I never even think about that as a problem that someone would manufacture out of the work–what if it’s [being shown] in Italy? So I think that the piece just ought to work or not, even if a visitor couldn’t make out my handwriting.”

Much of what the handwriting concerns itself with at the “Before Math and After Math” exhibit is the U.S. conflict in Iraq, to which Wiley is vehemently opposed, though he couches his sentiments in humor. Is he concerned with alienating those who might not agree with his political stances?

“To be antiwar is to be anti-American, that’s for sure,” he says with a resigned chuckle. “And in the art-art world, there’s not a lot of people covering these issues. So I get accused of being too maximal in an art world that’s heading towards minimal. There’s enough people minimalizing,” he laughs. “That’s being covered real well.

“Another quote I can’t keep out of the work–I think it’s attributed to Mae West, she said, ‘When you tell people the truth, if you don’t make them laugh, they’ll kill ya.’ So even for my own survival, the humor has to enter just to be here, to not become rigid–literally.”

Wiley uses the chalkboard motif as a “matrix” to hang his polemics upon, painting a chalkboard image that he then letters over. “As a child growing up, visually you’re looking at [a chalkboard] a lot and I was always fascinated by it,” he explains. “The space that was created and the images that are left–and occasionally they intersect, something left over from another class–would create a kind of concrete poetry.

Wiley has variously been described as practicing “dude ranch dada” or as the father of the conceptual movement, from which mantle he comically flails. But it is perhaps what he terms his “totally haphazard relationship” with Zen practice that most defines this artist.

In trying to describe his process, he hunts again in the stacks on the floor for a book by Nobel laureate Elias Canetti on art’s sharp and ruthless nature. Looking up from the text, he summarizes, “Art’s not interested in you or your destination. It continually disappears when you try to comprehend it, apprehend it, or sell it. Or you push it in one way and it goes somewhere else. So that’s what, as an artist, you eventually have this long and tortured involvement with. What’s the next piece?

“You’re never on top of it. Only for minutes. Just aahhh–and then you know that it’s not you that’s on top of it,” he says, handing the book to the visitor, “it’s only some space that you can engage.”

‘Conversation, Guitar, and a Microbrew with William T. Wiley’ commences with a slide show retrospective of the artist’s career on Saturday, Oct. 4, from 7pm to 9pm. Slide show only, $15; slide show and reception, $50. ‘Before Math and After Math’ continues through Nov. 8. Gallery hours are Wednesday-Saturday, 10am-4pm; Sunday, 1-4pm. Nonmember admission is $2. SMOVA, at the LBC, 50 Mark West Springs Road, Santa Rosa. 707.527.0297.

From the October 2-8, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.