all music guide: intro | eric lindell | bruce cohn | charlie haden | north bay indie bands | rum diary | bob weir | earl thomas | kate wolf festival

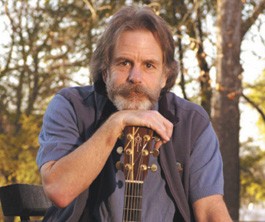

Courtesy of Alvarez

Giving back: Musician Bob Weir has always operated on the principle that giving to community is everything.

By Greg Cahill

Bob Weir is a back-slid hippie. At least that’s what a handful of west Sonoma County progressives are saying. They’re rankled that Weir–whose credentials include 30 years as a guitarist and singer with the Grateful Dead–is a bona fide member of the Bohemian Club, the elite men’s organization that stages secretive retreats each year at a sprawling Occidental camp called the Bohemian Grove.

George Bush is a member. So is Donald Rumsfeld.

As part of the annual entertainment, Weir, 58, and his longtime band mate Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart have signed on to sleep with the enemy–literally, as summer-camp bunk buddies–to influence policy makers who have been accused of all kinds scheming and conniving at the Grove. The decision to drop the A-bomb was allegedly made there. World domination ranks high on the list of summer activities at the Grove.

This year, West County progressives will reportedly be picketing Weir as he and his band RatDog appear June 9 at the Harmony Festival, a counterculture lifestyle and music festival that draws some 25,000 revelers each year to the Sonoma County Fairgrounds. Weir will not only perform but will be given a lifetime achievement award for his artistry at the North Bay Music Awards (NORBAYs), a co-production of this paper and the Harmony Fest.

And he is taking it all in stride.

Weir remains committed to the beliefs that made him a counterculture icon, despite what critics on the barricades and Internet chat rooms are saying. “I have never abandoned those principles,” he says during a phone interview from his Marin County home. “I believe in community everything! I practice that in my life. In a given year, probably 20 percent of the gigs I play are benefits, though this year the proportion has been closer to a third.

“I walk the talk. I work for the community, and the community works for me. It’s been that way for 40-some years now, and it hasn’t let me down. I think that what we discovered [in the 1960s] is that community culture is a really good working paradigm.”

While onetime Grateful Dead collaborator and protest singer Bob Dylan shies away from his role as spokesman for his generation, Weir actively supports political, social and environmental causes. He even co-authored, with his sister Wendy, a 1991 children’s book, Panther Dreams, that helped raise awareness about endangered rainforest species.

“It’s everybody’s duty to stay informed and to participate in the culture,” he says when asked about his motives. “What I’m doing is no different from what a lot of other people are doing, I’m just out there doing it, that’s all. This is my country, and if I don’t make it work, then who is going to make it work? And that goes for you and everyone else, too.

“If you want to stand back and allow everyone who wants wealth and power to run the show, then that’s what we’ll get.”

The difference between you, me and Weir is that he gets to remind corporate CEOs of that fact as they cavort under the redwoods at the Bohemian Grove while clad in women’s clothing and lipstick (cross-dressing being all the rage there).

And if Weir remains committed to the principles that helped make him a counterculture icon, he’s also committed to the freewheeling improvisational path blazed by the Dead.

“It’s the old Grateful Dead mode of operation,” he says of RatDog’s forte. “You state a theme and then take it for a little walk in the woods. Along the way, there’s going to be a lot of interaction, and people are going to reinterpret stuff on a nightly basis.”

RatDog, which started as a duo with Mill Valley bassist Rob Wasserman, marked their first gig as a full band on Aug. 8, 1995, just one day before the death of Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia. With the dissolution of the Dead, RatDog took center stage in Weir’s professional career. Since then the band members have undergone a few personnel changes, but–like the Grateful Dead–they’ve also amassed a large repertoire, so they may revisit a song only two or three times on each tour.

“You know that when a song comes up in rotation, this is your last crack at it for a while, so you really invest yourself in that evening’s interpretation of that song,” he says. “It works out real well for us. We don’t get bored; we love each song each time it comes around, and if that’s formulaic, then it’s a real good working formula.”

As for the Dead, Weir has little desire to relive the past and had no involvement in the spate of recent Dead CD reissues on the Rhino label. “I enjoy listening occasionally to what we were up to 20 years ago,” he says, “but for the most part, my whole concern is what I’m going to be doing tomorrow and next week and next month.”

The Bohemian, in conjunction with the Harmony Festival, honor Bob Weir and Bruce Cohn with Lifetime Achievement Awards at the second annual North Bay Music Awards (NORBAYs) on Friday, June 9, at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds. 1350 Bennett Valley Road, Santa Rosa. The NORBAYs begin at 5pm; the awards will be given at roughly 8pm. Free with NORBAY admission. For details, go to www.harmonyfestival.com.