It’s called spearfishing, but it’s really spear-hunting. The fish don’t come to you. You must go to them, with your finger on the trigger.

That fact became clear as soon as I dove beneath the surface into the 48-degree water in a picturesque cove north of Fort Ross. I’d been abalone diving before and once I learned to regulate my breath and stay calm, finding and prying the mollusks off rocks was relatively easy.

Spearfishing is different. While some fish hole up under rocks and stay put, many species are on the move, which means you have to first spot them and then have the wherewithal to get close enough to take aim with your speargun, all before your breath gives out and you need to surface and start over again.

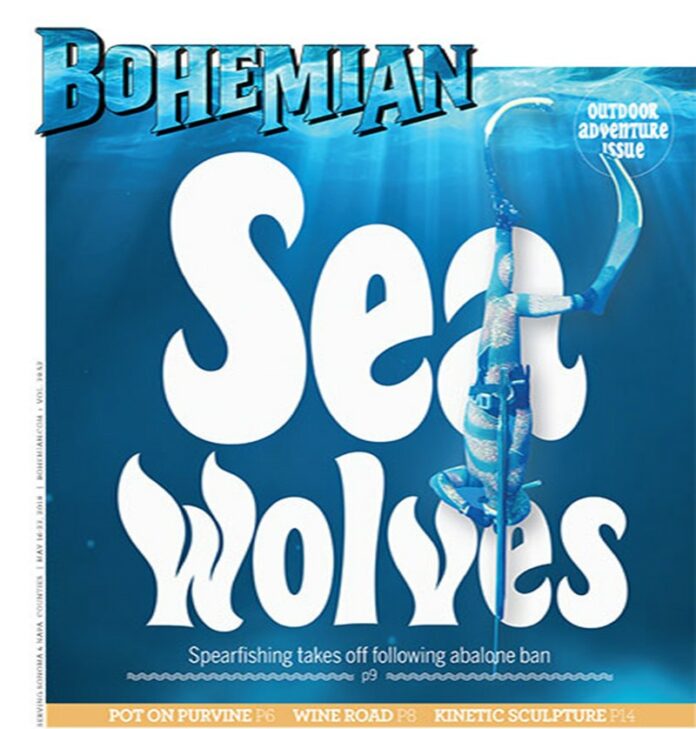

Outfitted in a 7-millimeter wetsuit, hood, booties gloves, mask, fins and a 18-pound weight belt—and toting a menacing–looking speargun—I dove into the icy water again and again in search of my prey.

But I never fired my weapon. I spotted a few rockfish darting about, but they were too small to shoot. There was no sign of the hulking lingcod I hoped to find. My visions of a grilled fish and cold beer were not to be.

It turns out spearfishing is a lot harder than diving for abalone.

My dive partner, Zeke Cissell, had better luck and plunked two black rockfish. He’s the manager at Seals Watersports in Santa Rosa and a veteran diver. Seals is Santa Rosa’s outpost for spearfishing gear as well as scuba and surfing supplies. Cissell took me out last year on my first ab dive, too. While I was hunting for abalone, he was spearfishing. He enjoys the challenge and says he likes the taste of fish better than abalone. Cleaning a fish is easier than butchering an abalone, he adds.

A few months after my first ab dive last year, state regulators closed the season to recreational divers this year in hopes of helping the embattled shellfish recover.

Now spearfishing is the only game in town for divers who want to capture their dinner. All you need is a regular sport-fishing license. Abalone diving season usually begins in April, but according to local dive shops, interest in spearfishing is spiking as seasoned abalone divers pick up spearguns and newcomers like me take up the sport.

“We’ve definitely seen an uptick,” says Tom Stone, owner of Rohnert Park’s Sonoma Coast Divers. “We have many people coming in just because of their love of the water.”

While I got skunked, I’m eager to go back. Fish or no fish, spearfishing offers passage into an underwater world most of us never get to see. While I spied precious few fish, I saw iridescent, waving anenomes, starfish and more than a few hefty abalone that will be left in peace for at least the next year, poachers notwithstanding.

But mostly what I saw were purple urchins. Thousands of them carpeted the rocks like tiny cacti. The proliferation of the spiny buggers is part of the reason for the abalone’s demise. The urchins gobbled up most of the kelp, which is abalone’s primary food source. Aided by the die-off of urchin-eating sea stars and warming ocean temperatures, the exploding population of urchins has transformed what was an undersea garden into the equivalent of a clear-cut forest.

While the underwater scene is beautiful to behold, it’s a landscape that has been transformed. Now the nacreous shells of abalone that starved to death litter the ocean floor.

On Memorial Day, the Waterman’s Alliance is organizing an urchin gathering dive at Ocean Cove to try collect as many urchins as possible in hopes of getting kelp to grow back and coax the abalone population back to health.

Fortunately, the urchins (which are edible) have not affected the rockfish population, which Stone says is growing in number thanks to the creation of California’s network of Marine Protected Areas (MPA), zones of protected marine life and habitat.

The North Bay’s MPA is the North Central California MPA, and it runs from Point Arena to Pigeon Point in San Mateo County. In addition to lingcod and black rockfish, sought-after species for spearfishing include cabezon, vermillion and sand-dwelling halibut.

For newcomers like me, Cissell recommends going out with a buddy to spots with easy access, like Stillwater Cove and Fort Ross. Better yet, take a class. Sonoma Coast Divers and Petaluma’s Red Triangle Spearfishing offer courses that teach diving and breath-holding techniques, as well as water safety.

Parviz Boostani, co-owner of the menacingly named Red Triangle Spearfishing in Petaluma, says interest in the sport is growing following the abalone ban. The shop offers a free-diving (no scuba) certification class.

“People still love to get out on the ocean,” he says. “The only alternative is spearfishing. It’s a different kind of hunt.”

OK, what about sharks? Well, they’re out there. Stone suggests avoiding drop-offs and pinnacles where great white sharks sometimes lurk. Cue the John Williams score.

Sharks are known to inhabit deep waters and ambush prey in shallower depths. But Stone says attacks are rare. “You’re more likely to die driving off a cliff getting up there” to Fort Ross, he says.

Cissell tries to not think about sharks, given the low odds of an encounter. Diving at shallower depths can further minimize the risk.

“You don’t have to go super deep to get what’s on our coast.”

Even though I was diving at 25 feet or less, I felt better facing into deeper water with the shore behind me, lest I get surprised with my back turned.

“That’s the risk,” says Boostani. “You’re in their world.”

Boostani likes to go deep and hunt in waters he knows are sketchy. After his friend was attacked by a shark in Monterey last year, he now wears a Shark Shield. The $500 device is worn around a diver’s ankle and sends out an electromagnetic pulse that is supposed to deter a hungry shark.

“That makes me feel a heck of a lot better,” he says.

For Stone, the risks and enjoyment that come with spearfishing are worth the risk, especially if you go home with dinner.

“Fresh seafood is more expensive than ever,” he says,

Heck yeah, it is.

Back in the cove with Cissell, he looked like an underwater commando with a flashlight strapped to his wrist and knife on his ankle. He uses the light to peer into dark holes and crevices in search of lunkers.

“You’re looking for a pair of eyes looking back at you.”

I saw no eyes. Cissell took pity on me after I came up empty-handed and gave me his fish. I got to enjoy fresh fish and cold beer after all. The fish were small, and made for great tacos. I’m hooked.