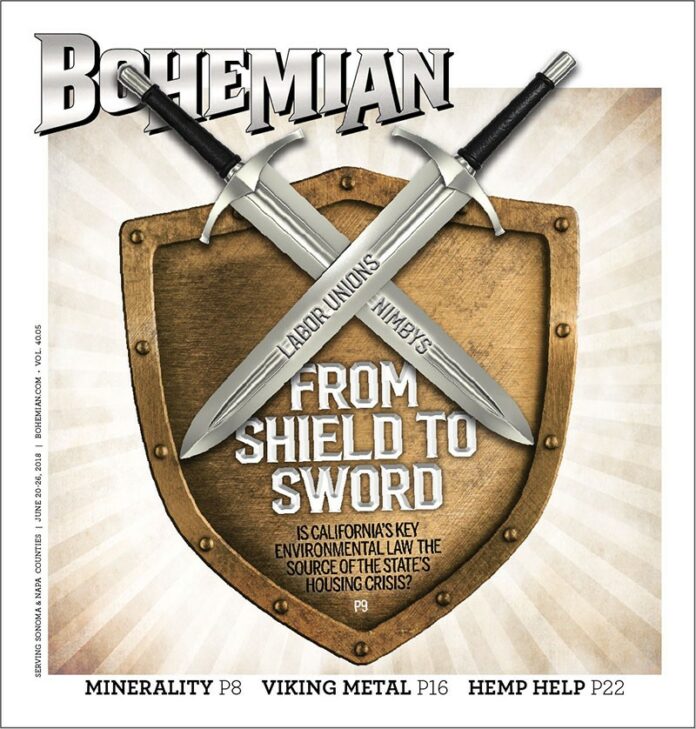

The landmark California Environmental Quality Act of 1970 was intended as a shield against construction projects that imperiled the environment. But in a case of unintended consequences, critics charge that the powerful law has been wielded as a sword by labor groups, environmentalists and neighborhood groups to defeat proposed housing developments. The result, they argue, is that a well-intentioned law has driven up the cost and lowered the supply of affordable housing in the North Bay and California at large.

In a way, this is a tale of two competing points-of-view about CEQA. In one corner, CEQA critics decry the law as a leading impediment to building transit-oriented and infill housing in the state—and especially in urban regions such as Los Angeles and the greater North Bay. That’s the gist of a recent legal study by the San Francisco law firm Holland & Knight. The analysis was published in the Hastings Environmental Law Journal.

In the other corner are supporters of CEQA who say those claims are overstated, and perhaps wildly so, and that the real driver behind the region’s struggles to deal with its affordable housing crisis, or any housing for that matter, are the local agencies (zoning boards, planning commissions) that also must sign off on any proposed development.

That’s an argument advanced in another recent report published by UC Berkeley School of Law, called “Getting It Right,” which serves as a handy counterpoint to the Holland & Knight report.

This is more than an academic debate. The discussion comes at a key moment in the North Bay, which is still reeling from last year’s devastating wildfires that destroyed more than 5,000 homes in the region, making an acute housing crisis even worse.

A bill co-sponsored by State Assemblyman Jim Wood (AB 2267) “would exempt from the requirements of CEQA specified actions and approvals taken between January 1, 2019, and January 1, 2024.” According to a legislative analysis, the bill sets out to determine whether Santa Rosa and Sonoma County would need additional legislative support from Sacramento to ensure the rebuilding process isn’t slowed by red tape. Santa Rosa has already passed an ordinance, its Resilient City Development Measure, that set the stage for the broader CEQA exemptions for the region now under contemplation in Sacramento.

Baked into Wood’s bill is an assertion that generally jibes with the Berkeley study: CEQA-related lawsuits are actually not that common, and that exempting Sonoma County and Santa Rosa from CEQA won’t lead to a rash of lawsuits. “Although certain interests believe CEQA litigation to be a swathing impediment to some projects, the numbers . . . indicate otherwise,” says a Senate Environmental Quality Committee report on the Wood bill from June 11, which further notes that “the volume of CEQA litigation is low considering the thousands of projects subject to CEQA review.”

Among other supporters, the Wood bill is favored by the city of Santa Rosa. The Sierra Club has opposed it, and the local Greenbelt Alliance has not taken a stand on it.

Gov. Jerry Brown has been on the side making the “swathing impediment” argument when it comes to CEQA’s intersection with organized labor. In past comments, Brown put the blame for any CEQA abuse squarely on the state’s powerful Building Trades Council, as highlighted in the Holland & Knight report. Brown told the UCLA magazine Blueprint in 2016 that CEQA reform is impossible in California, since “the unions won’t let you because they use it as a hammer to get project labor agreements.” Project labor agreements (PLAs) guarantee a development project will use union labor.

Unsurprisingly, local labor leaders do not share the viewpoint that PLAs are contributing to the North Bay housing crisis. “We’ve supported CEQA for years and years,” says Jack Buckhorn, executive director of the North Bay Labor Council, AFL-CIO. He doesn’t support CEQA reform, he says, because there is nothing to reform when it comes to PLAs and organized labor. “It’s an easy target to say labor is the problem, but all the research we’ve done—it doesn’t prevent projects from going forward. They are making this stuff up to try and jack labor.”

Buckhorn says he’s unaware of Brown’s comment to the UCLA paper, but says, “We don’t buy into these arguments. I reject the argument that projects are abandoned or not built because of abuse of CEQA.”

Marty Bennett of North Bay Jobs for Justice echoes Buckhorn’s pushback.

“We feel in terms of ensuring highly skilled, highly qualified labor, that PLAs are in the best interests of the public.”

A PLA was adopted in advance of a recent development project undertaken at Santa Rosa Junior College, and if securing a union contract with good pay serves to delay a project, then so be it, he says.

“A PLA can cause delays in the development process, but in terms of serving the public interest, those delays are well worth the time—particularly in terms of environmental consequences.”

[page]

In its report, Holland & Knight tees off on what it perceives as Brown’s lack of action on the CEQA front. The law firm has represented numerous developers. Its years-long study of CEQA suits and their impact on development projects focuses on post-approval, sometimes “frivolous” lawsuits which the author claims slow down projects across the state.

For developers without unlimited budgets to fight legal challenges to their plans, the historical “frivolous lawsuit” argument is that the late-game lawsuits can delay a process that’s just been completed and approved by local or state agencies—and send the developer back to the drawing board to deal with challenges filed to its environmental impact review. The process serves to drive up the cost of development.

As the accompanying chart shows, the CEQA process is a long and detailed road toward final approval, with multiple layers of public participation and agency review. While citizen-led CEQA lawsuits by themselves can’t put an end to a project, they can add costs, or force a developer to back out if legal fees become onerous—or in the case of housing, try to recoup costs by increasing the sale price.

Individuals have the right to sue under CEQA rules—and even sue anonymously. Inasmuch as the multitiered permitting process at many North Bay city halls and supervisors’ chambers has also served to slow or otherwise derail housing development, Holland & Knight argues that so, too, do CEQA-centric suits launched by organized labor, NIMBY neighbors or competing business interests.

But the Berkeley Law report notes that “what drives whether and how environmental review occurs for residential projects is local land use law“ (italics added). Delays in a project’s approval, it argues, can typically be drawn back to local review and not a last-gasp, anonymous lawsuit. The Berkeley study looked at residential development projects in San Francisco, San Jose, Redwood City, Palo Alto and Oakland.

The Holland & Knight study, meanwhile, keys in on the North Bay and Los Angeles, and identifies Marin County as one of the wealthiest counties in the state, with the oldest average population of any county. The study also indicates that Marin County is ripe with “NIMBY-ism” when it comes to residents swinging the sword of CEQA at development projects they don’t like.

The firm identifies that two biggest sources of CEQA lawsuits in the state are in “transit-oriented development” projects and infill projects in established neighborhoods. Those projects are often interchangeable. That development emphasis also happen to be the most cited “smart growth” strategy in the North Bay by civic leaders, environmentalists and developers—and also from well-meaning residents who are otherwise committed to smart growth, but in someone else’s neighborhood.

High-density development along a transportation corridor like Highway 101 aids in the containment of sprawl, may help the state meet its greenhouse-gas reduction goals and undercuts against the “trade parade” phenomenon of commuting workers, where people cannot afford to live where they work and must drive long distances. Jennifer Hernandez, author of the Holland & Knight study, notes the irony of climate-change-conscious Marin County elders opposing public policies that are designed to beat back climate change.

“NIMBYs are often progressive, environmentally minded individuals who believe in climate action and recognize that sprawl is unsustainable,” she writes. “They just want to preserve the look and feel of the neighborhood they call home.”

The study drills down on how some CEQA suits have handcuffed municipalities beholden to the California mandate of a growing economy, a healthy environment and a steady supply of affordable housing.

Meanwhile, the region’s affordable-housing crisis continues apace, and is now met with the urgency of the fire-wrought destruction of more than 5,000 homes to go along with skyrocketing rents and real estate costs across the entire Bay Area.

The NIMBY anti-development phenomenon has been met by a pro-development and millennial-driven YIMBY culture in San Francisco that’s supportive of big new developments. But the issues in San Francisco are not the same as those in Marin County or the North Bay.

The YIMBY movement, recently detailed in an in-depth In These Times piece, sprouted in San Francisco along with the advent of Google buses ferrying a well-heeled tech sector to their Silicon Valley cubicles, and as such, the YIMBY push in the city is ultimately a pro-gentrification push. Its adherents have supported large residential development projects in the Mission District and other San Francisco communities whose historical demographic has been poor, gay or Latino (or all three).

The San Francisco gentrification script is flipped in the North Bay, especially in Marin, where an older class of retirees works to keep its neighborhoods intact and free from high-density development—and historically free even of granny units, or accessory units, in existing homes.

[page]

Some CEQA suits have been brought against homeowners who want to add an accessory unit to an existing home. As Hernandez notes, those units don’t in any way expand the footprint of the home, since they typically transform existing space in a home into an apartment. “Even this most modest of changes to existing neighborhoods has prompted CEQA lawsuits against individual units,” she writes, “and against local zoning regulations that allow such units to be constructed.”

The San Francisco–based Bridge Housing Corporation ran into a buzzsaw of opposition in Marin County in 2016 when it tried to build an affordable-housing development along the Highway 101 corridor in Marinwood. The organization has built numerous affordable and market-based infill housing projects from Seattle to Santa Rosa, Marin City and San Rafael.

The company says the North Bay presents its own special challenges, given the CEQA overlay and disposition of some residents.

“It is tricky up there, to be honest,” says Bridge Housing CEO Cynthia Parker of the North Bay. “The CEQA is a device that tends to be used by a number of folks, including those who are concerned about ‘not in my backyard.'”

Much of the opposition to affordable housing, Parker says, is a push for low-density housing—or no housing at all. “The challenge with CEQA is the costs are high in the North Bay, labor is expensive all over, but when you couple that with an extreme desire for low density or lower density, then you don’t have quite the economy of scale to build and develop and manage.”

In 2014, Bridge Housing set out to re-develop a debris-strewn grocery store parking lot in Marinwood and wound up spending about $600,000 on its environmental review—then didn’t build at all. Opponents prevailed in shutting down the Bridge Housing plan after it had gone through the environmental review.

“We as a matter of course go through a full CEQA process on each and every project that is brand-new,” Parker says. “We want to bulletproof our projects. If people want to make a challenge, we’ve gone through the environmental and siting—it takes a year to 18 months to go through the full CEQA process.”

But all the due diligence in the world was no match for the Marinwood neighbors, who focused their ire on the pro-development stance then taken by former Marin County Supervisor Susan Adams, who lost her seat over the set-to on election day that year as opponents of the proposal prevailed.

“We went through quite a process,” recalls Parker, as Bridge Housing set out to develop the property and add a couple dozen units of housing. “We were going to put in market-rate as well as affordable housing. We really intended for it to be housing for middle income,” she says, but the firm eventually withdrew its proposal, given the local opposition. “There was quite a bit of pushback, and there were political ramifications,” she recalls, “as a county supervisor lost her seat over it.”

Bridge Housing had another recent run-in with the neighbors, in the city of Napa, when the company set out in 2013 to redevelop the site of the abandoned Sunshine Assisted Living center on Valle Verde Drive. After several years of local pushback from residents, Bridge Housing abandoned this plan, too.

The city of Napa approved the company’s plan to build the housing complex in 2013, and the organization planned to rehab an existing building on the site that had fallen into disrepair, and provide dozens of new units in a county with a housing-vacancy rate that hovers between zero and 2 percent.

Bridge Housing withdrew its plans for what it called Napa Creekside, but not before the organization spent some

$2.5 million, says Parker, including $1.5 million in legal fees to fight against local opponents, who highlighted the proposed project’s density and proximity to the nearby Salvador Creek. Letters to the city of Napa highlight residents’ concern about the fish, the environment, the traffic and the number of housing units in the plan.

The remaining $1 million was spent on the planning process, Parker says. Faced with opposition and a successful legal challenge by opponents in Napa County Superior Court, Bridge Housing and the city of Napa bailed out on the Valle Verde project—before an EIR had even been completed. “At the end of the day, there were two neighbors that were carrying the ball and one of them was an attorney,” Parker recalls. Bridge abandoned the plan in 2016 and sold the land to the Napa-based Peter A. & Vernice H. Gasser Foundation for $5 million. Lark Ferrell, manager of the Napa Housing Authority, said CEQA was the culprit in the disappointing defeat of an affordable-housing project years in the making. She told the local Napa Valley Register in 2016, “I think there’s a lot of support in the community for affordable housing. It’s just unfortunate there was a neighbor who, through CEQA . . . was able to derail this project.”

Ironically, in its proposal, Gasser is calling for an even bigger footprint with more housing units than the Bridge Housing plan—and with an emphasis on housing a highly visible and vulnerable population of the formerly homeless.

As it did with the Bridge plan, the city of Napa has approved the Gasser Foundation proposal, which would ultimately bring close to 90 new housing units to the now-abandoned area, spread over two buildings, along with on-site supportive services at one of them to help with the residents that would populate the rehabilitated senior center facility. The project would have two parts: a new affordable-housing project with 24 units, and the remodeled senior center with 66 units of permanent supportive housing. Their building application has been submitted with the city, says Cassandra Walker, housing consultant at the foundation, and the next step is to conduct an environmental impact review.

How will Gasser succeed where Bridge Housing failed?

“We’re trying to be transparent and open,” Walker says. “We’ve met with the neighbors twice already.”

Time will tell how the neighbors respond, and whether CEQA will be the sword or the shield in this latest development battle in the North Bay.