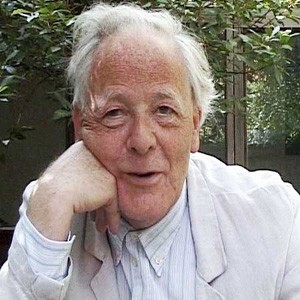

Philosopher: German filmmaker Hans Jürgen Syberberg.

Blue Danube

New film shows how Heidegger got out of the boat

By Matt Pamatmat

Philosophy, like any discipline, has its dark side, the shadows and closeted skeletons among its illustrious achievements. One of the most puzzling and troubling is why one of its best and brightest, Martin Heidegger, turned unapologetically and without real explanation to Nazism. The Ister, an Australian documentary screening March 10 at the Rafael, uses Heidegger’s 1942 lecture course on the 18th-century German lyrical poet Friedrich Hölderlin as an inspiration to journey up the Danube to the sometimes dark heart of European civilization and human existence in general, fascistic warts and all. In the heady vein of such chew-on-this films as Mindwalk, Waking Life, Altered States and even What the #$*! Do We Know?, The Ister runs 189 minutes in three languages with an intermission, à la 2001: A Space Odyssey, offered to better digest its rich, conceptual stew.

The film features interviews with prominent French thinkers Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, and includes Bernard Stiegler, who collaborated with the late Jacques Derrida on the prophetic and deep dialogue Echographies of Television. Stiegler’s own journey to philosophy is noteworthy: he spent five years in prison for armed robbery, and during this time, became a philosopher.

The film also features renegade German filmmaker Hans Jürgen Syberberg and references to such heavy-hitting Western philosophers as Plato, Nietzsche and Husserl. France, perhaps more than any other country, has contributed heavily and headily to philosophy in the last two centuries.

In these mind-numbing times of war-for-little-reason and a general dumbing down of culture, it’s nice to know someone is still thinking. Drawing widely for its influences, The Ister cites Syberberg’s own seven-hour epic, the 1977 film Our Hitler: A Film from Germany, for inspiration. Syberberg is a formidable auteur; having lived under Nazism, Stalinism and capitalism, the man knows a few things about life, believing Hitler to be the “subject” of the 20th century.

Hölderlin–an obscure schizophrenic who died unknown until the similarly troubled Nietzsche rediscovered his legacy and championed him as the best poet after Goethe–wrote the original poem “The Ister” in the late 1700s and is the jumping off point for the film’s metaphorical and literal journey upriver. Heidegger enthusiastically lectured on Hölderlin, saying that “Poetry is the establishment of Being by means of the word.” And, as with Nietzsche, Hölderlin’s work was embraced by the Third Reich (although, ironically, the hero in his poem “Hyperion” left his home country because of its despotism).

Part documentary, part philosophical treatise, The Ister slowly travels the Danube’s length, using the artifacts of humanity’s imposition on the earth to underscore Heidegger’s most basic philosophical tenets concerning our necessary destruction of nature. Heidegger’s life shows that even the smartest minds are susceptible to hatred and a fondness for authoritarianism, the enemy of mental and physical freedom.

As in that famous scene in Apocalypse Now where Capt. Willard discovers that Kurtz had advised the U.S. Army to “exterminate all the brutes,” Heidegger too wanted to exterminate all the undesirables; and in fact, Heidegger got out of the boat. His pro-Nazi turn provided fascistic strains to an otherwise ecological, evocative, beautiful, sometimes mystical philosophy.

‘The Ister’ screens on Friday, March 10, at the Smith Rafael Film Center, 1118 Fourth St., San Rafael. 415.454.1222.

From the March 8-14, 2006 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

© 2006 Metro Publishing Inc.