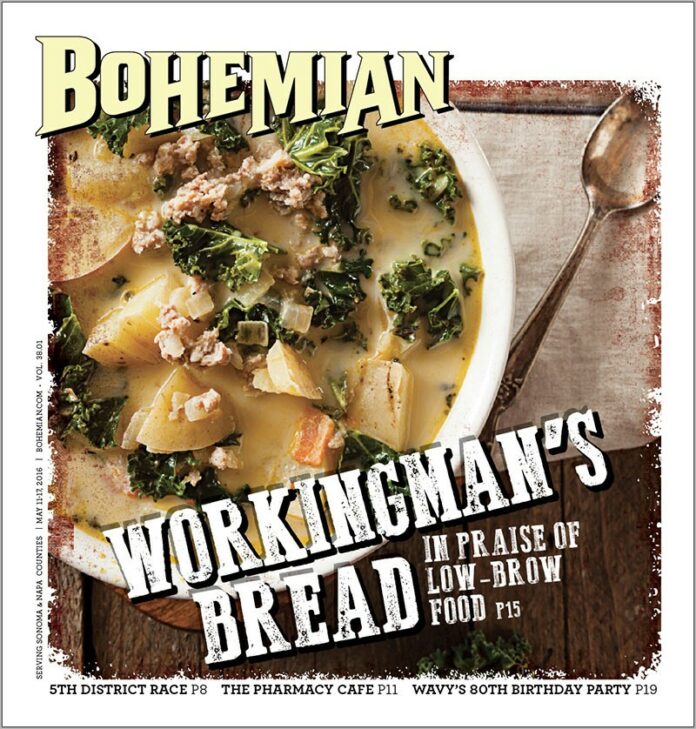

The soup has crossed the 30-ingredient line, but is still missing something; it’s a little bland, it needs help, some key but as-yet-unidentified addition that will bring it all home.

I open the refrigerator door, but every last scrap of vegetable has been scoured from the produce bin, given a bath and a trim, and chucked into the simmering pot, which now bubbles and froths, casting a fragrant steam through my silent cottage.

It’s quite a rolling experiment in kitchen frugality and efficiency—the sort of thing you do when the wolf is at the door and the refrigerator’s brimming at the edge of stinky decadence with uncooked gatherings. You cook that wolf, as the protean foodie M. F. K. Fisher famously wrote in 1942. My aunt would not have been interested—her culinary tastes lined up more with the likes of Guy Fieri, and this soup is coming in as a self-involved exercise in the creation of sanctimonious medicine. You should have seen my aunt the time I suggested she become a vegan, after the doctors removed a foot of her large intestine. That just wasn’t going to happen, and she’d have thrown all those vegetables away if they’d been in her fridge.

The red potatoes are a little soft but, hey, I want them to break down and become one with the broth, so in they go. I find two half-cut onions from previous stovetop adventures, brown and dry at the fragrant edge but salvageable at the core. I save from oblivion a trio of delicious, withered parsnips at the bottom of the vegetable box, along with some wee old sugar beets I’d forgotten about, and a wad of old butter stuck to a jar of salsa. It goes on and on like this down to the last wilt of parsley, every damned daikon and flaccid carrot—in you go!

But the soup, sadly, still isn’t quite there yet, after hours of simmering and lots of salt to ramp up the flavor factor. I reach in the fridge for another ingredient-grab and poach that box of blue-tinged local eggs, crack three of them right there into the bubbling mess. A light stir, keep those yolks intact. Then I find another onion wedged between an old half-bagel smeared with peanut butter and an empty mayo jar.

Up to this point, the soup has been a meatless and generally local and organic affair, with allowances for, say, that half-bag of Trader Joe’s shredded Brussels sprouts, which kicked off the soup hours earlier as ingredient number one, along with some similarly shredded broccoli from TJ’s.

I peer into the freezer for another hopeful look, and locate some frozen ginger on the door and run it through the grater and into the soup. I take another look and rummage around the freezer, and then—there it is, emerging like a vision from my blue-collar family roots: the key ingredient, lost under a frozen loaf of flavorless spelt bread, something I used to see in my late Aunt Mary’s freezer. Total white-trash trayf. The soup needs some of that.

I pull the red bag out of the freezer and stand over the soup pot awhile and think about Don DeLillo and a scene at the beginning of his novel Running Dog. Two detectives have just come onto a murder scene in an apartment:

“I don’t know what it is but with me the body’s in the kitchen. Always the kitchen.”

“Poor people like to be close to the food.”

“What do you think, seriously here, one entry?”

“They don’t like to stray from the food, even in the middle of a knife fight.”

II

If I had told Aunt Mary I had gone to Garlic Johnny’s in Santa Rosa? I could only imagine the conversation that would ensue. Was he there?! Did you meet him?! What did you eat?!?

Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives was one of Mary’s favorite television shows—right up there with Dancing with the Stars and Atlanta Braves baseball on TBS. It was one of those shows where, if I dared to call my aunt while Guy Fieri’s Food Network hit was on the air, I’d get a quick and harried order to “call back later, Tommy! Guy’s on!”

I was waiting on a meeting in the late afternoon at Johnny Garlic’s in Santa Rosa recently, Fieri’s formerly co-partnered joint in his home turf, out on Farmers Lane at Neotomas. Fieri’s not there anymore, and neither is Aunt Mary, who died just over a year ago. I’ll have these funny imagined what-if conversations with myself in the car, and I know she’d have gone totally nuts if she knew I was headed to Johnny Garlic’s.

And Fieri’s signature, branded dishes are still part of the menu, even though Fieri is no longer a partner in the business. The Fieri menu holdovers are highlighted as Guy’s Thangs or something like that on the menu—and the biggest jumbo signature dish of them all is, of course, his elaborately comforting and award-winning burger.

I visited the place in the in-between time before dinner; there was more staff than patrons and a kind of pre-bustle feel filled the air. It was just me for a while before a family four-top came in. I eased back alone and checked out the three televisions that offered sports, noted that the lemonade and iced coffee were both tasty, as was the boar special offered on a board and in the menu proper. The pig-with-apples dish is sort of a he-man offering that lends to a feeling here of sub-exotic culinary survivalism of the Anthony-Bourdain-meets-Bear-Grylls variety, if such a thing can be imagined. You’re not slaying that boar, but they sure make you feel as though you did at Johnny Garlic’s.

But there’s another hybrid feel to tough-guy, micro-chain Johnny Garlic’s (there are two other locations): its everyman signage and slick, fun menu clearly offer mass-market aspirations that would bespeak a celebrity starchild fronting the place, even if he’s nowhere to be seen. Sorry, Aunt Mary.

Even the receipt can’t decide whether, moving forward in the post-Fieri era, this place is “Johnny Garlic’s” or “Johnny’s Garlic.” And that, to me, is a kind of homey, appreciated touch.

I read a foodie story online recently that wondered what happened to the food-tower trend of the 1990s? Gee, I wonder. It’s right here at Johnny Garlic’s, whose burger represents a recasting of the trend from its 1990s haute cuisine pretensions to an everyman theme in this era of reality TV and blue-collar how-to hits of the Dirty Jobs persuasion.

Aunt Mary would not have cared about any of that gibberish and would have changed the subject to when was I going to try out for Jeopardy. She would have asked after that burger, and she would really have wanted to know: What happened with Guy?

[page]

The mac’n’cheese bacon burger, at its most rarefied state of stacked Guyness, contains 22 ingredients, a whole bunch of fromage among them to gild the lily. The burger is a steaming pile of comfort on a brioche bun slathered with garlic, and there is no way you are picking this thing up and taking a bite, unless you are drunk.

Lift this burger at your peril, and watch as the Donkey sauce—Fieri’s siggie combination of mayonnaise, Worcestershire, mustard and roasted garlic—ruins your shirt, and quite possibly your mood. But the masses have spoken, again and again, with awards and endless greasy-lip accolades from the likes of Rachel Ray.

Properly dissected, the burger is a delicious encounter with varied flavors, lightly intermingled in the separation. The bacon, for example, is revealed as a full-flavored glory of smokiness met with a hint of dripping cheese-tang excess.

As for Guy Fieri himself, if I was forced to explain the situation to Aunt Mary, it seems that he was kind of run out of his own hometown. His proposed winery/event center conjured images of unhinged biker bacchanals and terrified citizenry forced to endure Twisted Sister winetasting events. The burger can stay, but Guy’s got to go. And so he went.

Aunt Mary wouldn’t have liked that version of events. She loved Guy, and I worried that she loved him more than she loved me.

Who was I in the face of Fieri’s latest Emmy-winning, gullet-shove moment of high-volume mastication? The grunts, the groans, the shouts—Aunt Mary shouted right along with him, squealed with delight at his high-critic “This is good” observations and badgered me about when I’d get my own act together, which to Aunt Mary meant: “You should go on Jeopardy.”

I was the college-educated nephew in the face of Aunt Mary’s love of lumpen couch potatoes, and Fieri was so burly and accessible, I never had a chance.

He occupied the highest pinnacle of comforting anti-intellectualism that’s all over TV these days, where blue-collar hit shows depict the dirty parts of life with heroic panache. With Guy, you also saw the sausage being made. It was kind of disgusting to behold the full demonic frenzy of Fieri’s assault on meat, an assessment about which Aunt Mary would no doubt take issue.

We shared a lot of meals at and near Aunt Mary’s condo outside of New Orleans over the years; we watched her favorite TV shows on Sundays with the nuked turkey meatloaf and the iceberg salad with the Dollar Store dressing; we slammed the heavy and rich buffet at the Piccadilly and gorged to the heights of mad spectacle at mighty Golden Corral; and we settled on Chinese lo mein that was right out the door when no-one felt like cooking or driving. One thing was for sure: Aunt Mary never let me cook. That was Guy’s job.

III

The simmer has come to a full boil and the soup is all but ready for its final desecration—or, more fairly, its necessary leavening with the rich, old spice of the blue-collar palate-pleaser.

We’re at 40 ingredients and counting this Sunday afternoon, the Braves are playing the Mets and they are losing—and this would have been a day I headed to Aunt Mary’s for dinner. Sundays are for family and what you make of it, and the meals we enjoyed together weren’t “comfort food” in the sense of some superficial and meaningless “authenticity” around cheese and macaroni. But they were comforting in the sense of your soul and what it craves—which, above all else, is connection. A connection with your world, with the people closest to you, with strangers who then become friends.

I lived in a neighborhood in New Orleans that Aunt Mary did not approve of. That isn’t saying anything, since she didn’t approve of any New Orleans neighborhood, whether I lived in it or not. But Hollygrove was a fine place to live, and I used to frequent the local Dollar Store and a corner market pretty often.

The market was one of those tight-corner grocers that had a meat-and-sandwich counter in the back and offered various options for boxes of meat-for-the-week. You could get the one with the beef liver, the turkey necks and the ham hocks, or you might load up on a box with chopped meat, a bag of chicken wings and some pork chops. It is fair to say that none of this meat enjoyed any free-range time, and the living conditions were probably deplorable. But the food was cheap and plentiful; at the Dollar General, it was cheap and plentiful, but you couldn’t actually call some of that canned stuff “food,” though I ate it anyway.

Right down the street from these places there was a polar opposite encounter with food. The Hollygrove Market and Farm grew and offered an array of organic foods from regional farms and ranches. I volunteered there for a few months and they’d let me load up a big box with food at the end of your shift—oranges, jars of honey, herbs, yams, lots of great goodies to fill the unemployed larder.

I’d make collard greens and kale from the farm in the skillet, and throw in a turkey neck or two from the hoochie mart to give it the proper balance of conceits.

IV

I was reading Allen Ginsberg’s “A Supermarket in California” recently, a poem that finds the great Beat poet imagining Walt Whitman in a neon-lit California grocery store, among the cans and the vegetables.

Where will they go when the store closes, Ginsberg asks:

Will we walk all night through solitary streets? The trees add shade to shade, lights out in the houses, we’ll both be lonely.

Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love past blue automobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?

I’m standing over the simmering pot, in my silent cottage with the contents of the red bag ready to go. The first little bits pour out, and then the full pour, the gushing of garbage that is nonetheless so very vital and comforting.

Mmmm, who doesn’t love them some Jimmy Dean sausage in what would otherwise be bland if disgustingly healthy soup? I know Aunt Mary would, and Guy, too.

Dinner is served.