With the financial and human costs of climate change-fueled natural disasters rising rapidly, a new book invites Californians to reimagine their relationship with the state’s glorious and ever-changing coastline.

Rosanna Xia, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, has spent the past few years traveling up and down California’s 1,200-mile border with the Pacific Ocean, speaking to residents, politicians, academics and public officials about the various challenges posed by sea level rise.

Xia’s experiences are documented in her forthcoming book, California Against the Sea: Visions for Our Vanishing Coastline. Sonoma County’s coast and Marin City both make appearances.

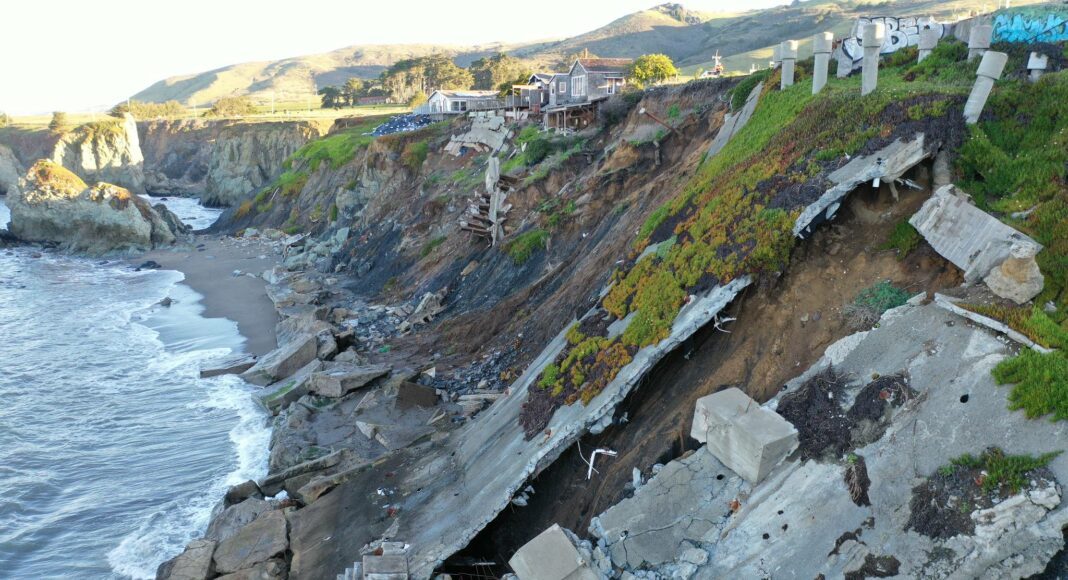

While many residents’ first instinct is often to fight to maintain the human-designated coastline with ever-more costly feats of engineering, California Against the Sea suggests that we humans should try a more humble—and hopefully less-costly—approach.

“Rather than confront the water as though it’s our doom, can we reframe the sea level rise as an opportunity—an opportunity to mend our refractured relationship with the shore?” Xia asks in the book’s introduction.

This reporter spoke to Xia by phone recently. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Will Carruthers: One of the things that I appreciated about the book is that you highlight that many of the development decisions that led to modern day California were made on the human time scale, not the Earth’s, which is obviously much longer. Why is that framing important to you?

Rosanna Xia: I love that that resonated with you. So often, our stories start with, you know, Western settlement, when the story of California began in the 1850s. So what does it mean to start before then?

The book opens with the Chumash, who have been along the coast from modern-day Malibu all the way to the southern edges of Big Sur for thousands of years. And then beyond that, geologically, the ocean and the coast have been here for thousands and thousands of years. I tried to put into perspective for readers and myself that we are mere humans on the edge of this massive edge where land meets the most gigantic ocean on this planet.

Something that humbles me every time I’m out by the water is the fact that the coast never looks the same twice. We might hide it a little bit better in some places, you know, down along Santa Monica near where I am, where sand gets brought in to help fill out the beaches and we actually rake and flatten the beaches. But the coastline itself is this incredibly dynamic space between land and ocean. This kind of tension between the two and also the marriage between the two has been in existence long before we arrived. So I think being able to capture that and establish that and really help readers reorient in that way was really powerful for me.

To start there felt like the right place to start and then, from there, let’s talk about how we got to where we are today, where we’re struggling with all of these things that we want from the coast that are in conflict with each other. And then add climate change to all that and ask, ‘Where do we go from here?’

WC: The other thing that stuck out to me was the tendency to talk about our relationship with the sea using war-like metaphors. For instance, managed retreat, the concept of moving homes and other human infrastructure out of harm’s way, is seen as a defeat while building a seawall is seen as fighting back and therefore more noble. However, on the longer time scale, humans, or at least our buildings, don’t stand much of a chance in that fight. Can you talk about this framing question?

RX: Once you see the number of ways we frame climate change using war metaphors, you’ll never be able to unsee it. Colloquially people will say, ‘the fight against climate change.’ My book’s title is guilty of this, but I’d say, once you get to the end of the book, it goes beyond that.

This idea of building a seawall versus managed retreat is such a black and white binary that we’ve kind of locked ourselves into when we start debating the adaptation strategies to sea level rise. There’s a lot of gray in between these two binaries, but these two extremes are what we’ve really spiraled into.

The seawall approach is the defend in place, we shall hold this fort forever kind of approach. Meanwhile, talk to anyone who has worked in the managed retreat space, and they’ll say, ‘This term needs a rebranding.’ The word ‘retreat’ just does not serve something emotionally in a lot of people, and it just feels very un-American to retreat from something. That’s a framing issue.

Ultimately though, the concept of managed retreat is just acknowledging that the ocean is moving inland, the coastline is supposed to move inland with it and we’re supposed to move with the coastline. This is something that has been happening for millions of years.

This book is asking the reader to reconsider our relationship to the ocean. Do we actually need to be at war with the ocean? Or can we work with it? Can we reach a point of deeper reciprocity with the natural processes along the coastline?

WC: The book also covers the passage of the California Coastal Act of 1976, a state law which has governed most of the development on the coast for the past few decades. Can you summarize how that came about and its origins in Sonoma County?

RX: The Coastal Act of 1976 is this pretty remarkable law that was started with a statewide ballot measure. It really made this philosophical stand that the coast can’t be owned by anybody, and therefore it belongs to everybody. As a result, there is no such thing as a private beach in California. This idea that we’re supposed to share this natural resource and that the coast and the beach itself is a broader public good, those concepts were enshrined by law with the Coastal Act of 1976.

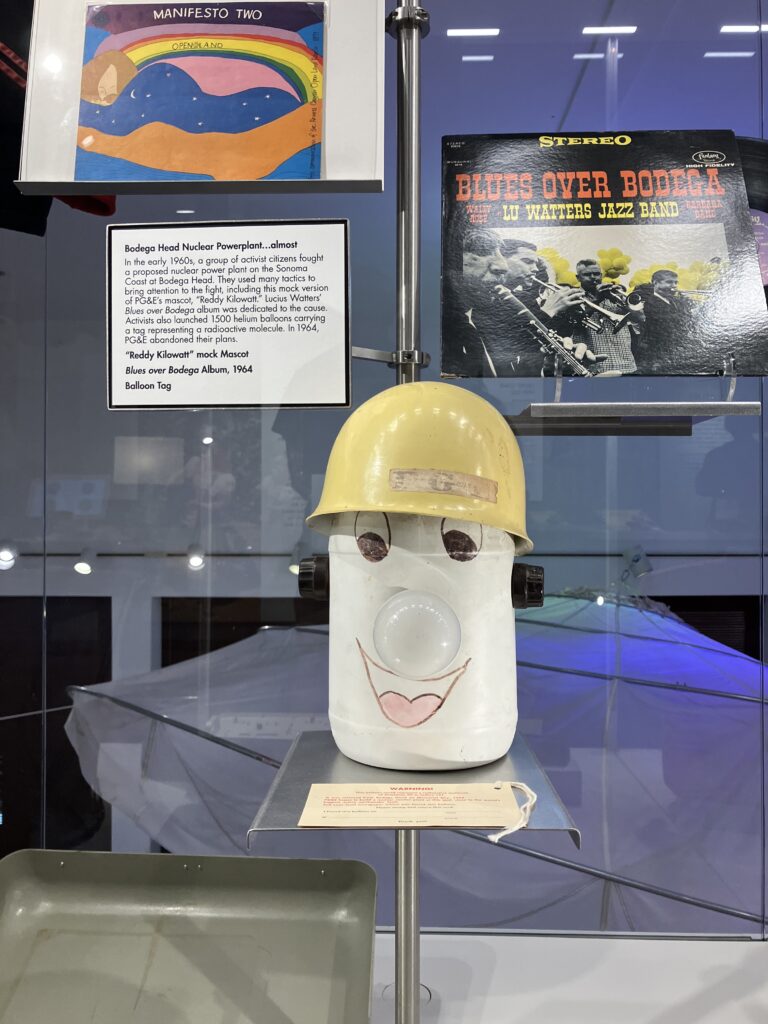

The movement to get this law passed began in Sonoma County. There were a number of projects that were being proposed at that time that really just stirred the community. One of them was the proposed nuclear facility on Bodega Head. A number of folks gathered together and stopped the project. But I think what they realized in the process was that stopping the project in one location wouldn’t prevent the developers, the utilities, the bigger corporations from building it at another part of the coast where there was a more accommodating City Council, where the politics were better or where the community had less power to fight it.

From that one project it grew into the statewide movement to protect the rest of the coast and to encourage folks to stop and think, ‘Okay, what do we want out of this landscape? Do we want a coastline lined with sea walls and high rises and private beaches?’ You know, in California, the law now says, ‘This is a public good.’ The fight began in Sonoma County with a couple of really forward thinking people who thought about ‘What do we want to leave for future generations’ and really just took it from there.

WC: In the book’s chapter about Marin City, you quote a UC Berkeley researcher who points out that climate change will cause water to move from four different sides—“extreme rain from above,” “from river flooding” on one side, “from sea level rise” on another and “from below” due to rising groundwater. Can you talk about how Marin City and other communities will be impacted by rising groundwater?

RX: When we think of sea level rise, we think of waves crashing onto the beach and the ocean sweeping through streets and those kinds of dramatic images of just huge swells making landfall. But Kristina Hill at UC Berkeley and this growing movement of researchers have been looking into this more out of sight, out of mind aspect of sea level rise known as groundwater rise.

This is not like the groundwater that is embedded in aquifers hundreds of feet underground that we are drilling very long wells to draw from for drinking water. This is the groundwater that sits less than 10 feet below the surface. It’s the rainwater that gets soaked into the ground and forms a very shallow pool of groundwater pretty close to the surface. So if you think about it, when sea level rises, and the tide is moving in, pushing inland underground, as it’s pushing inland underground, the freshwater sits on top of the saltwater. And so, as that tide is rising, this shallow groundwater table is also rising. As it moves up, it’s getting closer and closer to breaking the surface.

This groundwater table tends to hold a lot of polluted runoff from rainstorms, the chemicals and the gross stuff on our streets that don’t make it into storm drains and don’t get treated. The question that Kristina Hill raises is ‘What about all these communities that have been stuck living next to or on top of formerly contaminated sites from industrial uses in past eras?’

The way we typically clean up a Superfund site, for example, a decommissioned chemical factory, is to cap it. You pour a layer of concrete over it and you’re like, ‘Okay, it’s no longer contaminated.’ But what happens if the groundwater underneath this cap starts remobilizing the soil and it starts moving the contamination elsewhere with the flow of water? So these are all really important questions to start asking and examining as, you know, the tides get higher and higher. And what does this remobilization mean for communities that, you know, have plumbing within the same 10 foot depths from the surface? What does it mean for communities who are living adjacent to sites that were, quote unquote, cleaned up?

There are just so many unanswered questions; however, there is a growing movement of research into this, and there are regulatory agencies now, really looking into this. However, no seawall is going to stop this rising groundwater table from potentially remobilizing so many legacy problems that we didn’t get around to cleaning up properly.

This is something that communities like Marin City and others in the San Francisco Bay Area are truly wrestling with. Think about every single formerly industrial site that got turned into something else. This is a question that affects all of us.

WC: The book isn’t all doom and gloom. Can you give our readers and preview of the final chapter, which takes us back to Sonoma County?

RX: Yeah, the movement to get the Coastal Act enshrined into law began in Sonoma County and, not to give too much away, but the book ends in Sonoma County with two examples what we could do going into the future.

What happened on the Sonoma coast in the ‘60s and ‘70s set us on this path and I was trying to find some measure of hope and a sense of inspiration for folks that reached the end of the book. I ultimately found it in Sonoma County. There was something really full circle when I got there.

The idea that we are building bridges both physically and symbolically with each other, with nature and with the ocean felt like a really meaningful way to conclude this book, although the broader story of ‘What do we do about sea level rise?’ remains ongoing. How do you end a book about an issue where we still have so much power and responsibility to write a different ending?

When I found myself back in Sonoma County, I found hope and I found inspiration and a window into what the future could look like if we start to rethink the way we’ve been doing things.

———

Xia has three scheduled appearances in Marin County next month. On Oct. 18 at 6pm, Sausalito’s Books by the Bay will host Xia in conversation with Mary Ellen Hannibal. At 4pm on Oct. 21, Point Reyes Books will hold an event at the Dance Palace (503 B St, Point Reyes Station). The next day, Oct. 22 at 4pm, Xia will have a conversation with Christina Gerhardt at Book Passage in Corte Madera.

Thank you for the great article.